バイオロギング支援基金

動物の生態調査の新手法、バイオロギングとは?

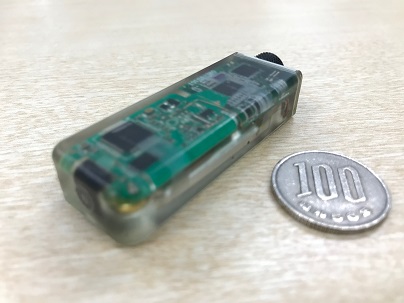

皆さんはバイオロギングという言葉を知っていますか?バイオロギングができる前は、自然の中で観察したり、動物を飼育したりすることで生態を調べようとしていました。しかし、海の中や森の中、空の上まで野生動物を追いかけていくことはできませんし、飼育されている動物は野生の状態とは違った動きをしているかもしれません。そこで、動物への負荷を配慮した小型の計測器を動物に搭載し、その計測器を回収することでデータを得て動物の自然な姿や行動を調べるバイオロギングという手法が編み出されました。バイオロギングができて以来、様々なナゾが解き明かされています。

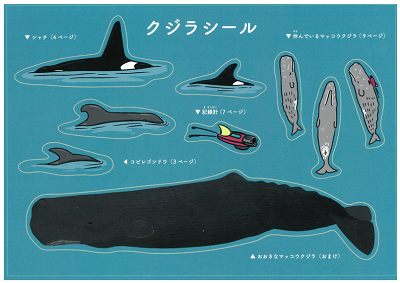

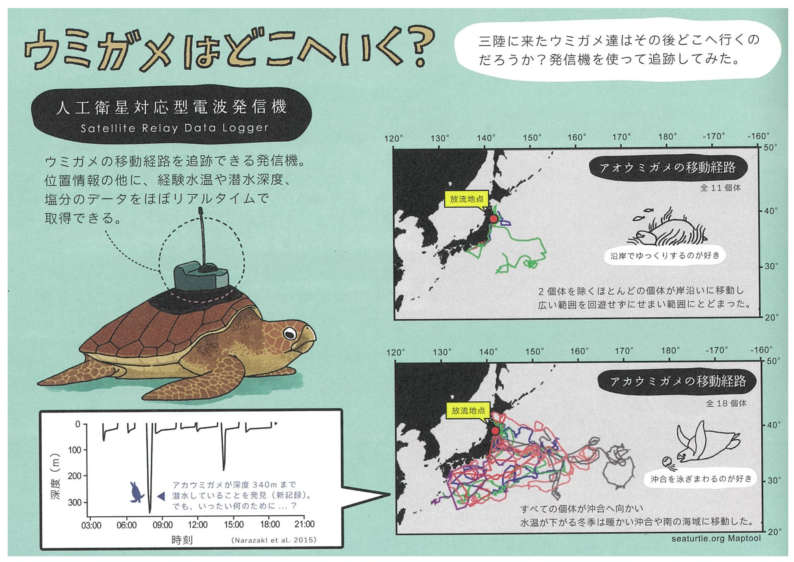

バイオロギングによる研究が進む一方で、長期的な調査の重要性が高まっています。バイオロギング研究の主な対象であるクジラ・ウミガメ・ウミドリなどは寿命が数十年と長いため、彼らの生活史を明らかにするためには長期にわたり調査を継続させる必要があります。たとえば、アカウミガメの研究では2008年に屋久島で生まれたウミガメを、なんと10年後の2018年に岩手県大槌町で発見しました。この粘り強い研究のおかげで、アカウミガメの子どもは孵化してからの10年間で甲羅の長さが60cmになるまで成長することが世界で初めてわかりました。しかし、これでもまだ子どもです。何歳になったら大人になって産卵のために砂浜に上陸するのか、何歳になったら寿命を迎えるのか、といったウミガメの一生の全貌はまだ明らかになっていません。しかし、一般的な研究資金は2~3年間であり、10年以上の長期間の野外調査を継続するのは難しい状況です。長期的かつ安定した財源が確保できないと数十年以上にわたるであろうウミガメの一生は明らかになりません。同じように、寿命が30年にもなるオオミズナギドリの夫婦の絆は何年間続き、何回くらい浮気(!)が起こるのでしょうか。あるいは、日本周辺海域のマッコウクジラはどのような経路を回遊するのでしょうか。このように、腰を据えた研究ができなければ明らかにできない生態の謎は山積みです。これらの謎に挑むためには従来の予算だけではなく、長期的に柔軟な活用ができる皆様からのご寄付が必要不可欠なのです。

バイオロギングでなにがわかるのか?

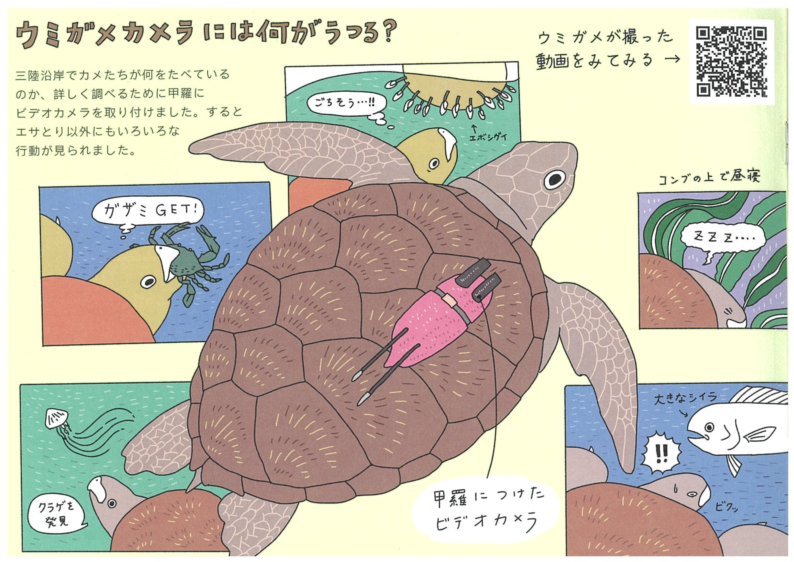

現在多くの海洋生物が絶滅の危機に瀕しています。そんな動物たちを保護するために有効な手段を講じるためには、例えば、どこで何を食べているのか、といった基礎的な生態の正しい知識が必要不可欠です。バイオロギングはこれまでわかっていなかった動物たちの様々な基礎生態を明らかにしています。それぞれの研究については、詳細なコラムを連載中です。

第1回:ウミガメは年齢不詳?

第2回:暗視カメラは捉えた!オオミズナギドリ浮気の瞬間!

第3回:データを求めてどこまでも? 怒涛のカジキ調査

第4回:カメはのろまではない

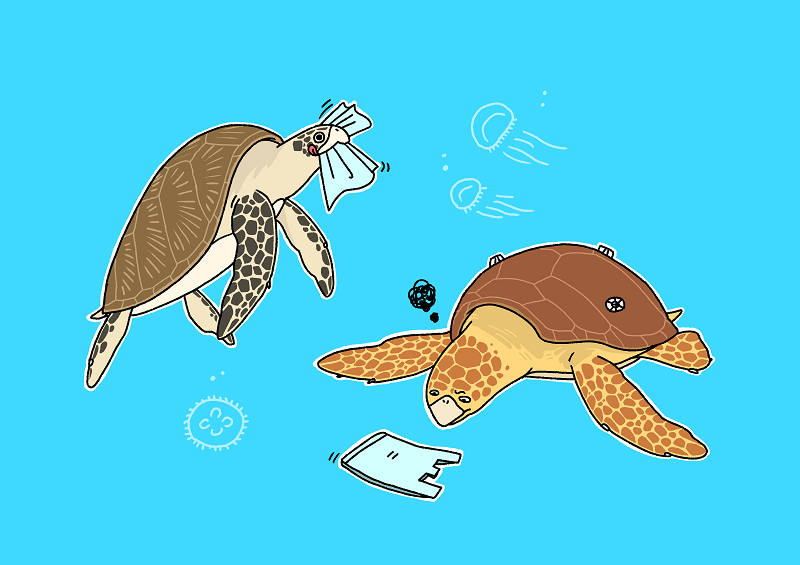

第5回:ウミガメとプラスチックゴミ

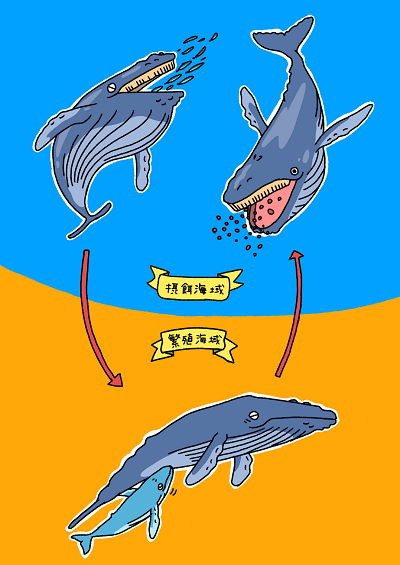

第6回:泳ぎ方から分かってしまうクジラの肥満度

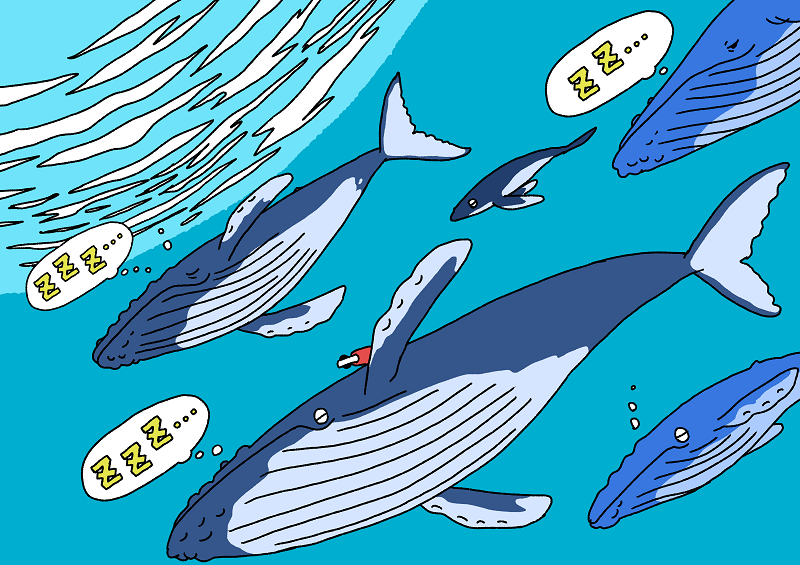

第7回:水中で仲間と一緒に休息するザトウクジラ

第8回:モニタリング用ウミガメの放流が始まりました。

第9回:みんなでウミガメの移動を見守りましょう!

第10回:大学院生、はじめてのフィールドワーク

第11回:ウミガメを求めて北へ南へ

第12回:クジラの心拍数ってどのくらい?

第13回:インド洋のエウロパ島で行ったグンカンドリ調査

ご支援のお願い

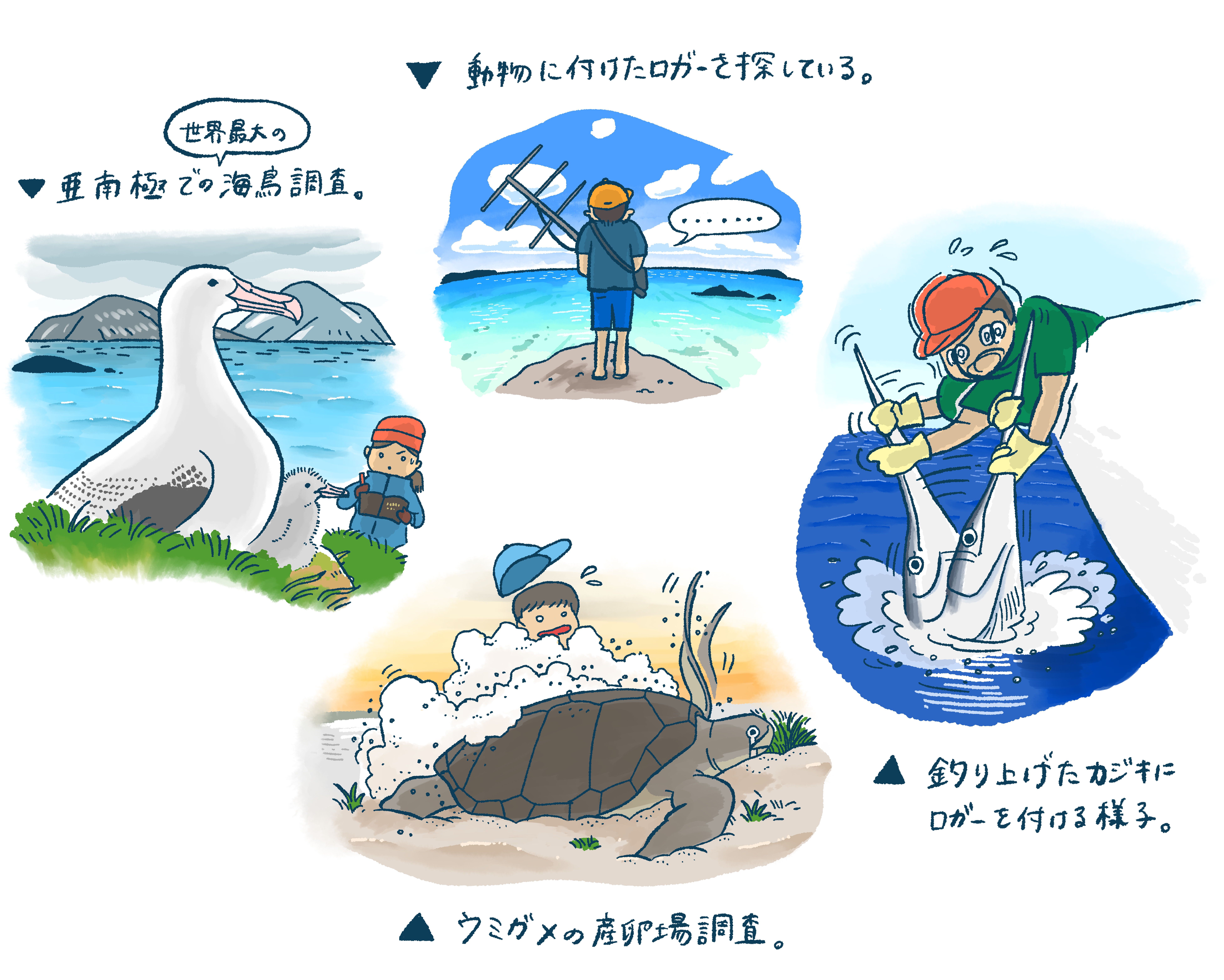

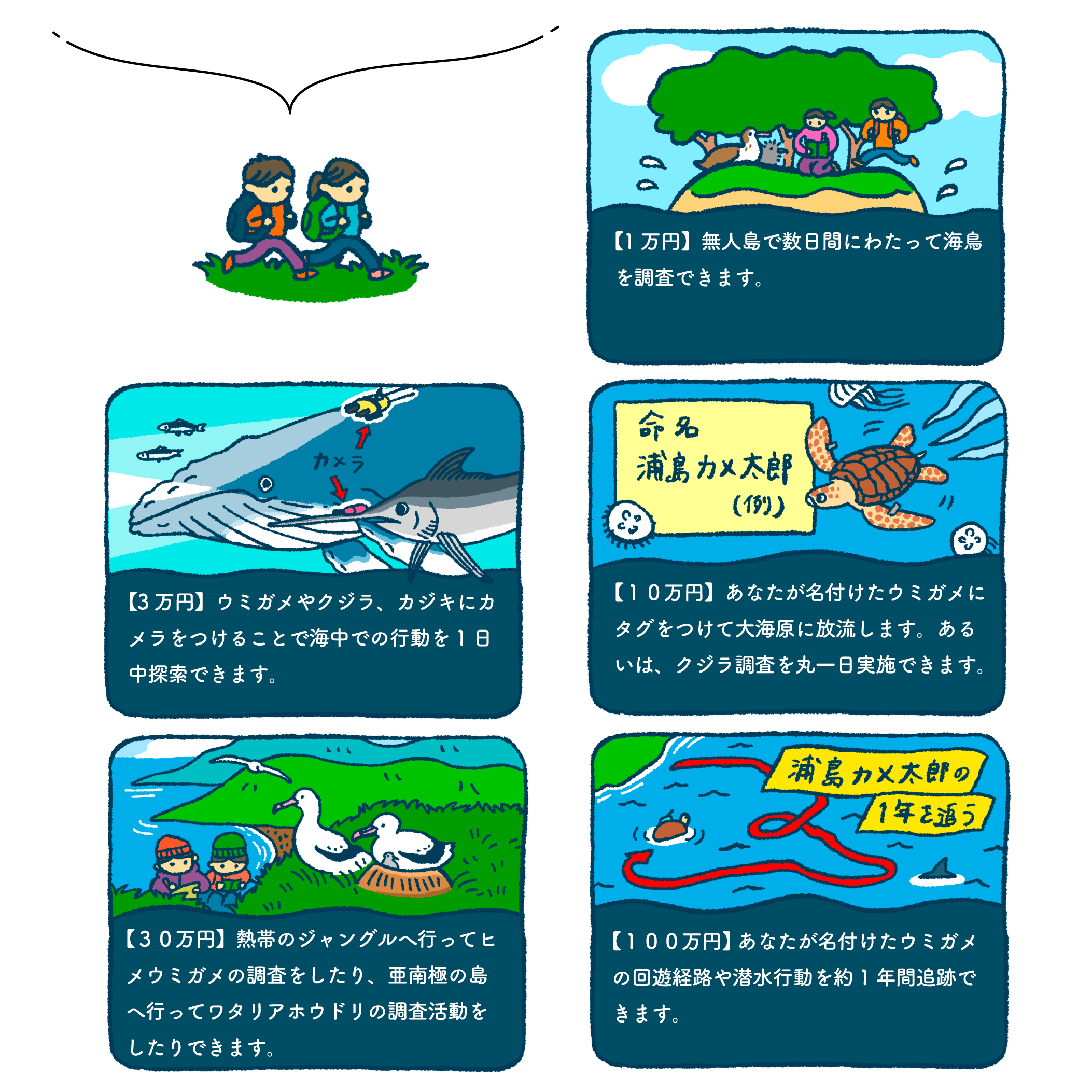

バイオロギングの活動を身近に感じていただくことができる

様々な特典をご用意いたしました

研究を発展させ、動物たちの生活を明らかにするためには長期的かつ安定した財源が必要です。あなたからのご支援により、研究者たちはこんなことができるようになります。また基金が貯まることで中長期的に研究を支える様々なことができるようになります。

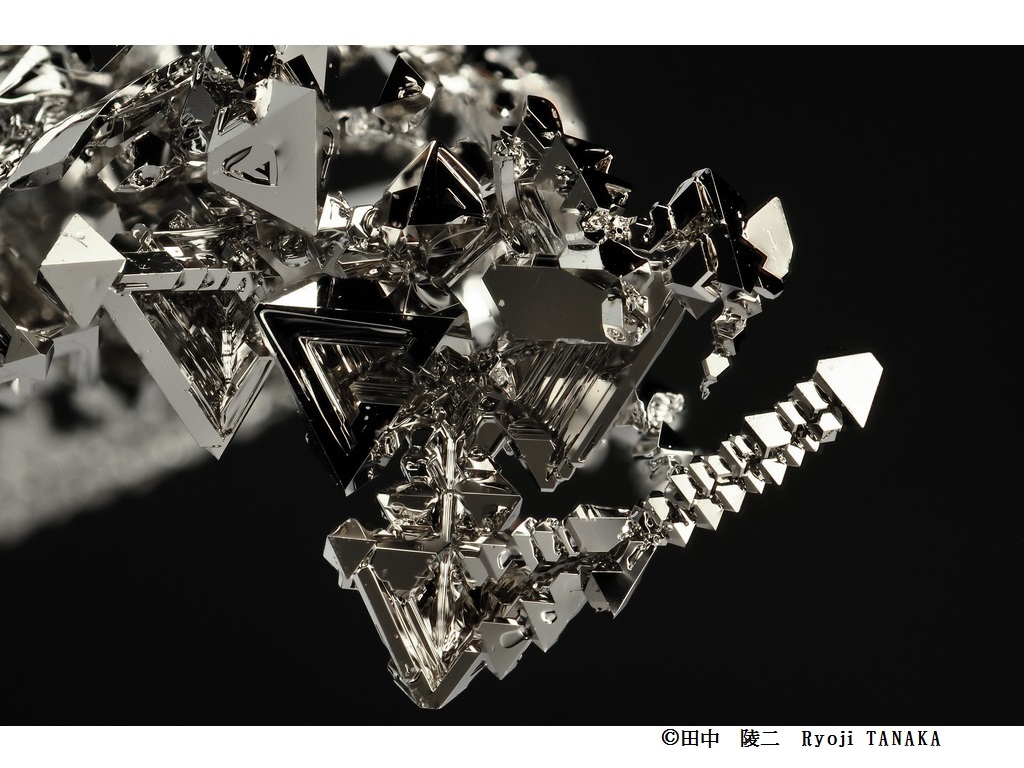

バイオロギングの歴史は測器開発の歴史でもあります。より小型で長期間の測定ができる装置、これまで得られなかった新しいデータを測定する装置の開発を常に進めています。装置の小型化により、動物への負荷もより軽減できます。

飛んでいる鳥の姿勢、位置、高度、羽ばたき頻度などを測定出来ます。

動物搭載型のカメラ第一号は、1998年にできましたが、重さが3kgあり、双眼鏡ほどの大きさがありました。

若手研究者支援

数年前に小学校や中学校の国語教科書にバイオロギングが登場し、若い世代における知名度は年々上がっています。嬉しいことにバイオロギングをやりたいといって進学してくる学生の数が年々増えています。プロのバイオロギング研究者として独り立ちする為には論文を書かねばなりません。ところが、研究成果が論文にまとまるのには普通数年を要します。特にバイオロギングではこれまでご紹介した通り息の長い研究となることが多いため、成果が出るまでの間、若手研究者の生活と研究活動を経済的に支援することが必要です。

佐藤克文教授の意気込み

定年退職した後も調査を続けます!

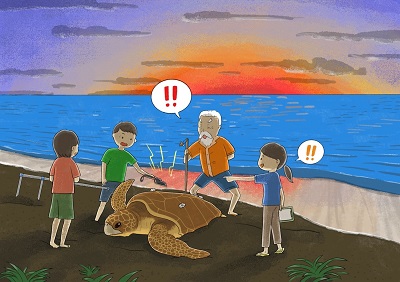

下のイラストは、バイオロギングで学位を取った木下千尋さんが描いた「教授の将来の夢」です。毎年、岩手の海でウミガメ亜成体の体内に個体識別用のタグを挿入して放流しています。放流を初めて10年が経ちますが、どこの砂浜からもまだ連絡はありません。いつかこのウミガメが大人になって、砂浜に産卵上陸するのを見届けようと思っています。

右から2人目が佐藤教授(の将来の姿)

コラム:社会への応用 "Internet of Animals" とは!?

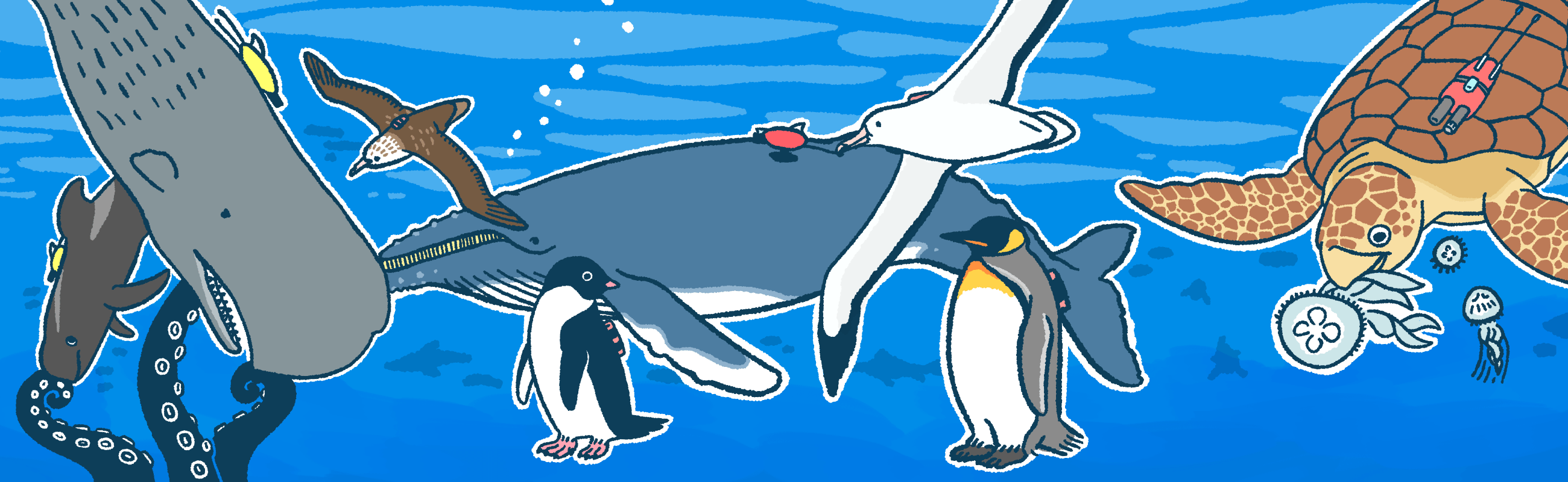

バイオロギングによって、動物から大量の情報が得られるようになってきたことを受けて、これらの情報を海洋環境の把握にも役立てることが出来るのではないかと私たちは考えるようになりました。

陸上では全てのモノがインターネットにつながる Internet of Things により、多種多様なビッグデータが生み出され、利活用されるようになりつつあります。Internet of Thingsとは、インターネットに接続されたセンサーを様々なものに搭載することで、大量の情報を収集し、世の中を良くしていこうという考え方です。ただし、現状では海洋に多くの情報収集端末を設置することは出来ていません。

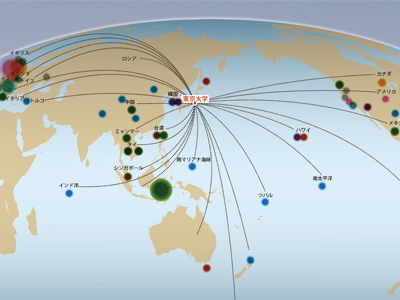

これまでの研究によって、海洋動物を使って海面下の水温や塩分に関する情報を得たり、海表面流や波浪、さらに海上風の測定が出来るといった、思いがけない成果が次々と得られています。この海洋動物由来の情報をリアルタイムでインターネットに配信できるようにすれば、情報空白地帯であった海洋からも大量の情報を収集することが可能になります。動物は日々餌を求めて自律的に動き回るので、少数の端末からでも生物生産性の高い海域に関する有用な情報を効率的に集めることが可能です。このようなことが実現すればまさに Internet of Things ならぬ Internet of Animals と言えるでしょう。従来の人工衛星や自動昇降ブイを使った観測手段と相補的なやり方で情報を集めることで、より正確に海洋環境を把握して、精度良い予想ができるようになり、台風や干ばつなど海を起点とした自然災害による被害を低減させることが出来ると考えています。

Internet of Animalsが実現した世界では

様々な動物たちがリアルタイムで海洋の貴重な情報を教えてくれています

イラスト:木下千尋

バカンス?いいえ、サメ調査です。

2025年05月02日(金)

(報告者:福岡拓也)

常夏の楽園、美しい海のリゾート、サーファーの聖地・・・

こうした言葉を聞いてみなさんが思い浮かべる場所はどこでしょうか?おそらく多くの人が同じ場所を思い浮かべているものと思います。今回はそんな所に2カ月半滞在しておこなってきたサメの野外調査について報告します。

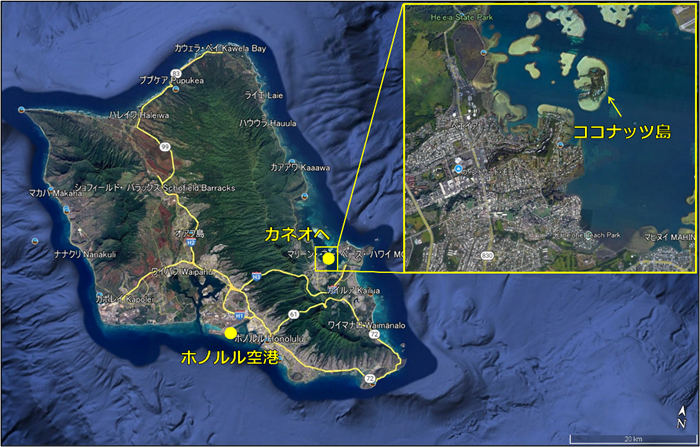

「アロハみなさま、この度はハワイアン航空をご利用くださいまして誠にありがとうございます。当機はただいま、ホノルル、ダニエル・K・イノウエ国際空港に着陸いたしました」

このアナウンスを聞いただけでなんかワクワクしてきませんか?みなさんの予想通り、今回の調査地はアメリカ50番目の州・ハワイです。日本とアメリカの中間くらいにある印象なので、5時間程度で着くものかと思っていたら、実は7時間半(帰りは9時間半)という意外と長旅の末にたどり着くのがハワイの玄関口・オアフ島です。

入国審査を終えてワイキキやホノルル市街地へと向かううらやましい浮かれた観光客を横目に、私は車で30分程度かかる島の反対側・北東部のカネオヘという町へ向かいます。そして、カネオヘ市街地近くの半島から100mほど離れたところに浮かぶ小島が今回の目的地・ココナッツ島です。このココナッツ島、島全体がハワイ大学の臨海実験所(Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology:通称HIMB)となっているのですが、名前の通りたくさん生えているココナッツの木が南国感を醸し出し、青い空に青い海があり、プライベートビーチがあり、私のような外来研究者用にオーシャンビューの宿泊施設があり、基本的に晴れで通り雨の後には虹が出るという、さながらリゾートアイランドの様相を呈していました。

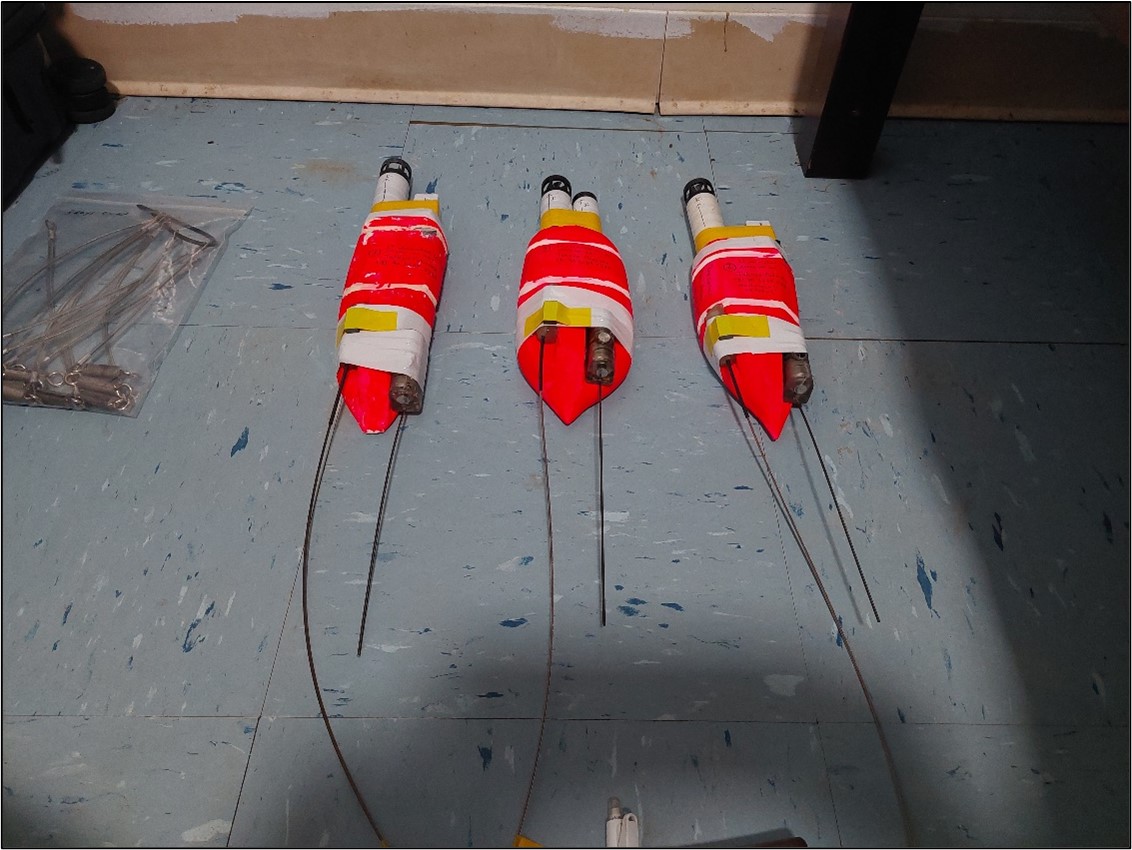

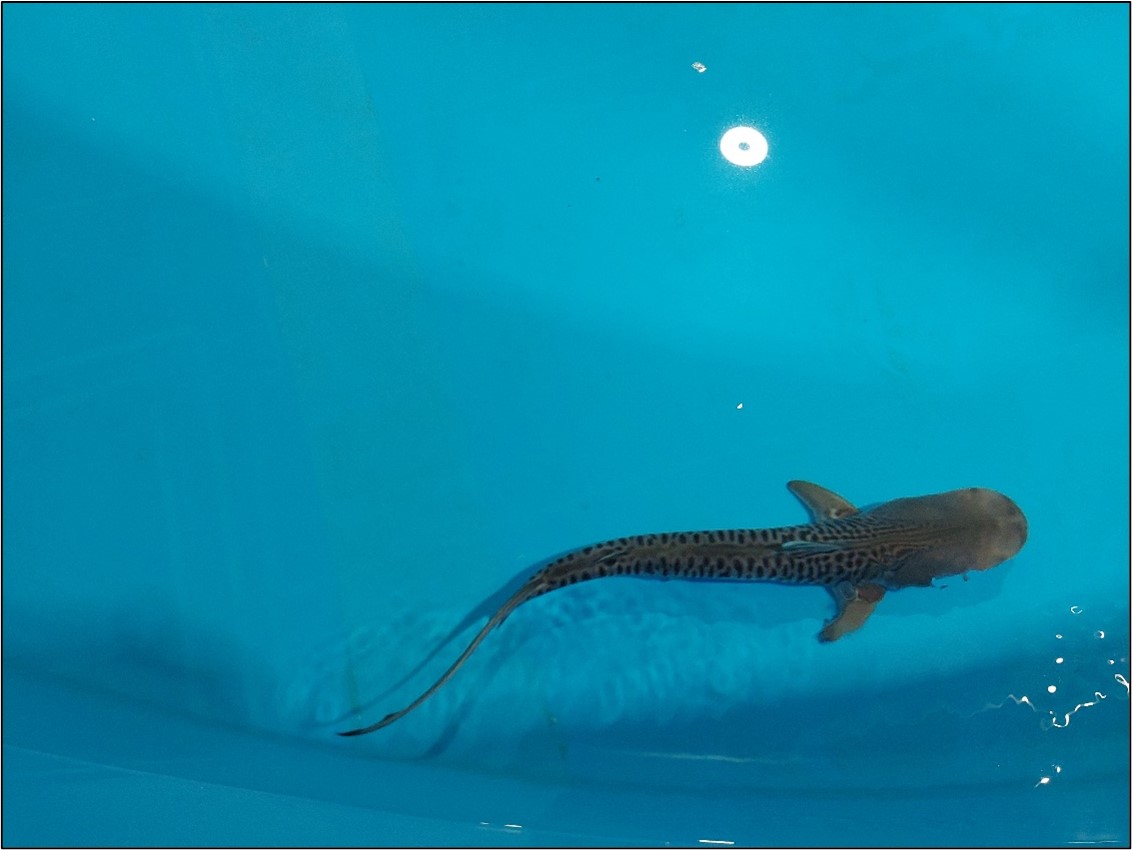

そんなHIMBでは、サンゴ礁の小さな生物から沖合のクジラまで幅広い生物の研究を行っています。今回私がお世話になったのは、その中でもサメ類や外洋性の魚類を扱うCarl Meyer博士の研究室です。これまでウミガメを対象として研究してきた私にとって、今回の調査は初めての連続でした。サメはでかい釣り針にマグロの頭をつけた延縄漁で捕獲します(サメ調査はもちろん初めて、マグロの頭を餌にする漁も初めて、手のひらよりも大きな釣り針を使うのも初めて)。

約2時間沈めた延縄を引き上げ、サメが釣れていた場合には、逃げようと暴れるサメをなんとか力で抑え込んで最後は船に横付けして仰向けにします(サメと力比べするのも初めて)。サメは仰向けになると擬死状態という硬直不動の状態になるので(注:個体差がありました)、その間に形態計測と胸ビレへの記録計の装着を行います(サメに触るのも初めて)。その後、サメをもとの姿勢に戻して放流します。

今回の私の興味は「漂流ごみに対するサメの反応」でした。というのも、ウミガメ類に取り付けたビデオ映像では種によって遭遇したごみを飲み込む確率が異なり、その種の主な餌と関連していそうという結果が得られていました。じゃあサメ類ではどうなのだろうか?幅広い食性を持つ種はごみも飲み込みやすいのか?について調べることを大目的に、まずは餌の選択性が低くごみも含めてなんでも食べることから「ヒレのついたゴミ箱」などという不名誉なあだ名もあるイタチザメを対象としてビデオカメラを装着してみました。結果として、6個体から合計45時間の映像データを得ることができました。今後映像を確認して、ごみに遭遇した時の反応を探っていきたいと考えています。

さて、今回のハワイへの滞在はもちろん調査のためですが、実はもう一つ“国内にとどまりがちな大学院生や若手研究者を海外へ送り込むための拠点づくり”という目的もありました。言葉や文化の違いも少ない慣れ親しんだ日本国内で研究をしていると、その心地よさを捨ててまで海外へ行って新たなことを始めようとはなかなか思わないものです。しかし、日本とは違う価値観やスケール感で行われる研究活動を経験することは、長い目で見ると必ずその人の強みになるはずです。

今回のハワイでも、直径10mを軽く超える実験水槽があったり、様々な大きさの調査船があってそれを運転できる技術を身に着けた学生やスタッフがたくさんいたりと、日本ではなかなか見ることのできない設備や人々の中で調査をできたことは大きな経験だったと感じています。

こうした経験をより多くの学生や若手研究者に積んでもらうことで、自分の研究の立ち位置や強み、足りない部分をより広い視野で考えることができる研究者に育っていってくれると信じていますので、これからも皆様からの暖かいご支援をいただけると幸いです。引き続きの応援の程よろしくお願いいたします。

『渚に佇む、亀というレジデンス。夜景、自然、喧騒。味わい尽くす贅沢を。』

2025年03月10日(月)

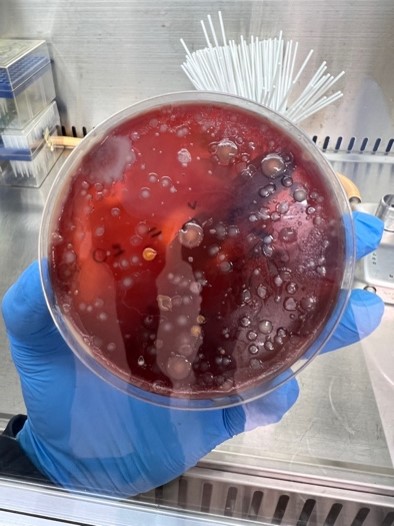

皆さんこんにちは。修士一年の菅野です。私は今年度からこの研究室でアオウミガメの採餌生態と腸内細菌について研究しています。私も他の研究室メンバーと同様、バイオロギングを使ったウミガメ研究もしますが、腸内細菌を培養するといった、いわゆる“実験”ラボワークの研究をしている人は今の所私しかいません。なので、ちょっと他の人とは違う目線から、この夏に行った沖縄での調査と実験についてお話させていただこうと思います。

「なんでウミガメの腸内細菌なんか研究するの?」と、この研究をしているとよく聞かれます。昨今の健康ブームからよく耳にするようになった腸内細菌というフレーズ。その重要性が注目されていますが、「じゃあウミガメさんに健康になってほしいんだね!」と言われると少し違います。もちろん最終目標の一つには飼育されているウミガメを健康にというのもありますが、アオウミガメの食事には大きな謎があり、私の研究の目標はそこにあります。

アオウミガメは、生まれてすぐの頃は海を漂いながら、クラゲなどを食べて成長しますが、大きくなって沿岸に定住するようになると今度はもっぱら海藻をメインに食べるようになります。しかし!アオウミガメは自分では海藻を分解できないのです。驚きですね。では、海藻しか食べないのにどうやって海藻から栄養を得ているのか、そこで微生物が頑張っているのではないかという仮説が生まれたわけです。その謎を解明するため、我々は八重山の奥地へと向かった−−。

「何もないじゃん。」 調査地である沖縄県の黒島についた最初の感想はこれでした。私たちが調査に訪れたのは沖縄県の八重山諸島の黒島です。もう少しわかりやすくいうと、沖縄の石垣島と西表島の間にある一周が約13 kmほどの小さな島です。簡単に自転車で一周できます。いかにも沖縄というような綺麗な海と、広大な草地、この島には山がなく、川もありません。ひたすら開けた島で、人より牛の方が多い。そんな島です。そしてここ黒島にあるのが黒島研究所。我々ウミガメ班がベースキャンプとする施設です。 荷物をおろしてさて実験に使う機械は…と思ったのですが、実験に必要な機械類が無い。研究所と名前がついているからには最低限の実験設備があるかと踏んでいたのですが、これがまるで無い。しかし無いものはどうしようもないし、無いなら自分でどうにかするのがこの島のルールです。郷に入っては郷に従います。工夫すればどうにかなる⋯多分⋯。

「誰か海に入れ!」 島に到着して翌日、早速やることがあります。それはカメをとってくることです。どうやって?それはもちろん海に飛び込んで捕まえるしかないです。特別な許可を取ってですが。

やり方は単純で、見張り役が高いところから海を見渡してカメを見つけます。見つけたら、網を張る役がこっそり海に入って、気付かれないようにカメのまわりを大きな網で囲いを作り、出られなくなったところを捕まえるといった具合です。この島の周りにはアオウミガメが定住していて、機械に困ることはあってもカメに困ることはありません。我々ウミガメ班は、網で囲っている間にカメが逃げないか見張っている役でしたが、海で網を張る役の研究所職員の方から「誰か一人海に入れ」の指示が。ふと、チームメンバーの服装を見てみると海に入るなんてまるで想定していなかった格好で、海に入れそうなのは自分だけ。「(⋯えっ、俺じゃんw)」。入りました。

とりあえず職員の方のもとへ泳いで行くと、いきなり「はい。落とさないでね。」とアオウミガメ。実物のウミガメを初めて見た感動とか、触った感覚とかを感じる暇もなくひょいと渡されました。最初の感想はキレイとか可愛いとかではなく「重ッ⋯!」でした。しかも陸まで運ぼうにも、海の中では明らかにカメに分があります。とにかく力は強いし暴れるし。カメも必死かもしれませんがこっちも必死でした。

「そんなのどうすんの?」 カメをとってきてクタクタですが、ここからが実験です。何とまだスタートライン。調査って大変ですね。 私の実験はまず “待ち” から始まります。

Q。 何を?

A。 糞をです。

「そんなのどうすんだ」という話ですが、腸内細菌をとるならこれが一番早いし楽なんです。糞はついさっきまで腸内にあったものですから、微生物の塊です。絶好の実験材料になります。そしてここからも大変。まず、陸にいる動物と違ってウミガメは水中にいます。時間が経てば、糞はふやけて使い物にならなくなります。待ってりゃいつか出てきますが、いつするかはわからない。だから30分ぐらいおきに昼夜水槽を巡回する必要があったんですね。そして次にいわゆる腸内細菌と呼ばれる細菌は酸素に触れると死んでしまいます。すぐ死にます。なので、実験操作は細心の注意を払い、なおかつ早急に操作を行う必要があります。もっともそこが腕の見せ所なのですが。今回の私の黒島調査の一番の目的はここ黒島で初期培養を行うことだったので、慣れない環境での慣れない作業でしたが、とにかく気合いでやりました。今回の調査ではこれを計4個体分繰り返したら,沖縄でやることはここまで。分離の最初の段階は現地で行いますが,続きは実験室内でやります。

プロは匂いでどんな菌がいるかわかるらしい。

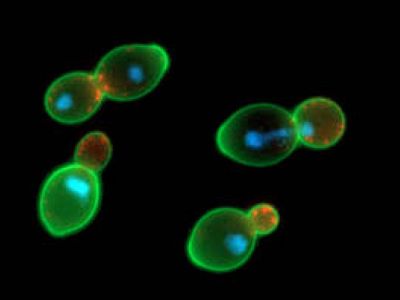

「カメにはカメの乳酸菌?」 文明にただいまを言ったところで、ここからはラボでの作業になります。その後はとってきた細菌の種を大まかに特定するためにDNAを抽出して分析する作業があります。

黒島の現地で培養したものを見てみるとこんな感じ。シャーレ一面に広がるコロニー。この中には同じ菌のコロニーがいくつもあれば、違う菌が作ったコロニーもあります。まず必要なのが、これを仕分けるという間違い探しです。

超高難易度間違い探しが終わると今度は一つ一つのコロニーを増やす作業があります。これもなかなか骨が折れる。というのも、微生物実験の大変なところの一つが培養に時間がかかるというところです。つまり、一概に私が頑張れば、その分早く終わるわけではないのも辛いところ。黒島の微生物サンプルは200弱の数があったので、丸々3日は朝から終電くらいまで作業といった生活を送ってました。

取ってきた菌の中にはいろんなものがいて、有名どころでいうと乳酸菌なんかもいます。(病原菌もいますが⋯)「カメにも乳酸菌っているんだ」と言われたこともあります。いわば私の研究はカメ特有の細菌を探す研究でもあるので、「カメにはカメの乳酸菌」ということですかね。実は乳酸菌っていろんなところにいて、腸だけでなく海やその辺の土壌なんかにもいます。思ってるよりも微生物はそこら中にいるんです。 他にも面白そうな菌はたくさんいたので、今後はこいつらも使って実験もしていこうと思います。

現在、黒島に加えて岩手県の大槌町でも同じような実験を行い、結果を見て毎日頭を抱えています。果たしてこの中にアオウミガメの海藻の消化に関わっている菌はいるのか?結果が出たらまた報告します。

ウミガメの放流実験だけでなく、こんな実験ができるのも皆様の温かい支援のおかげです。心より感謝申し上げます。それでは。

2024年活動報告

2025年01月21日(火)

今年は3月にバイオロギング国際シンポジウムを東京大学で開催することが出来ました。2003年に東京で第1回国際シンポジウムを開催する際に、バイオロギングBio-Loggingという言葉が提案されました。その後、3年毎に世界各地で国際シンポジウムが開催されるようになり、21年後に再び日本で第8回大会が開催されたというわけです。シンポジウム期間中に高校生・大学生向け講演会を開催し、大学に所属する研究者とNASAの宇宙飛行士に魅力的な講演を行ってもらいました。

皆様のサポートもいただいて、岩手県・山口県・茨城県といった国内各所、さらにカナダやハワイにおける野外調査を遂行することができました。各種野外調査で得られたデータは、現在博士研究員や大学院生達がとりまとめ中です。7月の活動報告でお伝えしたとおり、昨年は、博士研究員の上坂怜生さんがインド洋亜南極圏にあるケルゲレン島にいってキングペンギン調査を行ってきました。今年も再びインド洋亜南極圏にあるクロゼ諸島に渡りアホウドリ調査に行く予定だったのですが、現地で鳥インフルエンザが蔓延し、残念ながら野外調査は中止となってしまいました。2024年に公表された論文の中では、当研究室の卒業生であり現在名古屋大学に所属する後藤佑介准教授が記した論文、Albatrosses employ orientation and routing strategies similar to yacht racers(アホウドリはヨットレーサーと同様の定位と経路選択戦略を採用している)はアメリカ科学アカデミー紀要に掲載され(doi: 10.1073/pnas.2312851121)、マスメディアでも取り上げられて話題となりました。

例年通りバイオロギングカレンダーを作成し、継続支援をして下さった方と3万円以上のご寄付をいただいた方へ年末にお送りしたところです。

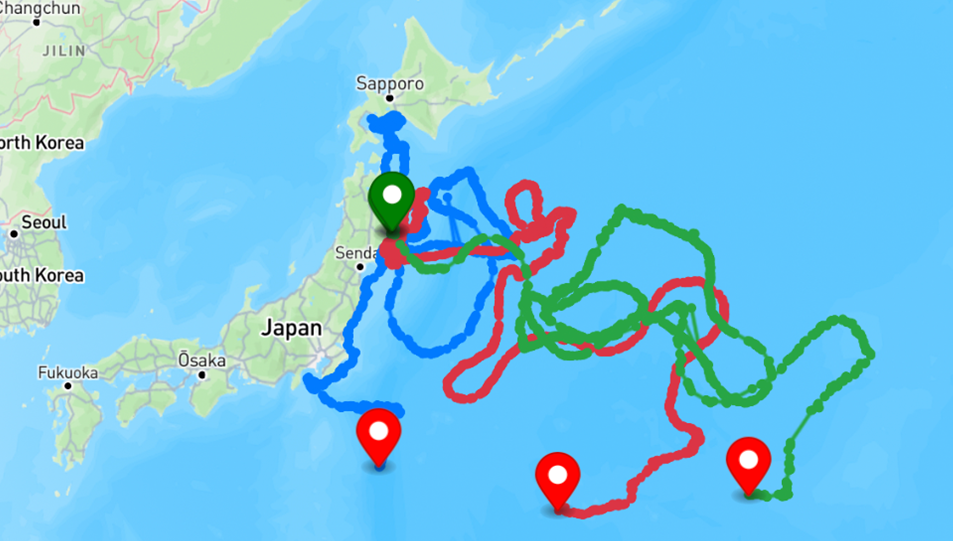

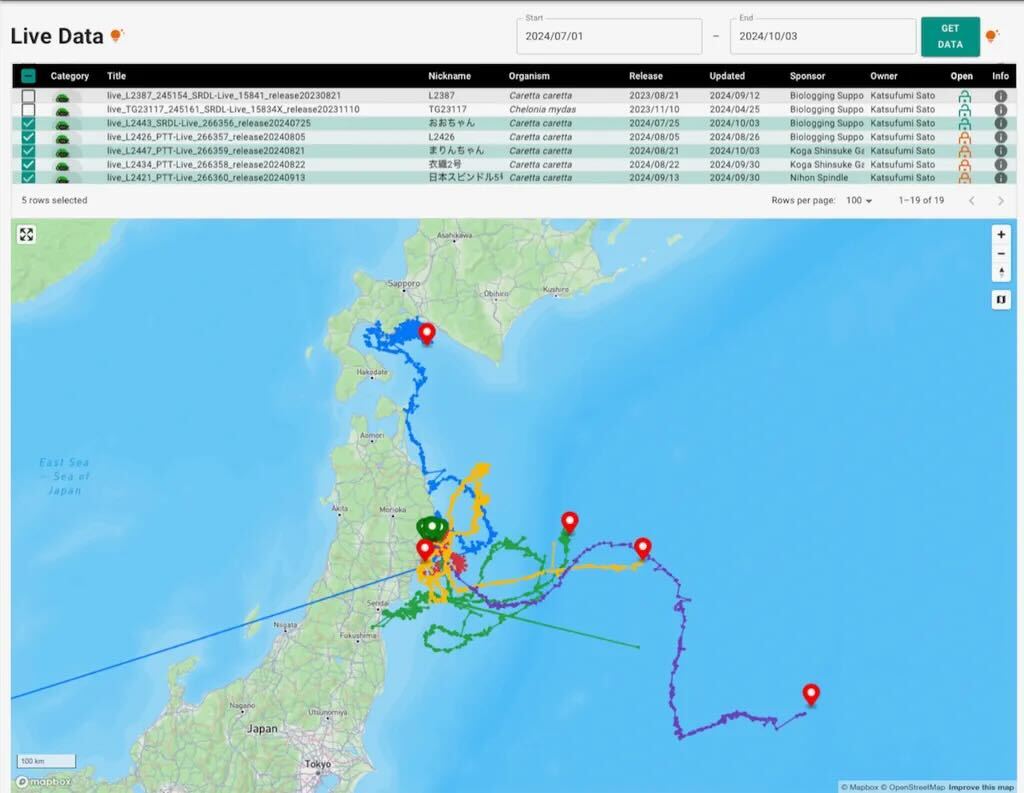

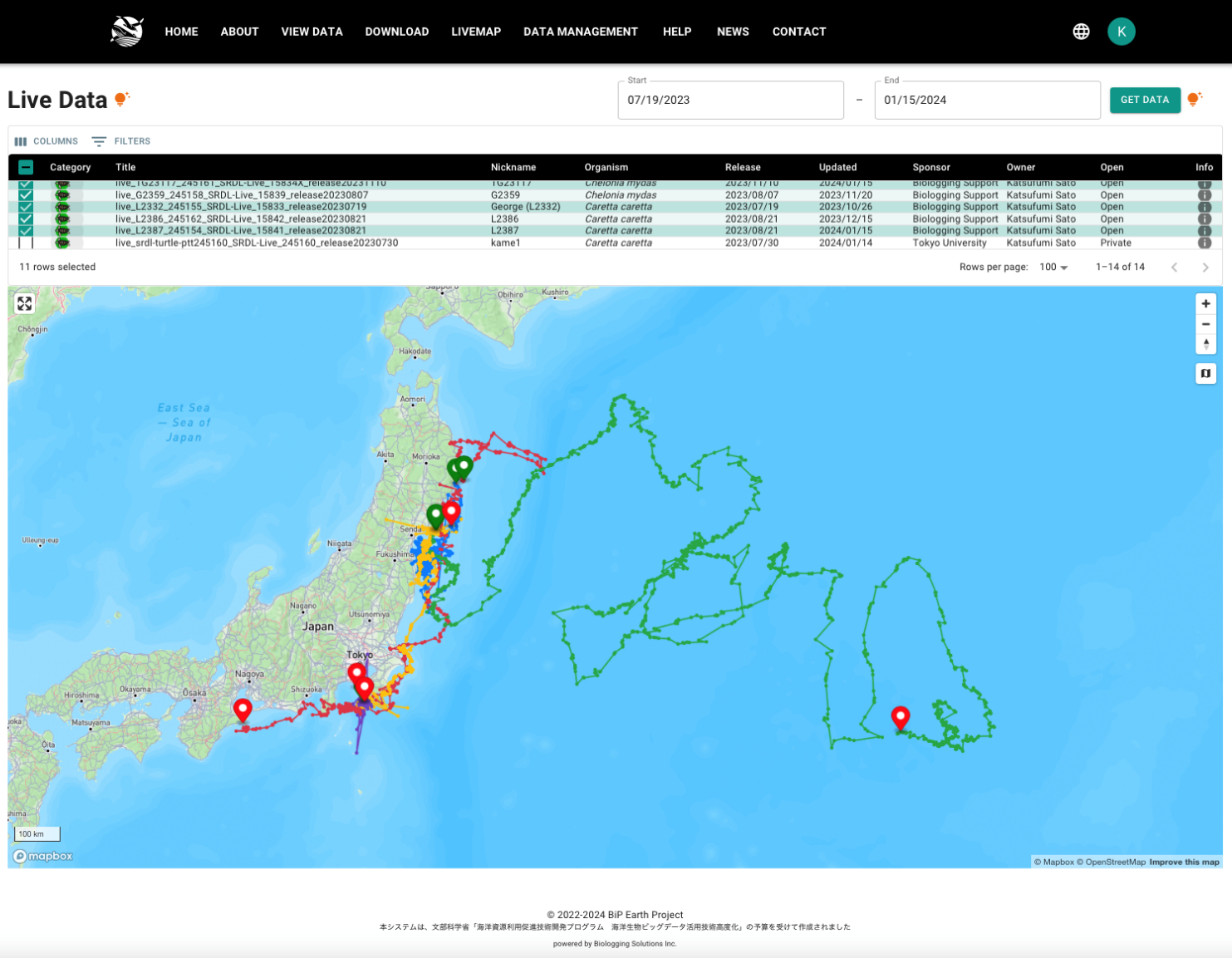

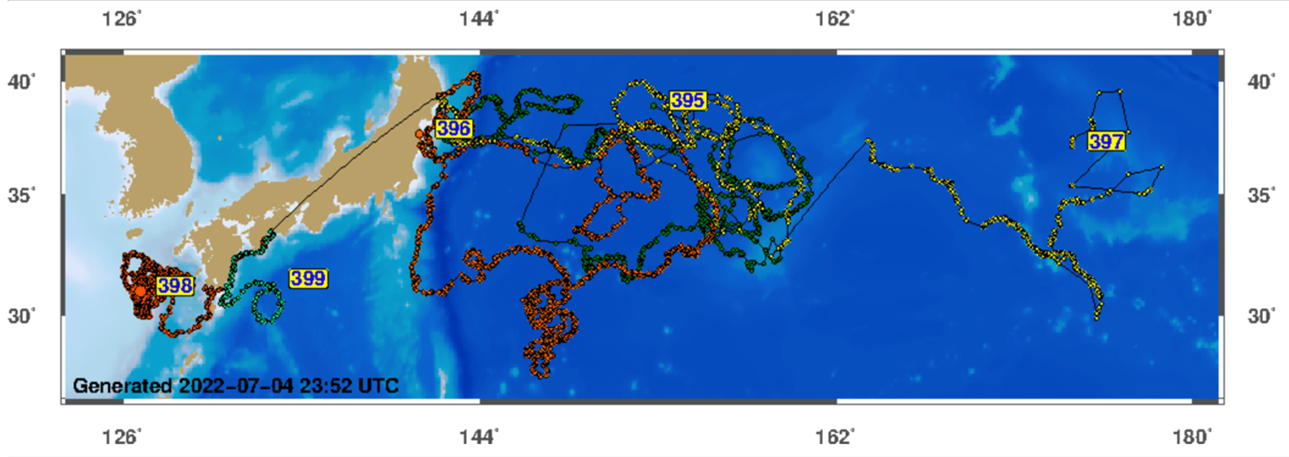

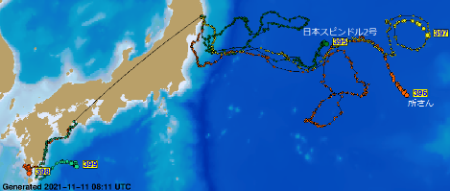

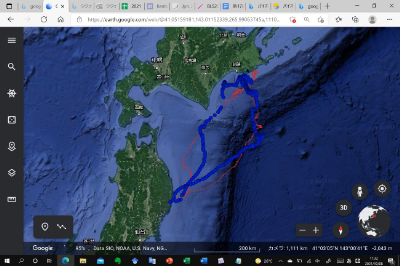

2024年の夏に、アカウミガメ5頭に人工衛星発信器をつけて、岩手県釜石市から放流しました。L2426と名付けられた個体は放流後1ヶ月ほどで通信が途絶えてしまいました。マリンちゃんと名付けられた個体は、11月末で通信が途絶えました。その他の3頭(おおちゃん、衣織2号、日本スピンドル5号)はまだ通信が継続しています。上の図には3頭の経路を乗せていますが、いずれもだいぶ南下しています。

以下のページからどなたでもウミガメの経路を眺めることが可能です。引き続きこの3頭の行く末を見守って下さい。

Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP)のサイトはこちら

①LIVEMAPボタンを押す

②ページの上には一覧表があり、個体データが並んでいます。自分が見たい個体を左端のカラムでマークを付けます(複数個体選択可能)。

③「GET DATA」ボタンを押すと個体の経路が地図上に現れます。

Treasure Maps and (Not Quite) Mermaids: Pitted Stingray Biologging Adventures from the Seto Inland Sea

宝の地図と人魚(らしい生き物):瀬戸内海ホシエイのバイオロギング冒険

2024年12月04日(水)

This fall, I returned to Kaminoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture for research. Although I have been fortunate enough to conduct surveys in the area several times now, each time the bags of research gear and data loggers are packed, I feel nervous and excited at the same time. I think that the unpredictability of the sea condition and biologging is both one of the stresses and joys of this kind of research. Although my nervousness was initially higher setting out from Kashiwa, by the time I arrived in Kaminoseki, any nerves had been greatly eclipsed by excitement and anticipation.

この秋、私は山口県の上関町に調査のために戻りました。これまで何度かこの場所で調査を行う機会に恵まれていますが、調査機材やデータ・ロガーをバッグに詰めるたびに、毎回緊張感と興奮が同時に感じられます。海の状態とバイオロギング調査の予測不可能さは、研究のストレスでもあり喜びでもあります。柏を出発する時は緊張感の方が勝っていましたが、上関に着いたら、緊張は興奮と期待ですっかり打ち消されてました。

It turned out to be quite an exciting time indeed, with many new lessons learned and valuable data gathered thanks to the team effort of local fishermen and researchers.

地元の漁師さんと研究者のチームワークのおかげで、多くの新しい教訓と貴重なデータが得られて、実に刺激的な時間過ごすことができました。

This was the first time we tried deploying data loggers on pitted stingrays for more than a few days’ deployment; loggers may become more difficult to recover with passing time and the further their host animals travel, however, longer sets of valuable data may be obtained this way. Thankfully, both logger packages we deployed safely popped up, and we assumed would be easily retrieved (using a receiver, a device with an antenna for detecting the signals sent out by data loggers), as they were quite close by. One was retrieved as usual by boat from the ocean, however, the other mysteriously could not be found, despite signals coming from it.

今回は初めて数日以上の長期間にわたってロガーをホシエイに装着しました。装着日間が長くなるほど、エイが遠くまで泳ぎ、ロガー回収が難しくなる可能性はありますが、長期間のデータが得られます。アンテナ付きの受信器を使って、浮上した装置からの電波を受信するのですが、幸いにも、装着したロガーは

2台とも無事予定通りに浮上し、浮かんだ場所までの距離がそれほど遠くなかったため、簡単に回収出来ると考えていました。1台のロガーはいつものように船で海から回収出来ましたが、もう1つは電波は受信できるのに、何故か見つけられませんでした。

In what turned out to be a multi-day search, via car, boat, and on foot, it was pieced together that the logger was somewhere on a beach. This beach was covered in various debris, which made the search process even more difficult, but thankfully challenged me to adapt and adopt additional search methods per the kind recommendations of others. On this small stretch of beach, a new type of antenna made its debut (smaller than the large antenna we use on boats, but also more sensitive and useful at close range). So also did my graceful skills in scurrying about the litter-strewn understory and climbing into the lower branches of trees with receiver in hand, and in visualizing maps of the area being searched while warding off mosquitos. It was rather ironic to be looking in a woods for a tag that had been attached to a marine fish, but I suppose that this is part of the beauty and adventure (and perhaps comedy) of biologging research. Unfortunately, I was unable to find the tag, though thanks to the efforts of many kind people’s patient assistance in the tag hunt, the search area had been significantly narrowed down.

数日にわたって、車・船・徒歩で捜索した結果、とあるビーチのどこかにロガーがあることが分かりました。こちらのビーチはさまざまなゴミに覆われていて、探索はさらに難しくなりましたが、ある人の親切なアドバイスに従って、新しい探索方法を採用しました。いつもの船から回収する際に使っているアンテナと違って、近距離の感度が高い小型のアンテナを採用したのです。ゴミが散らかっている藪の中を駆け回ったり、受信器片手に木登りをしたり、蚊をおいはらいながら探索エリアの地図を頭の中に思い描いたりといった洗練された技術も発揮できるようになりました。海水魚に装着したロガーを森の中で探すのは少し妙な感じでしたが、これこそバイオロギング研究の醍醐味(もしかしたらコメディー?)というものです。残念ながら、ロガーは見つけられませんでしたが、皆さんの協力のおかげで探索範囲を大幅に絞り込むことができました。

While contemplating on what to do next back at the main port, I received a voicemail from a person who had amazingly found the tag on the very beach we had been searching for it on. I happily dashed off towards the Hiroshima area, and anxiously but diligently waited at the station where the exchange would occur (actually a lie, as I wandered off to a convenience store nearby for reprovisioning, took photos of rice paddies, and admired two very large catfish in a storefront tank before returning to the station, as in my crazed excitement I had arrived ridiculously early). After receiving the data logger package from the person who had graciously called, I finally headed back to Kashiwa with all data loggers safely in tow. On the shinkansen, I excitedly scribbled a new (but still with questionable artistic skills) map with a star showing where the treasure had been found. The person who had spotted it had kindly informed me that it had been amongst some large rocks, which likely explained why it had been so difficult to pinpoint the signals coming from the tag, as they may have been disrupted by the rocks. In some ways, drawing the map made one feel like a pirate of sorts searching for long-lost treasure, with the value lying not in gold, but in useful data.

いつもの港に戻り、「さて、どうしようか?」と考えていたら、私たちが探索していたまさにその砂浜でロガーを見つけたという方からの着信が有りました。大喜びで広島に駆けつけ、緊張しつつ約束していた駅で待ちました(というのは嘘で、テンションが高すぎて駅に着くのが早すぎて、ウロウロと近くにあるコンビニまでいって再補給をし、田んぼの写真を撮り、ある店先の水槽にいた2尾のとても大きな鯰を眺めてから駅へ帰りました)。親切にお電話下さった方からロガーを受けとって、データ・ロガーと共に柏に向かいました。新幹線の中で私は興奮しながら(ちょっと怪しい?)芸術的技量で地図を書き、宝物が見つけられた場所に星印をつけました。発見した人曰く、ロガーは大きな石の間にあったそうです。ロガーからの電波の受信を石が妨害したため、ロガーの方向が上手く分からなかったのだと思いました。地図を書きながら、まるで自分が宝探しをする海賊であるかのように感じました。もっとも、大切なのは黄金では無くデータなのですが。

The feeling of being in some sort of adventurous tale continued with the examination of video logger footage back in Kashiwa. As I looked at beds of seaweeds and schools of fishes flitting around above the rocks, I was fondly reminded of tales of mermaids and underwater fantasies I had read about in picture books as a little kid. However, what did swim by in front of the video logger-carrying pitted stingray was no mermaid, but the undulating side profile and glowing eye of another stingray. However, I reasoned to myself that if sailors in the past mistook manatees for mermaids, then a stingray was also a fair candidate for being an almost-mermaid. Although it was likely not another pitted stingray but a red stingray (a smaller relative), it was still an interesting encounter. Specifically, it demonstrated how data and video loggers can provide information beyond simply their host organism, such as by providing clues into the overlap in space use between different species. Beyond insights into the potential ecological relationships between different species, the data collected also provides information on the environment in which the organism resides, and in this way, can be a valuable tool for piecing together the marine ecosystems, as well as the interactions between their denizens and human society as well. The collaborative efforts fishermen and researchers involved in combination with biologging are allowing previously uncollected data to be gathered, and I am looking forward to seeing what treasures we will uncover in the future.

冒険物語の中にいるような気分は、柏に帰ってビデオ・ロガーのビデオを見ている間も続きました。海底に茂る海藻やあちらこちらの石の上で泳ぐ魚の群れを眺めながら、小さい時に読んだ人魚と水中のファンタジーの物語を思い出しました。しかしながら、ビデオ・ロガーを付けたホシエイの前に泳ぎすぎたのは人魚ではなく、他のエイのうねる横顔と光る目でした。昔の船乗りがマナティを人魚と間違えたのだから、アカエイだって人魚に間違えられてもおかしくないでしょう。おそらく、それはホシエイではなくより小型のアカエイだったと思いますが、これはこれで1つの面白い出会いでした。特に、バイオロギング装置が、それが付けられている動物についての情報以外にも、例えば、別種の動物が利用する空間との重なり具合も分かるというのは重要です。別種との生態的な相互関係だけでなく、ロガーが記録するデータは動物が住んでいる環境の情報も含んでいるので、海洋生態系や、海洋生物と人間社会の相互作用を理解するのにも役立ちます。今まで集めてなかったデータを、漁業者と研究者が協力しながらバイオロギングをつかって集めていくことで、今後どのような宝物が見つかるのか楽しみにしています。

ロガーを追ってどこまでも

2024年11月05日(火)

初めまして、修士1年の小山初菜です。

ウミガメの回遊や行動などの研究をしています。

この夏、石垣島の離島黒島(5/23~6/27)と岩手県大槌町(7/11~9/25)に長期フィールド調査に行ってきました。行動生態計測グループのウミガメ班は夏三カ月の大槌調査が一般的で、新入生が大槌の前に別のフィールドに出ること自体珍しいようです(先輩談)。今回はそんなイレギュラー調査ならではのエピソードを1つご紹介したいと思います。

アオウミガメはクルクルするか?

先行研究によると、産卵期のウミガメは人為的に沖から放流されても産卵する浜に戻ってきますが、その間に旋回行動(クルクル行動)が見られることが明らかとなっています。このクルクル行動についてまだその理由は明らかとなっていませんが、自らの位置を探るナビゲーション機能との関連が考えられています。

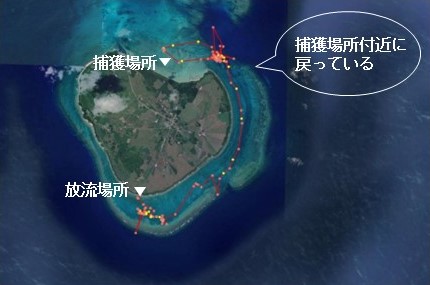

黒島のアオウミガメは島周辺の特定の場所に対する定住性が強く、例えば島の反対側から放しても元の場所に戻ってくることが知られています。

船で沖まで連れて行ったらどうやって帰ってくるのか?クルクル行動が見られるのでは?という仮説を検証するために、計2頭のアオウミガメにGPS・3軸地磁気・ビデオカメラを付けて船で輸送、放流する実験を行いました。

ロガーを追ってどこまでも

1個体目のロガーは予定通り回収できたものの、2個体目は予定時刻になっても発信がないまま黒島での調査期間が終了しました。黒島周辺はサンゴ礁が発達しているため、ロガーがひっかかり浮かないこともあります。2回目の実験で早速ロストか(ロガーが回収できないこと)…と思いつつ、「そのうち海が荒れたら浮いてくるよ」という先輩の言葉を信じて、6月27日に柏に戻りました。

7月11日、今度は岩手県大槌町へ。柏から東北新幹線、釜石線と電車を乗り継ぐこと8時間、大槌沿岸センター宿舎に到着。

いよいよメインのフィールド調査が始まる、と思いきや大槌2日目の7月12日深夜ここで事件が起きたのでした…。

「(黒島の)ロガー浮いたよ!(小声)」

大槌の朝は早いので(定置網にウミガメが混獲されると朝4時~5時ごろに漁師さんから電話がくる)、22時にはすでに布団の中にいた私。この一言で飛び起きて、PCで発信機の位置を確認すると確かに浮いている…!

やった!!と思う反面、なぜ今??と思ってしまう。素直に喜べない複雑な胸中。

- 理由①:大槌に来てまだ1日(大槌調査モードで荷物広げた矢先…)

- 理由②:明日、放流実験(大槌がメインの実験なのに…)

- 理由③:明日から「海の日」の三連休(石垣島は観光地)

- 理由④:一緒に大槌に滞在していた先生方がちょうど柏に帰った(すぐに相談できない)

「ウミガメは空気を読まない」(行動生態カメ班語録)とはまさにこのことだと思いつつ、ベテランの先輩たち数人と深夜に相談した結果、

7月13日:早朝に先生に報告→繋がらなくても石垣島に向けて出発、道中返信を待つ(回収ダメとはならないだろうから)

7月14日:石垣島で傭船してロガー回収

7月15日:大槌に帰る

という石垣島3日間弾丸ツアーへ。旅行の家族連れに混じり、どこからどう見ても観光旅行のようにしか見えない女子大学院生2人。現実はどんどん沖へと流されるロガーを必死で追いかけており、心中全く穏やかではないフライト。

翌朝8時に船を出してくださる漁師さんに挨拶をして出港。海上ではダイビングをしている一行に「あの子たちいったい何をしているんだろう???」と訝しげに見られながら流されるロガーを追いかけること2時間半、微妙に沈みかけているロガーを発見、間一髪で回収できました。充実感と疲労でその日はぐっすり眠り、翌朝再び空の上に。夜には大槌の宿舎に到着して、怒涛のロガー回収石垣ツアーは幕を閉じました。

回らない黒島のアオと回る大槌のアカ

さて、肝心のデータはどうなっていたのか??

…5日間の記録を取る予定が放流1日目でなぜかロガーがカメから外れていた、という結果に終わりました。

また、1回目・2回目両方のデータを合わせてもクルクル行動らしきものはほとんどありませんでした。

非常にモヤモヤする結果に終わり、なかなか上手くいかないなあ、と野外実験の難しさを実感しました。

ところが、気まぐれに解析してみた大槌のアカウミガメはあちらこちらでクルクルしていることが判明。

「大槌のアカウミガメは回遊性で特定の目的地がないので、クルクルしない」と想定していた中で予想を裏切る結果となりました。

回ると思っていた黒島のアオウミガメは回らず、いったい何を手掛かりに帰るのか?

回らないと思っていた大槌のアカウミガメは回り、いったい何のためにクルクルするのか?

謎が謎を呼ぶ今年の黒島・大槌調査(計4カ月)でした。

今年の調査移動総距離:約9,580 km ≒ 日本列島縦断(約3,000km)×3

これだけの大移動ができるのも皆様の温かいご支援のお陰です。

ありがとうございます。

そしてこれからも応援どうぞよろしくお願いいたします。

ウミガメ調査 無事終了

2024年10月03日(木)

岩手県大槌町において、7月から3ヶ月間にわたって行われたウミガメ調査が終了しました。総勢10名ほどの大学院生たちが、共同生活をしながら精力的に各種調査・実験を進めました。研究以外にも、地元の中高生相手のアウトリーチや、テレビの取材対応など、色々ありました。学生が運転する軽トラックにシカが激突するなどといったアクシデントもありましたが、幸いけが人や病人が出ることもなく、全員楽しく調査を終えて、無事柏に戻ってきました。

この夏放映されたテレビ番組

・2024年8月30日 ミヤギテレビ放送「うみのチカラ」

12分間ほどの番組中で、特任研究員の福岡拓也が出演し、研究紹介を行っています。バイオロギングデータベースBiPも紹介されました。

・2024年9月5日 NHK宮城News Web

8分間の番組中で、大学院生たちが研究する様子が紹介されました。とても面白いので、是非ご覧下さい。

今年、人工衛星発信器付きのアカウミガメを5頭放流しました。その経路をリアルタイムで見ていただくことが可能です。以下にそのやり方を示しますので、カメの行く末を是非とも皆さんで見届けて下さい。

・「bip-earth」で検索し、BiPのウェブサイトに行ってください。

・「LIVE MAP」ボタンを押します

ページの上には一覧表があり、個体データが並んでいます。表は上下にスクロールできます。自分が見たい個体を選び、左端のカラムでマークを付けます(複数選択可能)。

その後右上にstartとendの日付を入力する箇所があるので、ここに例えば「2024/10/03」などと「今日の日付」を入力し「GET DATA」ボタンを押すと個体の経路が地図上に現れます。

一覧表のUpdatedの欄にある日付が最後の位置情報受信日となります。最近の受信があれば、まだウミガメは大海原を泳ぎ続けているということになります。

私たちの野外調査を継続するにあたり、バイオロギング支援基金へのご寄付はとても役立っています。引き続き、皆様からのご支援をお待ちしております。

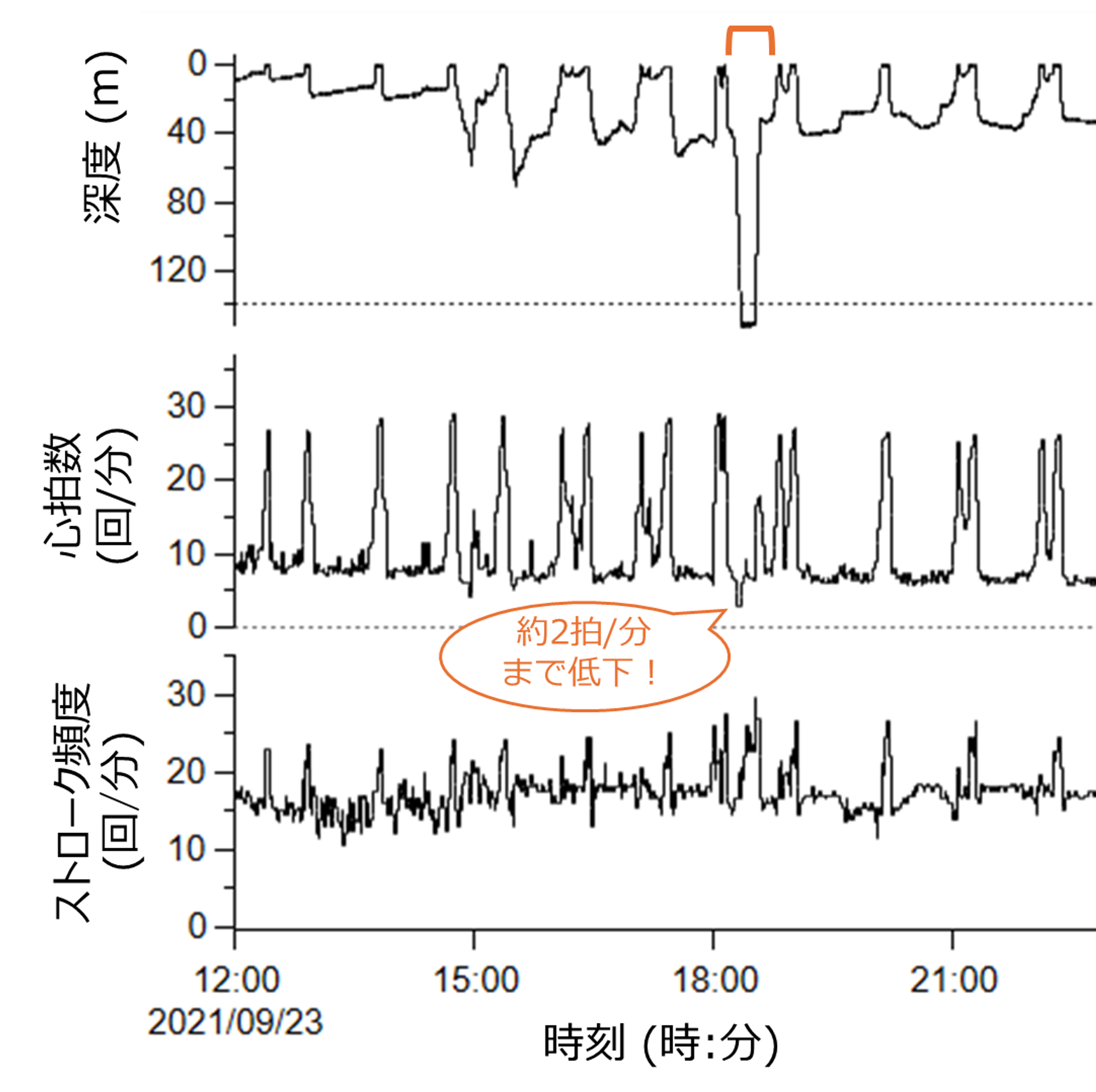

ウミガメの心拍数は潜水中に1分間に2回まで低下!

2024年08月06日(火)

はじめまして。大気海洋研究所 行動生態計測グループの齋藤綾華です。私はバイオロギング手法を利用して、ウミガメの心拍数を測定する研究をしています。今回は、⾃然環境下でアカウミガメの⼼拍数を初めて測定した研究結果をご紹介します。

海洋で生活するクジラやペンギン、ウミガメなどの動物は、人と同じ肺呼吸動物ですが、息を止めた状態で深く長く潜⽔することができます。このような潜水行動を可能にしている⽣理的な仕組みの解明は重要な研究課題です。しかし、爬虫類(ワニ類、ウミヘビ類、ウミガメ類など)の場合は、自然環境下で潜水中の心拍数を測定した研究はこれまでに4例しかありませんでした。特にウミガメ類は海を深く潜る唯一の爬虫類ですが、甲羅があるため心拍数を測定するには体内に電極を埋め込む手術をする必要がありました。その研究の困難さからウミガメ類では、自然環境下で潜水中の心拍数を測定した研究はオサガメの1例しかなく、海生爬虫類が深く潜るときの心拍数はほとんど研究されていませんでした。

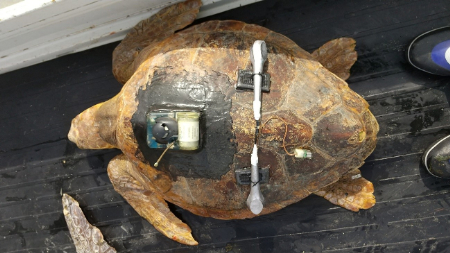

私たちの研究グループでは、ウミガメの甲羅に特殊な電極を貼り付けることで、手術をせずに精密に心拍数を測定する独自のバイオロギング手法の確立に取り組んできました。本研究ではこの⼿法を⽤いて、アカウミガメが⾃然環境下で⾃由に潜⽔するときの⼼拍数と行動を調べました。

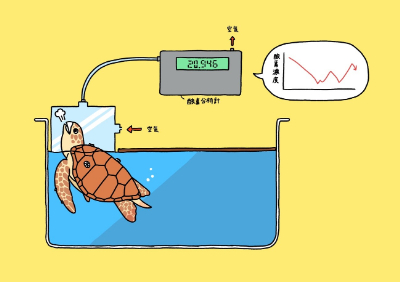

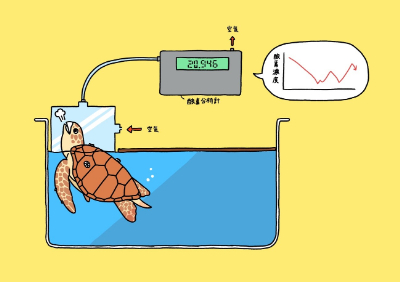

調査は2021~2023年の夏季(7~9⽉)に、岩手県から宮城県にかけての三陸沿岸域で行いました。地元の漁師の方々の協力のもと、実験に使うウミガメを集めました。ウミガメの心電図を測定するには、お腹側に電極を貼り付けます(図1)。

電極から延びているコードは、背中側の記録計に接続されています。

皆さんの中にも、健康診断などでコードがついた吸盤やシールを胸に貼り付けて心電図を測定された経験がある方もいるのではないでしょうか。実はウミガメも、人と同じように心臓をはさむように電極を貼り付けることで心電図を測定できます。ただし、ウミガメは水中で生活するので、電極はしっかり防水する必要があります。そこで、電極の上に人用の防水仕様の絆創膏を貼り付けています。子供の頃、怪我をしたときに使っていた絆創膏を、ウミガメの実験に使うことになるとは思ってもいませんでした…。

電極にはコードがついていて、小型の記録計に接続することで、4日間程度の心電図データを記録できます。心電図記録計と一緒に、行動記録計と発信機を浮きに入れ、ウミガメの背中側に取り付けてから海に放流します。放流するときには、ウミガメが元気に海を泳ぎ、問題なく装置が切り離されデータが回収できるように毎回お祈りしています(図2)。

ウミガメに取り付けた装置は3日後に自動的に切り離され、海面に浮かんでくるので、発信機からの信号を頼りに回収します。何度か失敗もありましたが、無事に5個体のアカウミガメからデータを得ることができました。

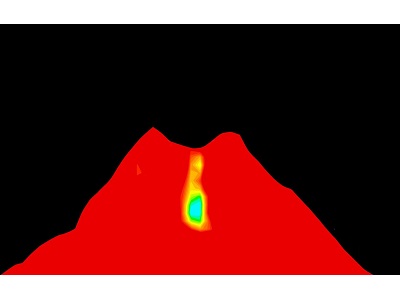

データを解析した結果、アカウミガメは海で数分から最大63分、深度1mから最大153mの範囲で潜水していました。いずれの潜水でも、潜水を開始して数分以内に心拍数は大幅に低下していました(図3)。心拍数の平均値を計算したところ、海面で呼吸するときは1分間に約21回でしたが、潜水するときは1分間に約13回となっていました。特に、アカウミガメが140mより深く潜ったときには、ある程度ストローク(泳ぐときにひれをかく動き)をして泳いでいたにもかかわらず、心拍数が1分間に2回という非常に低い値まで急激に低下していました(図3下段)。初めてデータを見たときには何か間違っているのではないかと思ったほどでしたが、とても興味深く、わくわくしたのを今でも覚えています。

アカウミガメはさまざまな深度に潜水していましたが、いずれの場合も潜水するとすぐに心拍数が低下しました。特に140mより深く潜ったときには、ある程度泳いでいましたが、心拍数はなんと1分間に約2回まで急激に低下していました!

さらに詳しく解析したところ、潜水した最大深度が深いほど最低心拍数はより低くなることがわかりました。それに対し、水温や潜水時間、ストロークの頻度といった他の要素が心拍数に与える影響は、ほとんどないか非常に小さいことがわかりました。これまで海生哺乳類や海鳥では、深く潜るほど心拍数がより低くなることが知られていましたが、ウミガメのような爬虫類でも同じ傾向があることが初めてわかりました。したがって、潜水するときの心拍数の低下は、肺呼吸動物に共通した、深く潜るうえで重要な生理的な仕組みであると考えられました。

この研究成果は今年の3月に論文として公開され、日本語で論文の内容を紹介するプレスリリースも行いました。下記のリンクからどなたでもご覧いただけます。

また、今回の研究は新聞などでも取り上げていただきました。皆様からのご支援のおかげで、このような素晴らしい研究成果を得ることができました。この場をお借りして感謝申し上げます。今回、⾃然環境下でアカウミガメの⼼拍数を初めて測定できたことで、たくさんの新しい事実が明らかになりましたが、研究したいことや気になることもたくさん増えました。引き続きウミガメの生理・生態の解明に向け、調査を続けていきたいと思いますので、今後ともご支援をどうぞよろしくお願いいたします。

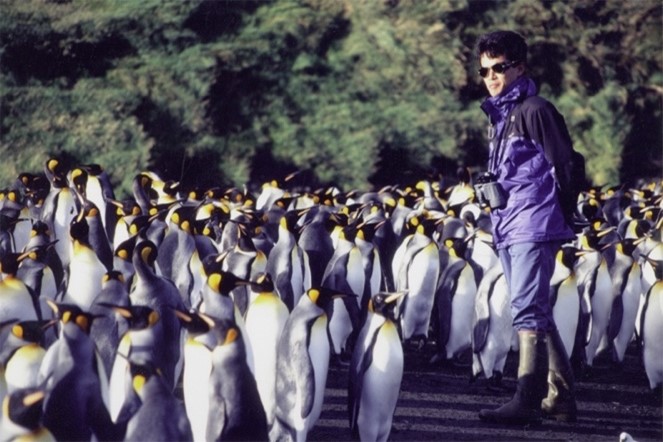

ペンギン目線の映像を求めて亜南極へ

2024年07月03日(水)

初めまして、東京大学 大気海洋研究所 特任研究員の上坂怜生と申します。

私は現在、東大の研究員としてフランス国立科学研究センターに長期滞在し、様々な国籍の研究者と共に研究を行っています。今回は数か月前まで行っていたペンギン調査の様子をご紹介いたします。

今回の調査地はケルゲレン諸島と呼ばれる、インド洋の南極寄りにポツンと存在する島です。「南極」という単語だけを見ると真っ白な氷の世界を想像される方も多いかもしれませんが、夏は意外と草木が生い茂っており雪や氷はほぼ見当たりません。しかし、島のまわりには風を弱める陸地がほとんどないため、年間を通して暴風が吹き荒れており体感温度は非常に寒いです。

そんなケルゲレン諸島には日本どころか世界でもなかなかお目にかかれない様々な生き物たちがいます。島のあちこちにゾウアザラシやオットセイが寝転んでおり、上を見上げれば超大型のアホウドリが飛んでいるなんてこともしばしばあります。今回のターゲットはキングペンギンとマカロニペンギンという2種類のペンギン達です。

ケルゲレン諸島のメインの基地からペンギンがたくさんいるところまでは徒歩で移動するのですが、これがまた大変です。道中には岩がゴロゴロ転がっている場所や沼のようにぬかるんだ場所もあります。また、いくつか河を渡らなくては行けない所もあります。大事な調査道具が入ったリュックを背負い、長靴で約8時間ほど歩き続けると、もう全身くたくたです。それでも調査の終盤にはかなり体力がついており、数時間の移動は全く苦ではなくなるくらいには足腰が丈夫になりました。

ペンギンの調査を行っている間は、ペンギンの繁殖地の近くに立てられた小屋に寝泊りします。ソーラーパネルとガスボンベがあるため、節約しながらであれば電気やコンロを使うことができます。残念ながら水道は無いためシャワーは浴びられませんが、近くに川があるため、飲み水は確保できます。

そんなこんなで過酷な道を経てペンギンの繁殖地にたどり着くと、今後の人生で果たして更新されることがあるのかというくらい1番の絶景を見ることができます。海岸の端から端までびっしりと集まった何十万羽という数のペンギン達です。

水族館での姿を見るとなかなか想像しづらいですが、ペンギンは種類によってはなんと数100mの深さまで潜って餌を採っていることが判明しています。こういった研究はペンギンに深度計や加速度計(体の動き)を装着することで調べられてきました。つまり、どれくらいの深さにいるときに体やくちばしが激しく動いているかを調べることで、餌を採るタイミングや量が明らかになってきたわけです。

では、ペンギンは具体的にどのようにして餌を捕まえているのでしょうか?逃げ回っている魚を追いかけているのでしょうか?これを調べるためにペンギンの背中に小型のカメラを装着するのが今回のメインミッションです。

ただ装着するといっても、ペンギンは思いのほか力が強くて大変です。一人がペンギンを股の間にはさんで抑えて、もう一人が装置を付けるのですが、体重10kgもあるキングペンギンはしばしば大暴れしてスルリと股の間から抜けだしたりもします。また、くちばしでガブガブと噛みついてくるため、生傷も絶えません…。

さらに、装着した記録計を回収するのはもっと大変です。いつ海から帰ってくるか分からないペンギンを、寒い中で凍えながら時には雨雪の降る中でひたすら待ち続けなくてはいけないからです。そのぶん装置を背中に抱えたペンギンが海から帰ってくるところを双眼鏡で見つけられたときは大喜びでした。

そんなこんなで過酷なフィールド調査でしたが、結果は大成功でたくさんのデータを入手することができました。現在はビデオを何度も見返したり体の動きと見比べたりしている真っ最中です。

皆様からのご支援のおかげで、またひとつペンギンの謎が解き明かされようとしています。動物の行動研究や生態系の保全はひとつひとつの発見の積み重ねによって成り立っており、ペンギンの餌採りの秘密もまたその中の1つと言えます。

温かい支援に心から感謝いたします。日々動物のために頭をこねくり回している研究室のメンバーの大きな励みになっておりますので、今後ともご支援をどうぞよろしくお願い致します。

ペンギンと円安と闘う研究者、引き続き精進して参ります。

小さな体でも深く長く潜れるインドネシアの“姫”ウミガメ

2024年06月01日(土)

はじめまして。大気海洋研究所行動生態計測分野・特任研究員の福岡拓也と申します。本研究室で博士号を取得した後、6年ほどの武者修業期間を経て、今年度から舞い戻ってまいりました。今回は武者修行直前に行っていたインドネシアでのウミガメ調査のお話です。

みなさんは“ヒメ”と名前の付く生物にどんな印象を持っていますか?

ヒメボタル(昆虫)にヒメマス(魚)、ヒメハブ(爬虫類)、ヒメアマガエル(両生類)と、様々な分類群にヒメという名の付く生物がいます。彼らに共通するのは、その種類の中で比較的小型な種であるということです。実際、今回の主人公であるヒメウミガメは、世界に8種(意外と少ない!)いるウミガメ類の中で最も小さな種です。どうやら日本人は「ヒメ=姫=小さい」という認識を持っているようです。

そんなヒメウミガメが予想以上に高い潜水能力を持っていることを示した研究成果がこのたび学術論文として出版されましたので、論文の内容とともにインドネシアの西パプア州で行った野外調査の様子をご紹介します。

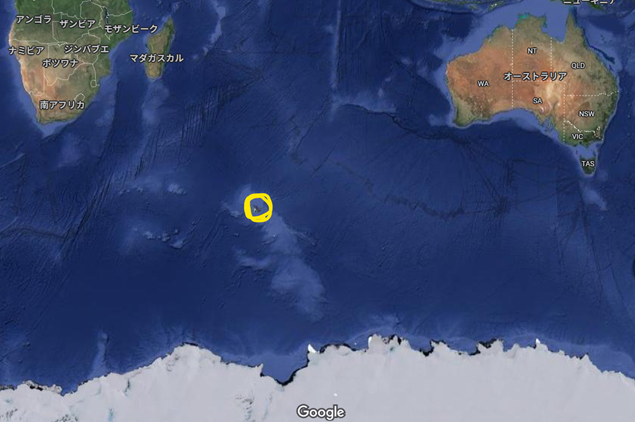

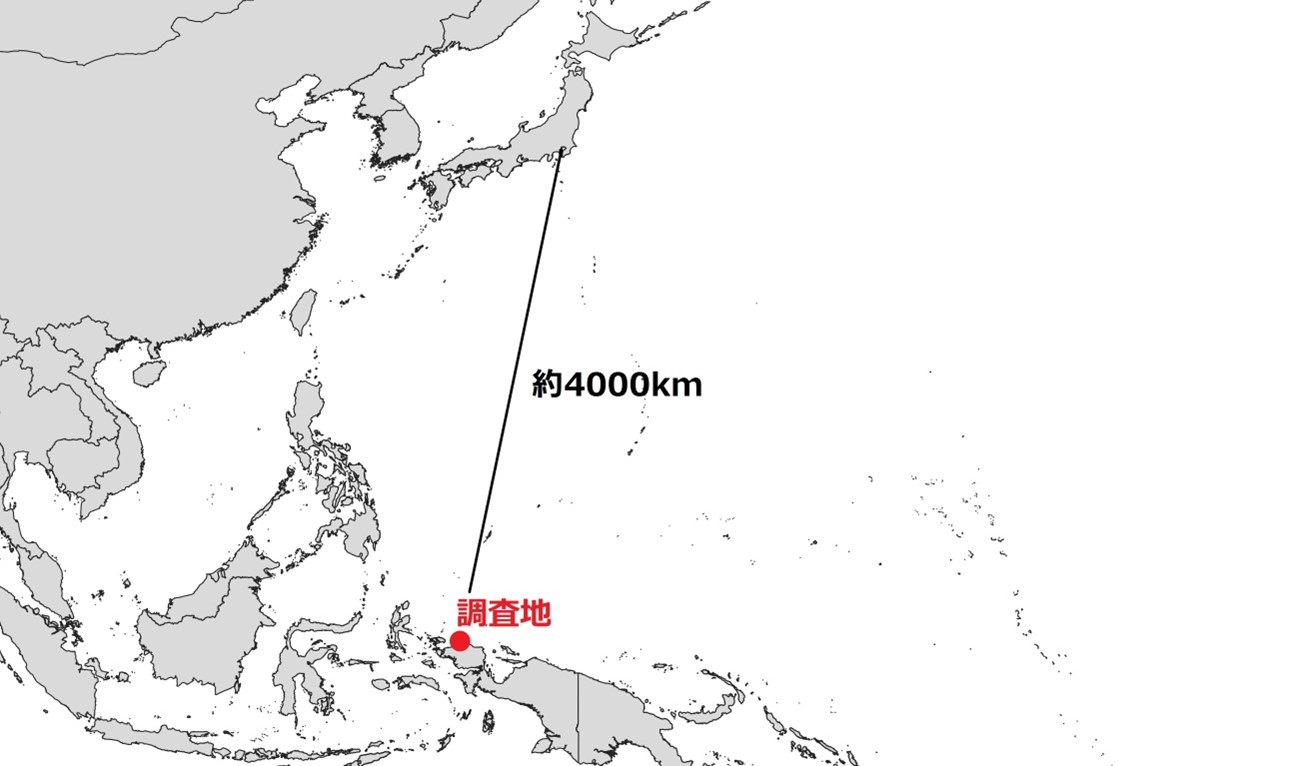

オーストラリアの北にニューギニア島という日本の国土の約2倍もある大きな島があります。その西半分がインドネシア領(反対側はパプアニューギニア領)で、その北西部にある西パプア州・バードヘッド半島の最北端にウミガメの産卵地があります(下図1)。

と、二文で簡単に書きましたが、実際に調査地へ行くのは簡単ではありません。調査地は西パプア州という地域に属しており、そこの州都であるソロンという都市までは羽田からジャカルタを経由して飛行機が就航しています。

しかし、そこから150km以上離れた調査地まで飛行機はもちろん公共交通機関もありませんし、調査地周辺は熱帯雨林で道路すらありません。そこで、小型の漁船(図2)で半日以上かけて向かい、波が穏やかであればようやく調査地に入れます。ちなみに、波が高い場合には10km以上離れた最寄りの村から重い荷物を背負って歩くことになります。そうならなくて本当によかった・・

調査地では熱帯の日差し、なんだか赤茶色っぽい色のついた飲み水、マラリア(蚊)、狂犬病(野犬)、日本脳炎(野ブタ)、捕食(イリエワニ)といった様々な脅威に(私だけ)怯えながらウミガメのモニタリング調査を行います。

日中は砂浜を何kmも歩いてウミガメの産卵巣の位置や巣穴を掘って卵の発生状態を確認し、夜は産卵のために上陸した世界最大のカメであるオサガメの計測を行いつつ、目的のヒメウミガメがやって来るのを待ちます。もちろん電気水道ガスはないので砂浜でのキャンプ生活です。こう書くととても大変な調査に思えるかもしれません。そうなんです!大変なんです。自分以外の人達は皆楽しそうでしたが・・・。しかし、後で思い出すと、調査だけでなく熱帯の大自然やそこで生活する人々の暮らしを垣間見れる貴重な体験でした(図3、4、5)。

閑話休題。

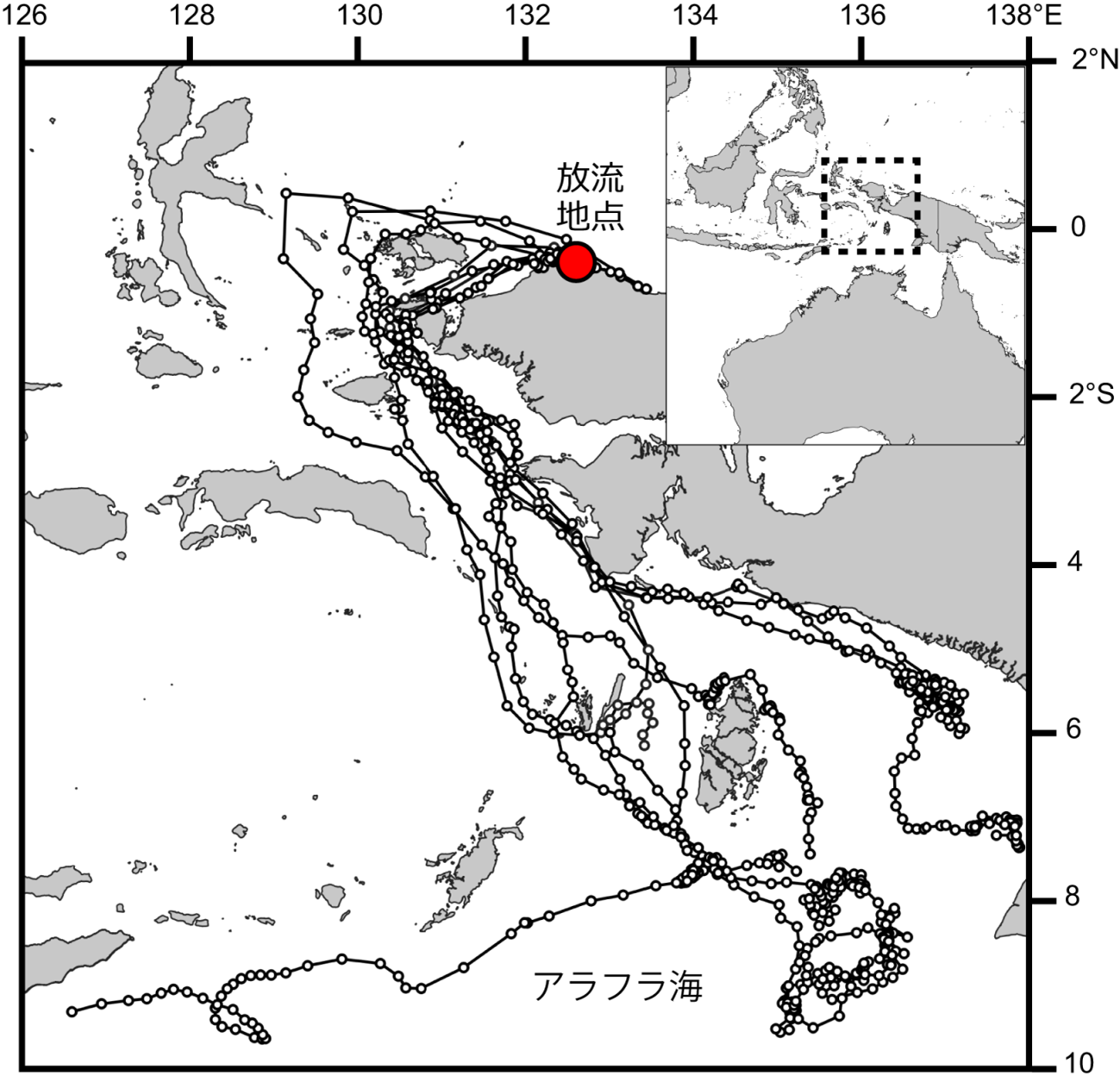

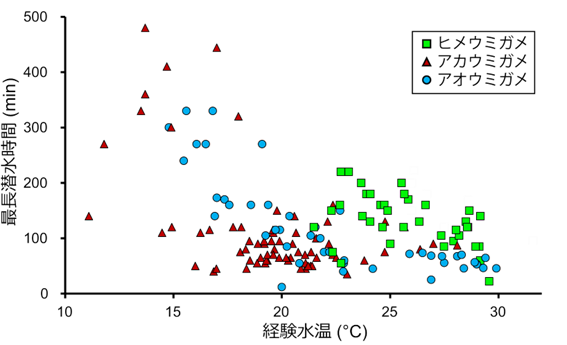

西パプアで産卵するヒメウミガメの回遊ルートや潜水行動を調べるために、2017年から2019年に合わせて10個体のヒメウミガメに人工衛星対応型の電波発信機を取り付けて放流しました。放流後、ウミガメ達はどの個体もニューギニア島をぐるりと半周し、オーストラリアとの間にあるアラフラ海という浅い海へ移動していました(図6)。さらに、潜水行動のデータを見ると、移動中には最大340mまで潜り、アラフラ海の滞在中には最長3時間40分間息をこらえて潜水していることがわかりました。

これは中々に驚きの結果でした。人間や哺乳類からすれば3時間以上息を止めていられるというのも十分驚きですが、ウミガメ類ではもっと長い時間潜っていた記録もあるので、潜水時間だけならそこまで珍しいことではありません。

今回驚いたのは“小さな”ヒメウミガメが“熱帯の海”で長く潜っていることです。過去の研究によって、潜る深さや時間は大型の種類ほど深く長くなることが知られています。また、ヒメウミガメが属するウミガメ類では水温が高くなるほど潜水時間が短くなるという傾向も知られていました。

つまり、インドネシアという熱帯域に生息する小型のヒメウミガメは他のウミガメ類に比べて浅く短い潜水を行うと予想されます。しかし、実際には25℃以上という高水温帯でも長い潜水を繰り返すという予想外の結果が得られました(図7)。

その後、詳細は省きますが、ヒメウミガメの潜水能力を系統的に近いアカウミガメの形態学的・生理学的情報を使って予測したところ、実際の潜水行動を十分に説明できず、やはりヒメウミガメの方が高い潜水能力を持っていることを示していました。今後、どういったメカニズムでヒメウミガメが高水温下で長時間潜っていられるのかを明らかにしていく予定です。

絶滅が危惧されるウミガメ類において個体数変動の重要な鍵となるのは産卵場で、その多くが熱帯や亜熱帯地域に分布しています。私達の主な興味はバイオロギング手法を用いた動物の行動生態にありますが、同時にウミガメの保全団体や現地の人々と一緒になっての産卵モニタリング調査も進めています。

皆様のご支援は、野生動物の生態解明だけでなく、ウミガメの保全や異文化を知ることにもつながっていきます。若い学生が一度行っただけでこうした経験の重要性を感じ、将来に活かしてくれるかどうかはわかりませんが、その機会だけでも与えられたらと思っていますので、今後ともご支援をどうぞよろしくお願い致します。

人生ちょっと変わります、西パプア。

ザトウクジラが拾い食い!?

2024年04月03日(水)

サムネイルイラスト:木下千尋

文章:岩田高志(現 神戸大学 海洋政策科学部・大学院海事科学研究科)

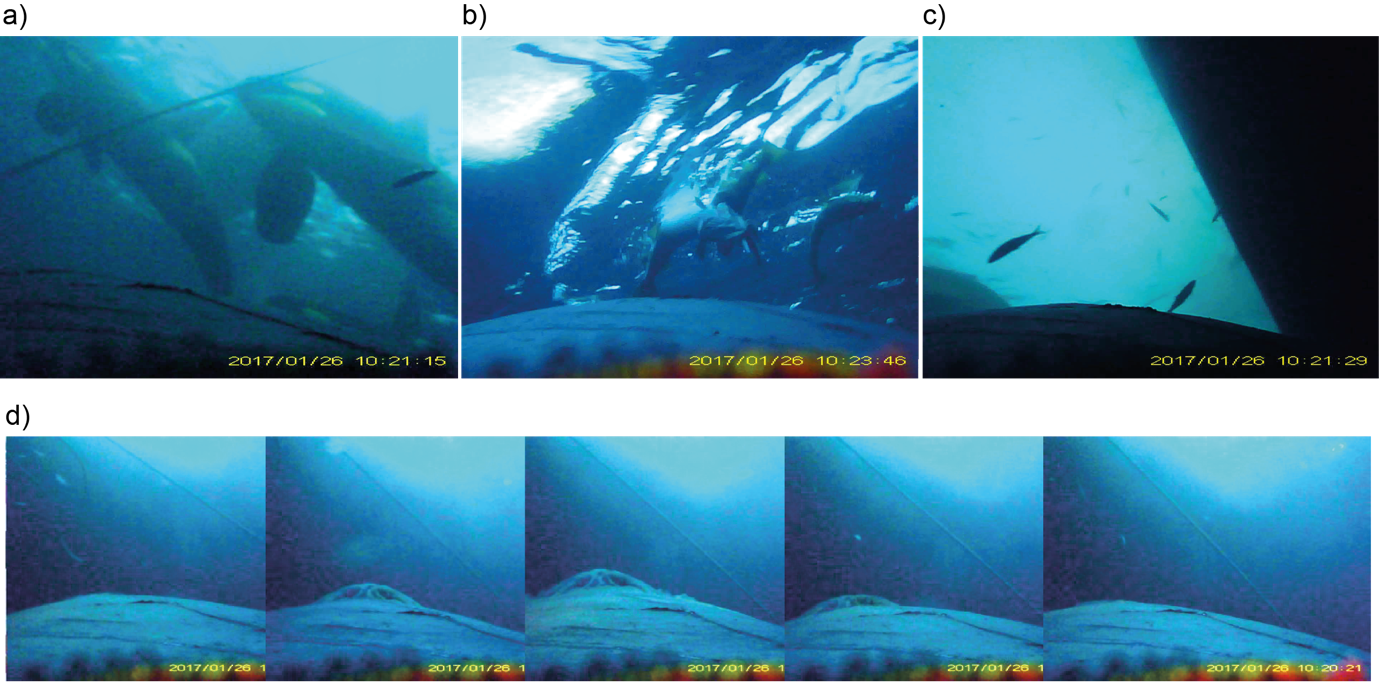

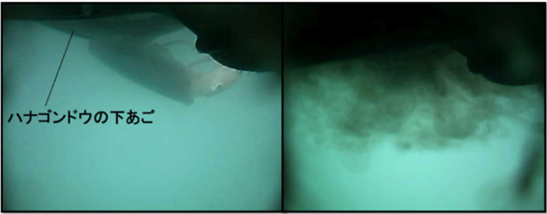

イルカ、アザラシ、オットセイなどの海生哺乳類や、カモメやアホウドリなどの海鳥類は、餌獲りのために漁船周りに集まることが知られています。最近では、ヒゲクジラ類も漁船周りに集まって餌獲りをしていることが報告されています。ヒゲクジラ類(正確にはナガスクジラ科の動物)は、餌の群れに突進をして餌を取るのですが、漁船周りでは餌がまばらに散らばっていることや、突進による漁船への衝突リスクがあるため、突進型の餌獲りをしないことが考えられます。そこで本研究では、ヒゲクジラ類の一種であるザトウクジラが漁船周りでどのように餌獲りをしているのかを調査しました。

調査は、2017年1月にノルウェー・トロムソ沿岸域のフィヨルドで実施しました。クジラに装置を取り付けるときは、小型のボート(約5メートル)でクジラに接近し、約6メートルのポールを使って吸盤で取り付けます。吸盤で取り付けられた装置一式は、数時間後に自然脱落し、海面に浮かんでくるので、装置一式に組み込まれた発信機の電波を頼りに回収します。

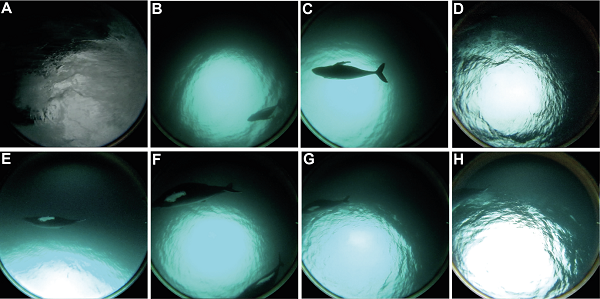

野外調査の結果、ザトウクジラ3個体から、合計32時間の行動データと17時間のビデオデータを得ることができました。ビデオデータから、餌獲りの有無を判定しました。得られたデータのうちの1つは、漁船周りを泳いでいたクジラに取り付けたもので、装置を取り付けた後、クジラが漁船周りに43分間留まる様子が記録されていました(図1)。そのビデオ映像には、漁船から落ちた大量の死んだ魚、それを狙うシャチ、漁船、ロープなどの漁具が映っていました(図2)。さらにそこには、装置を取り付けたクジラが、上顎を挙げて、漁船から落ちた魚をついばんでいる様子が記録されていた(図2)ことから、この行動を「拾い食い」と名づけました。一緒に取り付けた行動記録計には、拾い食いをしている間のクジラは、速く泳ぐこともなく、尾びれもあまり動かしていませんでした。このことは、拾い食いに必要なエネルギーが小さいことを意味します。一方で、拾い食いでは散らばった餌を狙うため、一度に得られる餌量は多くありません。以上のことから、拾い食いは、少ないエネルギーで、少ない餌を食べる、エネルギー節約型の餌獲り様式であることが分かりました。

本研究では、ザトウクジラが、状況に応じて柔軟に餌獲り様式を変えていることを示しました。しかし、拾い食いには、ロープや網などの漁具にクジラが絡まる可能性を含んでいます。漁具への絡まりは、クジラにとって死のリスクがあり、漁業者にとっても、漁具の破損やクジラを救助する際に生じる接触(人とクジラ、船とクジラ)事故のリスクがあります。そのため、クジラの保護・管理の観点、また安全面において、拾い食いは避けるべき事象であることが分かります。クジラが漁船周りに集まってくる環境においては、嫌がる音を出すなど、クジラを漁船や漁具に近づけさせない取り組みが推奨されます。

(a)シャチとロープ、(b)死んだ魚(タラ)、(c)死んだ魚(ニシン)、(d)死んだ魚を食べるために装置を取り付けた個体が上顎をあげている様子。

大きくなって柏に戻れ

2024年03月12日(火)

長谷川隼也(東京大学大学院農学生命科学研究科水圏生物科学専攻 修士課程1年)

皆様はじめまして。大気海洋研究所行動生態計測グループの長谷川です。

私はR5年度から本研究室に所属しており、バイオロギング研究を開始しました。研究対象としているのはオオミズナギドリというミズナギドリ目ミズナギドリ科の海鳥です。オオミズナギドリは毎年春頃に繁殖のため日本近海の島嶼へやってくる渡り鳥で、秋になると南半球のパプアニューギニア周辺まで越冬しに行きます。オオミズナギドリの繁殖期にあたる2023年の夏に、私にとって初めてのオオミズナギドリ調査に参加しました。

オオミズナギドリ調査の舞台となるのは、岩手県大槌町に位置する船越大島という無人島です。とても面白い調査なのですが、バイオロギング支援基金の活動報告には無人島調査の話がありません。そこで今回は、多くの写真を用いながら、無人島でのオオミズナギドリ調査がどのように行われているのかをお伝えしようと思います。

少々長いですが、是非とも最後までお付き合いいただき、少しでも雰囲気を感じ取っていただけたら嬉しい限りです。

調査を行うのは8月から9月なのですが、そのための準備は春から開始しました。

準備したのは主に機器類や書類で、中でも機器類の使い方を習得するのに多くの時間を費やしました。バイオロギングは未だ発展途上な研究手法で、その装置は私たちが持つスマートフォンやパソコンのように完全なものではありません。そのため同じ製品でも個体差があったり、同じような装置でも使い方が全然違ったりします。したがって通常の使い方に加え、何番の装置はこういうクセがある、というようなこともメモしながら少しずつ扱えるようにしました。書類に関しては、船越大島はタブの木の北限であるため天然記念物に指定されており、関係省庁から許可を得るための「現状変更届」などといった公的書類が必要になります。他にも、動物を使った実験を行うための「鳥獣捕獲許可申請書」や「動物実験計画書」などたくさんの書類を用意しました。研究室に入室したてで右も左も分からない私も、先輩方に尋ねながらなんとか準備することができました。

準備などでそれなりに忙しくしていましたが、初めての調査が楽しみで落ち着かない私を嘲るように、準備期間はひどく長く感じました。

ようやく8月になると、いよいよ調査が始まります。今年の調査は22日からを予定していましたが、初心者に対する洗礼として最初の試練が降りかかってきました。船が出ないのです。

私たちの調査地は無人島にあるので、本土から船で渡る必要があります。そのため地元漁師さんに船を出していただくのですが、無人島の船着場となる岩の足場が悪く、風の影響で波が高いと船を出してもらえません。一方、雨が降っていても風がなければ船が出ることはあります。今回も台風の影響があり、調査の開始を3日間ほど延期することにしました。研究室がある千葉県柏市で待ちぼうけを食らうことになった訳ですが、その分準備期間が増えたと捉えて、岩手に移動してからやろうと思っていた細々した準備をするなどして調査に備えました。フィールド調査は自然相手だから予定通りにいかないということを調査前に学ぶことになりました。

25日に岩手に移動しましたが、波が高い状態が続き、結局島に入ることができたのは31日のことでした。

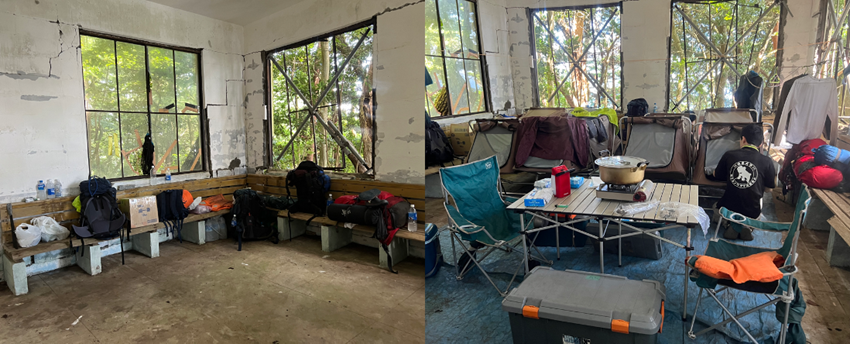

朝8時に港を出発し、島で1週間生活できる分の食料やテントなどを島に運びました(調査が第一の目的なので、某有名テレビ番組のようにサバイバル生活はしません。とったどぉーなんてもっての外です)。無人島に初上陸し、ここが無人島かぁとあまり無人島感がない岩場で救命胴衣を脱ぐと、すぐに拠点へ荷物を運び始めます。学生や教員など10人ほどで、ひとり2〜3往復します。船越大島は海抜60mほどの島で、拠点もだいぶ高い位置にあり、もちろん道の整備もしっかりとされていないのでもはや山登りです。汗だくになって荷物運びをしました。

拠点となるのは、何十年か前に船越大島を観光地化するために作られた売店の廃墟です。今では観光客が訪れることはなく、建物だけが残っています(無人島なのに建物があることにがっかりした学生は私が初めてではないはずです)。拠点を設営して一息つくと、私を含む学生3人と指導教員の合計4人以外の日帰りのメンバーは昼頃に本土へと帰っていきました。沖合800mとはいえ、通信環境もまともにない無人島に取り残されるのはどこか不安になりました。

夕方までは巣で親鳥の帰りを待っている雛鳥の体長計測を行いました。地面に這いつくばり、穴を掘って巣を構えるオオミズナギドリの巣に手を入れて雛鳥を捕まえます。調査期間中に徐々に大きくなっていく雛鳥の成長を追えるのはとても新鮮味がありました。

18時半頃、食料として持参した缶詰やレトルト食品を食べていると、拠点周りの薄暗い森林から「ピーー!」や「グーー」といったオオミズナギドリの鳴き声が聞こえ始めました。私たちヒトとは異なり、「ピーー!」という高い声はオスが、「グーー」という低い声はメスが出します。いよいよオオミズナギドリ調査が始まる!と覚悟を決めると同時にそのことを忘れるくらいワクワクしてじっとしていられませんでした。先生からは「調査は持続可能な6割程度の力で取り組もう」と言われていましたが、フルスロットルで調査に立ち向かうつもりで張り切っていました。

1時間もしないうちにそこかしこにオオミズナギドリ(とカマドウマ)がいる状況になり、鳴き声がうるさい(地面でピョンピョン跳ねるカマドウマが煩わしい)と感じるくらいになりました。この時に感じたのは、鳥の世界にお邪魔している、という感覚でした。正直居心地が悪くなるくらい肩身が狭い思いでした。今までダーウィンが来た!などの番組で繁殖地に集まる鳥の映像は見たことがありましたが、圧巻でした。やっと研究者のフィールド調査感が出てきて、嬉しくて心だけでなく私自身も踊りました。

18時半頃に島に帰ってきて、明け方5時前にはまた採餌のために飛び立つというオオミズナギドリの生態に合わせるため、島では夜型の生活をしながら調査をします。21時からオオミズナギドリにデータロガーを装着する作業に取り掛かり、私もデータ取得のため必死に見様見真似で作業しました(教員から「案外器用だな」とお褒め?の言葉をいただきました。嬉しい)。オオミズナギドリに触れることや自身のバイオロギング研究デビューに感動する暇もなく、タスクをこなすので精一杯でした。それでもデータロガー装着中、空からオオミズナギドリが降ってきて体当たりされたり、抵抗するオオミズナギドリに噛まれたり、目の前で羽ばたかれて翼で顔面を叩かれたりとすこぶる楽しいことばかりでした。

21時から休みを入れて3回に分けて作業をし、あっという間に初日の調査が終わりました(この時すでに午前3時)。小腹を満たしてからボディーシートでこれでもかと体を拭いた後(水道はなく、ましてやシャワーなんてもちろんありません)、痛いくらいスースーする状態で一人用テントに入りました。さぁ寝ようと思ったはいいものの……「ピーーー!」「グーーーーー」オオミズナギドリの声がうるさくて寝付けません。その場凌ぎのノイズキャンセリングイヤホンをして寝ました(オオミズナギドリの騒々しさは、疲れには流石に敵いませんでした)。

オオミズナギドリは繁殖期間中、日帰りまたは数日の短い採餌トリップと、長いと12日ほどにもなる5日以上の長い採餌トリップを繰り返します。何日か経てば巣に戻ってくるので、装着したロガーを回収できます。私が装着したデータロガーも、無事に戻ってきました。何事もなかったように、記録を取って戻ってきてくれたオオミズナギドリがなんだか頼もしく、また妙に愛おしく感じられました(協力してくれてありがとう)。 こうした調査を、メンバーを入れ替えて長くても4、5日の周期で交代しながら調査を進めました。

本土に戻り、たっぷりとシャワーを浴びて炊き立てのホカホカご飯を食べた後、回収したデータロガーの記録確認を行いました。データロガーをパソコンに接続すると、一部を除きしっかりとデータが取れていました。この時の高揚感は今でもはっきりと覚えています。夜眠るときに枕元に置いておきたいくらい、とても嬉しかったです(あの感情は何なのでしょう)。

私は本土でも、オオミズナギドリの心電図を取得する実験がありました。島にいても本土に戻ってもオオミズナギドリに触れることができて毎日幸せで充実した調査期間でした。

恥ずかしい話ですが、調査期間が終了し、柏市へ帰ろうと準備していた最終日に私は体調を崩してしまいました。搬送先の病院では、皮肉にも私自身の心電図がとられ、先生の診断材料となりました(全く問題はありませんでした)。最近食べたもの、生活リズム、体調などについて根掘り葉掘り聞かれ、出された診断は「特に問題なさそうだね。慣れないことが続いて気疲れしたんだろう」でした。病院に行くなど思いの外大ごとになってしまい、予定通りにひと足先に柏に戻った先生や先輩方に大きな心配をかけた割にはあっさりとした診断に、なんだか申し訳ないような気持ちになりました。と同時に、自分が医者から質問されたことは自分がオオミズナギドリで調べたいことだと思いつき、バイオロギングの行動研究ではなく鳥語を研究する道に行けばよかったか?と、ぼーっとした頭によからぬ考えが浮かんだりしました。ともあれ、自分の体力を過信したことを反省し、やはり調査は6割の力で臨むべきだと実感しました。

オオミズナギドリの親鳥は10月から11月にかけて越冬のため南へ向かい、これを追うようにして十分大きくなった巣立ち雛が後から南へ向かいます。半日の入院中に点滴を受けながら「私も初めての調査を経てひと回りもふた回りも成長することができた。自信を持って柏市に帰ろう」と自分を鼓舞しました。その甲斐あってか、病院から帰った翌日には元気を取り戻し、胸を張って帰ることができました。心配や迷惑をかけた方々に特に問題はなかったと報告に行くと、「まぁ、M1(修士課程1年の意味)で初めての調査だったからね」と優しい言葉をかけてもらいました。この言葉の裏側に「来年からはしっかりしろよ」というメッセージがあると考えるのは深読みのしすぎでしょうか。

少し話が逸れましたが、柏に戻ってからは調査中に得られたデータを着々と解析しています。やはり、初めて自分で取ったデータには愛着のようなものがあります。特に成果として目に見えてわかりやすいビデオデータには文字通りの鳥瞰図が映し出され、何度観てもニヤつきは止みません。同時に、たくさんのデータが手元にあるということは、それに相当する数のオオミズナギドリたちに協力してもらったということを意味しています。実験協力者である彼らにも恩返しができるように、責任を持って一生懸命解析していきたいと思います。

ここまで述べてきたようなとても充実した無人島での調査は皆さまからのご支援で成り立っているものです。安全に調査を遂行し、研究活動に没頭できるのは皆様のおかげです。 私の楽しい調査のため、というと独りよがりが過ぎるように聞こえますが、得られた結果は今後しっかりと解析して成果を世に発表していきます(面白いことがわかったらこの「活動報告」でも報告いたします)。

こうした一連の活動にぜひお力添えをお願いします。

長々と読んでいただきありがとうございました。

『第8回バイオロギング国際シンポジウム』が開催されます!

2024年01月24日(水)

2003年に第1回国際シンポジウムを東京で開催する際に「バイオロギング」という言葉が生まれました。その後、2〜3年間隔で世界各地でバイオロギングシンポジウムが開催されています。この度21年ぶりに再び東京で第 8 回バイオロギング国際シンポジウムが開催されます。それに合わせて、高校生と大学生向け講演会を、対面とオンラインを融合したハイブリッド形式で開催します。大学に所属する研究者と NASAの宇宙飛行士が、野外生物学に関する魅力的で親しみやすい話をします。英語による講演では、適宜日本語による解説も行います。講演後には質疑応答の時間も設けます。会場への参加者は400人で締切りますので、お早めの応募をお願いします。まずは高校生・大学生で募集しますが、人数に余裕があればそれ以外の方々にも対面で参加していただけます。

第8回バイオロギング国際シンポジウム講演会

“バイオロギングで自然の秘密を解き明かす: 海中から陸上、そして宇宙への旅”

“Unlocking Nature’s Secrets: A Journey from Underwater Realms to Outer Space”

日時: 2024年3月9日 10:00~12:30

会場: 東京大学 伊藤国際学術研究センター地下2階 伊藤謝恩ホール

参加費: 無料(対面参加者には特製クリアフォルダとエコバッグをプレゼント)

申込み:フォームもしくは上記QRコードからオンラインでお申し込み下さい。

お問合せ: bls8tokyo@gmail.com

<プログラム>

10:00〜 イントロダクション(楢崎友子)

10:10〜 講演1 東京大学大気海洋研究所教授 佐藤克文

10:45〜 講演2 ロクサーヌ・ベルトラン博士(カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校)

11:20〜 講演3 クリスチャン・ルッツ博士(セントアンドリュース大学)

11:55〜 講演4 ジェシカ・ミアー博士(NASA) オンライン講演

<講演者>

1. 東京大学大気海洋研究所 教授 佐藤克文

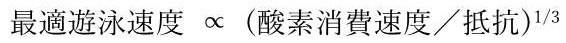

“高校までに学ぶ物理や化学で解き明かす水生動物の行動 Why should you study physics and chemistry?: Swimming behavior of aquatic animals governed by the laws of physics”

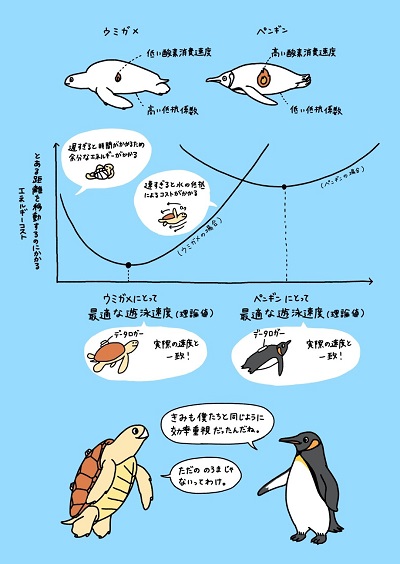

右の表紙に見覚えはありませんか?中学校2年の国語教科書に、「生物が記録する科学:バイオロギングの可能性」という文章が掲載されています。それを読んでいる皆さんは既にバイオロギングという言葉を知っているかもしれません。教科書に書ききれなかったバイオロギングの話、動物搭載型の加速度記録計を使ってこれまで明らかにしてきたペンギンやアザラシの浮力に対応した遊泳行動について紹介します。

2. ロクサーヌ・ベルトラン博士(カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校)

Dr. Roxanne Beltran (University of California Santa Cruz)

“ゾウアザラシを通じて明らかになった広い外洋の世界 Open Ocean Discoveries Through Partnerships with Elephant Seals”

米国カリフォルニアで繁殖するキタゾウアザラシや南極のウェッデルアザラシの研究をしています。人による観測が遅れている海の外洋域について、様々なデータロガーを取り付けたアザラシがどんな発見をもたらしたのかについて紹介します。「A Seal Named Patches」という児童書も出版しています。

3. クリスチャン・ルッツ博士(セントアンドリュース大学)

Dr. Christian Rutz (University of St Andrews)

“私の旅:道具を使う熱帯のカラスの研究から地球規模の協力ネットワークの構築までMy journey from studying tropical, tool-using crows to building global-scale collaborative networks”

道具を使うニューカレドニアのカラス(写真で手にしているのがその道具です)を観察するという課題をきっかけに、野鳥に搭載するビデオロガーを使った研究を進めてきました。国際バイオロギング協会の会長であり、パンデミックによるロックダウン中の動物の移動パターンの変化を研究する新型コロナウイルス感染症バイオロギング・イニシアチブの研究代表者も務めています。

4. ジェシカ・ミアー博士(オンライン講演)

Dr. Jessica Meir (NASA)

バイオロギング手法を用いたエンペラーペンギンの潜水生理学研究でスクリップス海洋研究所から博士号を取得した後、2013年にNASAの宇宙飛行士に選ばれました。最近第61次と62次の長期滞在で国際宇宙ステーションの航空技術者を務めました。宇宙でも使われているバイオロギングの技術について、オンラインで講演します。その後、質疑応答にも参加します。

モデレーター:楢崎友子博士(名城大学)

日本の高校を卒業後、動物学と英語を一緒に学びたくてオーストラリアの大学へ進学。卒業後は、東京大学大気海洋研究所の大学院に入り、ウミガメを対象としたバイオロギング研究で博士号を取得しました。その後、博士研究員としてセントアンドリュース大学に留学し、クジラを対象としたバイオロギング研究を進めました。現在は名城大学の教員として、日本国内のフィールドや水族館で研究を行っています。

2023年活動報告

-バイオロギング支援基金活動報告-

2024年01月17日(水)

今年度、41件で総額1,359万5000円を寄付していただきました(2024年1月10日現在)。コロナ禍による活動制限がほぼ無くなり、コロナ前の野外活動状況に近づいた嬉しい年となりました。

活動報告として既にHP上にてお伝えしているとおり、岩手県・山口県・和歌山県といった国内各所、さらにカナダにおける野外調査を遂行することができました。皆様のサポートを受けて実施した野外調査の結果は、現在博士研究員や大学院生達がとりまとめ中です。

今年度は計2名の修士課程修了者がいるため、2月上旬の発表会に向けて毎日夜遅くまで研究室は賑わっています。2023年は計10本の原著論文を公表する事ができました。その中でも2022年3月に博士号を取得し、現在当研究室で博士研究員として活躍中の上坂怜生さんの研究成果が10月にeLifeに公表されました。論文タイトルは“Wandering albatrosses exert high take-off effort only when both wind and waves are gentle(風と波の両方が穏やかな時、離陸に苦労するワタリアホウドリ)”というもので、大気海洋研究所のWebsiteを通してプレスリリースされ、国内外のマスメディアで大きな反響がありました。現在上坂さんはインド洋亜南極圏でペンギンを対象とした野外調査中です。3月に帰国したら、楽しい野外調査報告を行ってもらいます。

例年通りバイオロギングカレンダーを作成し、継続支援をして下さった方と3万円以上のご寄付をいただいた方へ年末にお送りしたところです。3月上旬には第8回国際バイオロギングシンポジウムが東京大学で開催されます。それに合わせて3月9日に、高校生と大学学部生向け講演会を実施予定です。その他、例年通り来シーズンの各種野外調査を着実に遂行できるよう、今から準備を着々と進めています。

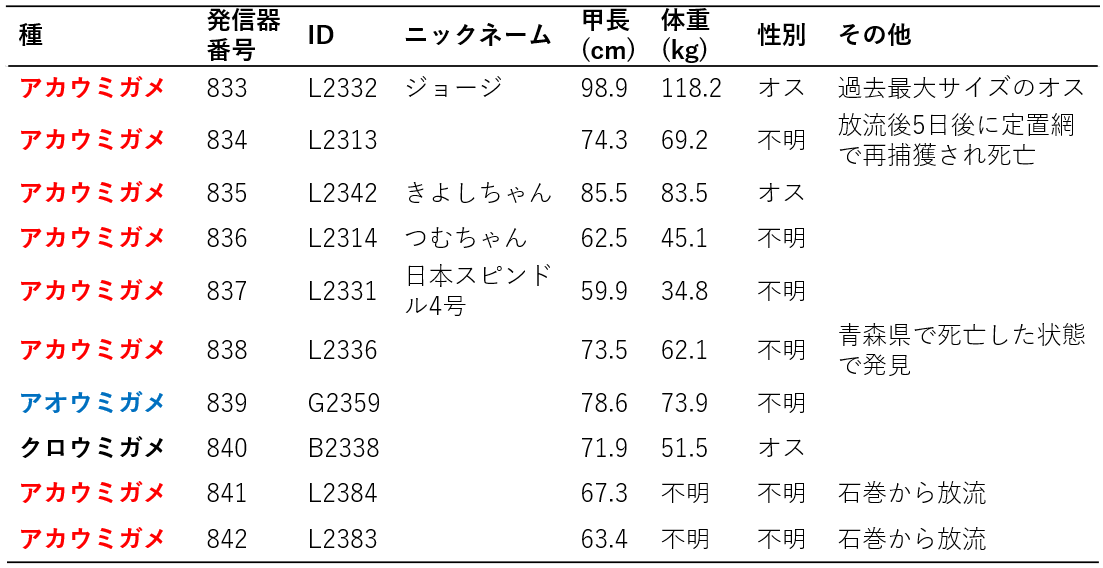

2023年の夏に、アカウミガメ8頭、アオウミガメ1頭、クロウミガメ1頭の計10頭に人工衛星発信器をつけて、岩手県釜石市から8頭、宮城県石巻市から2頭を放流しました。さらに11月にはアオウミガメ1頭に人工衛星発信器をつけて千葉県の館山市から放流しました。ジョージと名付けられたオスのアカウミガメ(L2332)は、残念ながら2023年10月26日を最後に通信が途絶えています。きよしちゃんと名付けられたアカウミガメ(L2342)とつむちゃんと名付けられたアカウミガメ(L2314)もまた、残念ながら2023年8月8日および8月3日を最後に通信が途絶えています。 これまで、数ヶ月毎に基金のHPの「活動報告」ページにおいてウミガメ達の経路を報告してきましたが、この度、皆様がいつでも好きなタイミングでウミガメの経路を確認できるシステムを作成したのでご紹介いたします。

◆Biologging intelligent Platform (BiP)のサイトに行く

LIVEMAPボタンを押す ページの上には一覧表があり、個体データが並んでいます。自分が見たい個体を左端のカラムでマークを付けます(複数個体選択可能)。 その後右上にstartとendの日付を入力する箇所があるので、ここに例えば2023/7/19と今の日付を入力し「GET DATA」ボタンを押すと個体の経路が地図上に現れます。

現在、日本スピンドル4号と名付けられたアカウミガメ(L2331)ともう一頭のアカウミガメ(L2387)、そして館山から放流したアオウミガメ1頭(TG23117)からの通信は続いています。是非とも今後も行方を見守ってください。

■ご寄付の使途

いただいたご寄付は以下の目的のために、活用いたしました。

温かいご支援を賜り、ありがとうございました。

・バイオロギング装置回収用のVHF発信器

・魚類装着用人工衛星電波発信器

・大槌町ウミガメ調査旅費

・博士研究員雇用費

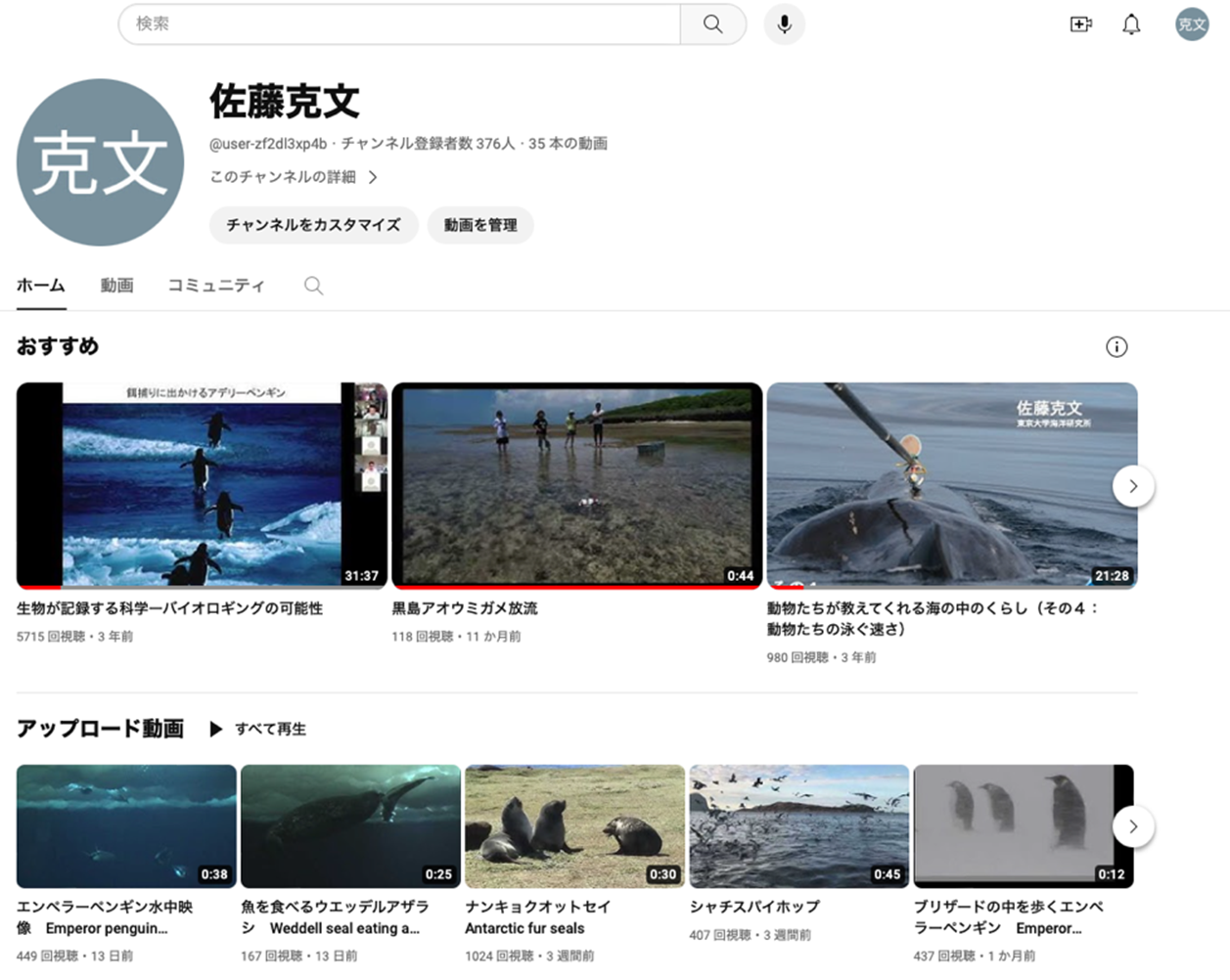

佐藤克文YouTubeチャンネル紹介

2023年12月05日(火)

コロナ禍をきっかけにYouTubeチャンネルを始めました。

私が書いたバイオロギングを紹介する文章が2016年より光村図書の中学2年生国語教科書に使用されています。中学校の先生が、外出自粛中の遠隔授業で補助資料として使える様に、私自身の講演を動画で配信したのです。その後、東京書籍の小学5年生国語教科書にも私の文章が掲載されるようになったので、小学生向けの講演もアップロードしました。

その他、私が講演会でしばしば使用する動物たちの動画が大量に私のPCに眠っています。これらも公開するべく、YouTubeチャンネル上で次々と公開するようになりました。中には1ヶ月間で7万回の視聴者を得たヒット動画もあります。是非皆さん、私のチャンネルを訪れて、動画を見てやって下さい。

「イエーイ、エイ!」今年の秋のホシエイ調査

2023年12月01日(金)

Yay, Rays! This Year’s Autumn Pitted Stingray Field Research

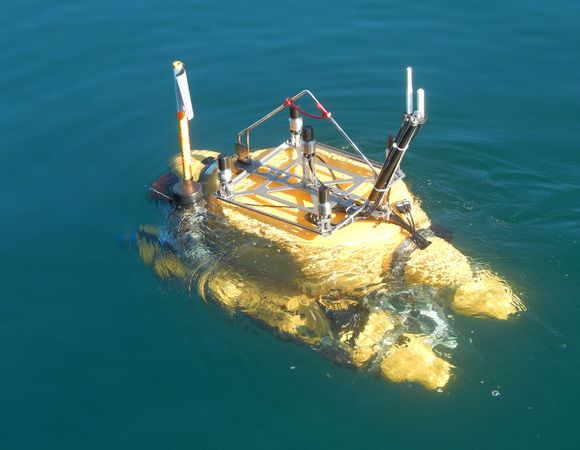

Starting last autumn, I began participating in the research of pitted stingrays (Bathytoshia brevicaudata) in the Seto Inland Sea. Specifically, we are using biologging to study the swimming and migratory behavior of the species. In September 2023, we returned to Kaminoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. There was a feeling of uncertainty as we approached the field site, as we had heard that apparent damages from rays had decreased recently. The observation of what appeared to be decreased damages was positive news; we also hoped to deploy a sufficient number of miniPAT tags (which record depth, water temperature, 3-axis acceleration, and light level for geolocation) in order to further address the challenges encountered with sharing the Seto Inland Sea with this species.

私は昨秋から瀬戸内海のアカエイ(Bathytosia brevicaudata)の調査を始めました。 具体的には、バイオロギングを駆使して、遊泳と移動を研究しています。 2023年9月、私たちは山口県上関市に再びやって来ました。 最近はエイによる明らかな漁業被害が減少していると聞いていたため、調査のためのエイを捕獲できるだろうかと不安を感じながら現地に向かいました。しかし、 被害が減少したこと自体は明るいニュースでした。 私たちは、瀬戸内海でこの種と共有する際に直面する課題に対応するために、十分な数の miniPAT タグ (深度、水温、3 軸加速度、位置情報を推定するための光レベルを記録する) を取り付けたいと考えていました。

As I looked outside the window of the Shinkansen, on my way back to the Seto Inland Sea, I was reminded of my first time seeing it approximately a year ago, also from a train, in September 2022, when I first went to Kaminoseki to collaborate with local fishermen in deploying miniPATs. That first trip, as I nervously looked out the train window, I had been struck with a sense of excitement; a feeling of the unknown – something new to be encountered. Now that I was in my second year, I had expected this feeling of unknown to be replaced by a feeling of familiarity. Although I now shared a connection with the sea, albeit a very small one compared to that of the people actually living and working there, there was still a sense of the unknown remaining. In fact, that feeling of unknown and mystery, as well as excitement, was even larger now. I had glimpsed the tip of the iceberg, sensed more tantalizing discoveries yet to be uncovered, from the data resulting from the miniPATs deployed the year previous.

瀬戸内海に向かう途中、新幹線の窓の外を眺めながら、約1年前、初めて瀬戸内海に行った2022年9月に電車の中から初めて見た時のことを思い出していました。 地元の漁師と協力してminiPATを装着するために上関へ初めて向かったとき、緊張しながら車窓の外を眺めつつ、何か新しいものに出会う予感に私は興奮していました。 2年目になった今、この未知の感覚は親近感に変わるだろうと期待していました。 しかし、私と海との関わりは、実際にそこで生活し働いている人々に比べるとはるかに小さく、まだまだ未知の感覚が残っていました。 実際のところ、その未知と謎、そして興奮は今の方がさらに大きくなっていました。 私は、前年に装着した miniPAT から得られたデータからエイの生態に関する氷山の一角を垣間見て、まだ明らかにされていない事実にさらに魅力的な期待を感じていました。

I was happy to return to the small port town where we based our research out of. In addition to fond memories of research and delicious fish, I enjoyed running along the road in front of the water during the rest time in our research (some little kids had randomly started running with me on one occasion). However, before indulging in sashimi or jogging with the energetic locals, there were preparations to do.

研究の拠点である小さな港町に戻ることができて、 研究とおいしい魚の楽しい思い出に加えて、研究の休憩時間に水辺の道を走るのがとても楽しかったです(小さな子供たちが偶然私と一緒に走り始めたことがありました)。 しかし、活気あふれる地元の人々と一緒にお刺身やジョギングを満喫する前に、やるべき準備がありました。

However, the preparations themselves were also interesting. To prepare for longlining, we cut the tails off of frozen horse mackerel, in order to make them easier to be swallowed by rays. As I cut off the tails on the wooden cutting board, I noticed that some of the stray cats enviously watching me were the kittens I had seen in my last visit, reminding me that some time had passed since I had last come. It was nice to smell fresh fish as I cut, and I remembered that the fresh smell had actually helped me, a very inexperienced sea person, from getting too seasick when I had first participated in longlining the previous year. We also sharpened the hooks for longlining, and made sure the lines were not tangled in preparation.

しかし、準備自体も興味深いものでした。 延縄の準備として、エイが飲み込みやすいように冷凍したアジの尾を切り落とします。 木のまな板の上で尻尾を切りながら、羨ましそうに私を見ている野良猫の何匹かが、前回訪問したときに見た子猫たちであることに気づき、最後に来たときから時間が経ったことを思い出しました。 魚を切るときに新鮮な魚の匂いを嗅ぐのがとても心地よく、前年に初めて延縄に参加したとき、その新鮮な匂いのおかげで海慣れしていない私が船酔いせずにすんだことを思い出しました。 延縄用の針も研ぎ、糸が絡まないように準備しました。

Finally, the long-awaited time for longlining arrived. I fondly remembered the leader fisherman grading my line-throwing abilities earlier (if throwing longlines were a class, I can confidently say that it was a course I failed multiple times, but thoroughly enjoyed). Considering my level had been rock-bottom, I thought that that meant there was only room for improvement, and thus was happy to be able to gain more experience again (inland in Kashiwa, I think I would cause confusion if I randomly started throwing longlines in the park).

いよいよ待ちに待った延縄の時期がやって来ました。 以前、漁師のリーダーが私の糸を投げる能力を採点してくれたのを懐かしく思い出しました(はえ縄を投げるのが授業だとしたら、何度も失敗しましたが、とても楽しかった授業だと自信を持って言えます)。 自分のレベルがどん底だったことを考えると、まだまだ伸びる余地はあると思っていたので、また経験を積めることができて嬉しかったです(もし私が柏の公園で、やみくもに延縄を投げる練習をしたら、きっと周りの人々の混乱を招いたことでしょう)。

Despite our mental preparations for potentially not catching any rays, on our first longline, we successfully caught and tagged two rays, and over the course of the next two days, successfully caught and tagged another three. The first ray was the largest pitted stingray I had yet seen, and in fact, was the largest fish I had ever seen in my life in the wild. It was approximately two meters in disc width, and had a beautiful black spot, almost perfectly round, at the base of its tail. It was my first time seeing this kind of marking, too. Although difficult to maneuver due to its large size, the area of musculature at the tail base was ample, and I was able to securely attach the tag to the ray. In this way, we were able to successfully deploy the same number of miniPATs as the year previous. This reminded me that each time I am blessed with the opportunity to experience field research, I experience new things.

もしかしたら、エイを捕まえられないのではないかと心配していたにもかかわらず、最初の延縄で2匹のエイを捕まえてタグを付けることに成功し、その後の2日間でさらに3匹のエイを捕まえてタグを付けることができました。 最初のエイは私がこれまで見た中で最大のアカエイで、実際、私がこれまで野生で見た最大の魚でした。 円盤の幅は約2メートルで、尾の付け根には、これまで見たことがないほぼ真円の美しい黒い斑点がありました。体が大きいため操作は難しいですが、尾の付け根の筋肉組織が十分にあり、タグをエイにしっかりと取り付けることができました。 このようにして、前年と同数の miniPAT を導入することができました。 フィールド調査を経験する機会に恵まれるたびに、新たな発見があることを改めて感じました。

Thankfully, although I nervously checked the ARGOS satellite website for any notification of a detached tag, no signals arrived, indicating that all tags were still securely attached to their host rays (miniPAT data loggers send out signals to a satellite, which are then sent to a website, when they have detached from their host rays and floated to the sea surface). Like the year previous, this trip was successful, and I also was able to explore Kaminoseki during the rest time. Thus, I was able to head back to Kashiwa with many scenic photos of the Kaminoseki area (and delicious fish in my stomach). Furthermore, compared to last year’s survey, where one tag was unfortunately detached from the fish, this year no signals have been detected as of the writing of this report, indicating that all tags are still successfully attached to their rays. I hope for more interesting data from the five rays newly tagged after eight months.

I would like to express a deep thank you to all of the members of this pitted stingray team.

ARGOS 衛星 Web サイトでタグの切り離しに関する通知がないか神経質にチェックしましたが、嬉しいことに信号は発信されていませんでした。これは、すべてのタグがまだ魚にしっかりとついていることを示しています (miniPAT データ ロガーが魚から切り離されて海面に浮かぶと、信号を衛星に送信し、その信号が衛星に送信されるのです)。昨年同様、今回の旅も無事に終わり、休憩時間には上関を散策することもできました。 こうして私は、上関地域のたくさんの美しい写真(そしておいしい魚をお腹に)を抱えて柏に戻ることができました。昨年の調査では、残念ながら1つの装置がすぐに外れてしまいましたが、今年はこのレポート執筆時点で信号は検出されておらず、すべてのタグがまだ正常に魚に付いていることが確認できています。8ヶ月後に装置が魚から切り離されて興味深いデータが送られてくることを期待しています。 調査チームの全員に深く感謝しています。

Additionally, in this biologging fund, I would to thank you for your generous donations which aid in enabling the continuation of research such as this.

さらに、このバイオロギング基金サイトを通して、このような研究の継続を可能にするために多大なご寄付をいただきましたことに深く感謝いたします。

カナダ東海岸における巨大マグロの行動調査

2023年11月15日(水)

吉田誠(東京大学大気海洋研究所・特任研究員)

私は佐藤研究室で2017年に学位を取り、2018年から5年間、国立環境研究所のポスドクとして琵琶湖で淡水魚の回遊研究に取り組んだ後、今年の4月から再び東大に戻ってポスドクをしています。今回は日本とアメリカの共同研究で、2023年9月下旬から10月初頭にかけて巨大マグロのバイオロギング調査に行ってきました。場所はカナダの南東部、大西洋に突き出したノバスコシア半島の東端にあるケープブレトン島です。この島は、五大湖から大西洋への湖水の出口にあたるセントローレンス湾の南に位置しており、島の北西側がセントローレンス湾、南東側が大西洋に面しています。ケープブレトン島を含むノバスコシア州は漁業の盛んな地域で、アメリカンロブスターの一大産地として有名なほか、ズワイガニやタラ、ニシンなどの冷水性の魚介類も多く水揚げされます。また、セントローレンス湾はタイセイヨウニシンの主要な産卵場として知られ、夏〜秋季には産卵のため来遊するニシンを狙って、海鳥、アザラシやクジラなどの捕食者が湾内に多く集まります。今回の調査対象であるタイセイヨウクロマグロもこの一員で、体長3メートル、体重400キログラムにも達する超大型の個体がこの水域に多く集まることから、巨大マグロを求める漁業者・釣り人にとっても非常に良い漁場となっています。

ところで、「タイセイヨウクロマグロ」という見慣れない表記に違和感を覚えた方がいるかもしれません。実は、大西洋に分布するタイセイヨウクロマグロ(学名:Thunnus thynnus)は、私たちがスーパーマーケットや寿司屋で「本まぐろ」の名前で目にするクロマグロ(学名:Thunnus orientalis、太平洋に分布)とは別種だと考えられています(このため、英語では前者を“Atlantic bluefin tuna”、後者を“Pacific bluefin tuna”と呼び分けます)。タイセイヨウクロマグロはクロマグロと比べてより大きく成長することが知られ、これまでに記録された最大の個体は全長4.6メートル、体重680キログラムにも達します。まさに「巨大魚」と呼ぶのにふさわしいこのタイセイヨウクロマグロは、国際的な水産資源としても非常に重要な魚種ですが、高級食材としての需要の増大とそれに伴う乱獲により、個体数が急激な減少傾向にあります。このため、タイセイヨウクロマグロを将来にわたって持続的に水産資源として活用するには、科学的知見に基づく資源管理(漁獲量の管理)が必要です。このような背景のもと、セントローレンス湾では2006年頃から、米国スタンフォード大学のバーバラ・ブロック教授らのチームにより、タイセイヨウクロマグロにアーカイバルタグと呼ばれる移動経路の記録装置を取り付ける追跡調査が長期にわたりおこなわれてきました。これにより、タイセイヨウクロマグロの2大産卵場であるメキシコ湾・地中海のどちらで生まれた個体も、数千キロメートル離れたセントローレンス湾に来遊し、豊富な餌を食べて大きく成長した後に再び、自らの生まれた海域(メキシコ湾または地中海)まで産卵のために戻ることが明らかとなりつつあります。

このように、セントローレンス湾はタイセイヨウクロマグロにとって重要な採餌海域ですが、人間による漁業も盛んに行われており、マグロに対して様々な人為的影響が及んでいると考えられます。たとえば、マグロを狙って多数の漁船(釣り船)が集まることによる過度な漁獲圧(乱獲)や、スポーツフィッシングで行われているキャッチアンドリリース行為のもたらす悪影響も懸念されています。一方で、ニシン漁船からの投棄物(傷ついたニシンや混獲された他魚種等)を目当てにマグロが漁船の周囲に集まる様子もたびたび観察されています。こうした人間活動がマグロの採餌行動や栄養状態、その後の回遊行動に及ぼす影響を正確に知るためには、これまで蓄積されてきた回遊データだけでなく、湾内での詳細な行動データも必要となります。そこで今回、日本のバイオロギング機器メーカー(リトルレオナルド社およびバイオロギング・ソリューションズ社)が開発した最新鋭のビデオロガー(動物搭載型の小型水中ビデオカメラ)と行動記録計(速度・加速度・地磁気ロガー)をマグロに取り付けるべく、私と大学院生の松田くんの2名でカナダへ向かうこととなりました。

現地では、バーバラ、ロビー、テッドの3名と私たち日本人2名をコアチームとし、それに加えてバーバラと親交のあるマグロ釣り師や、地元の大学から来た研究者とその学生たちが入れ替わりで参加する形で日々の調査が行われました。1日の流れはシンプルで、早朝6時に出港して日中はひたすらマグロ釣りとタグ装着、日没前後の夜7時〜8時に釣りを終えて帰港します。この海域のマグロ釣りではニシンやサバを丸一匹使ったエサ釣りが基本のため、マグロの居そうな地点で船を止めて針を投入したあとは、マグロが針にかかるまでひたすら待ち続けることになります。待ち時間の過ごし方は人それぞれで、キャビンあるいはデッキ上で誰かと話したり、携帯スピーカーで音楽をかけたり、退屈してきたらデッキの適当な場所で横になって昼寝をしたり……。かくいう私は、海での乗船調査が初めてだったこともあり、なんとしても船酔いになるまいとひたすら遠くを見つめて座っていることがほとんどでした。一方、松田くんは日本でのカジキ調査で鍛えられているためか顔色一つ変わる気配もなく、エサの追加調達のためにサビキ釣りをするテッドや船員のショーンを手伝ったり、日本で撮りためたカジキの写真や動画を見せながら釣り師と熱い魚トークをしていたりと、早々にチームの一員として溶け込んでいたのが印象的でした。

マグロが針にかかった瞬間、船上に漂うなんとものどかな雰囲気は一瞬にして吹き飛びます。

「ジーィィィィィッ!!」とけたたましい音を立てつつ、リールから飛ぶように引き出されていく極太の釣り糸。釣り竿に取り付き、巨大なリールを抱え込んで糸を巻き取ろうとする釣り人。バタバタと持ち場に走り、必要な道具の準備を始めるチーム各員。そして毎回必ず、自信に満ちた表情で「This is a big fish!!!(これは大きい魚だ!)」と叫ぶバーバラ(意図はよく分かりませんが、チーム全員を鼓舞したかったのかも?)。そこからは、圧倒的なパワーではるか水平線まで泳ぎ去ろうかというマグロの強烈な引きに対し、船をマグロと同じ方向に走らせながら徐々に糸を巻き取っては、糸を再び引き出されて、の繰り返し。マグロの体力をジリジリと削り、船の間近に寄せるまでには短くても30分、長いときには1時間半もかかります。一進一退の激闘の末、ようやく抵抗しなくなったマグロを船に引き上げる段階になると、そこからは打って変わって全ての作業が迅速に進みます。まず船尾のドア付近にマグロを寄せ、口にロープ付きの手鉤(てかぎ)を引っかけたら、綱引きの要領で5-6人がかりでマグロをデッキに引き上げます。マグロを濡らしたマットの上に横たえ、口にホースを差し込んでえらに海水を通すと同時に、両眼を濡れタオルで覆います(こうするとマグロが暴れない)。技術員のテッドがすかさずマグロの体長を測り、DNA解析用にひれの端を切り取ってチューブに保存。その傍ら、タグ取り付け用の銛を手にしたバーバラは、ロビーの手を借りながらマグロの背中に次々と機材を取り付けていきます。タグ装着が終わるや否や、マグロの乗ったマットをこれまた5-6人がかりで持ち上げて向きを180度入れ替え、船尾のドアからマグロを海中にすべり込ませるように放流して作業完了となります。マグロを引き上げてから放すまではわずか2分間という驚異的な作業スピードで、世界トップクラスの研究者(チーム)の洗練された手技手法をこうして目近で見られたことは実によい勉強になりました。

私たちが今回マグロに取り付けたロガー(ビデオロガーと行動記録計)はどちらも、データをロガー内部に記録します。そのため、データを得るにはロガー本体を回収する必要があります。そこで、2台のロガーと衛星発信機を樹脂製のフロート(浮き)に埋め込んでひとまとまりのタグを作り、タイマー式切離し装置を使ってマグロの体にとりつけました。これにより、装着から1-2日後にタイマーが作動し、タグのみがマグロから切り離されて海面に浮上するため、あとは衛星発信機の出す電波をたよりに船でタグを探して回収できます。……とは言ったものの、実際のところ、3個体分のタグの回収作業はどれも一筋縄では行きませんでした。中でも、1個体目のマグロから切り離されたタグは放流地点からなんと100キロメートルも離れた地点に浮上し、しかも潮流に乗ってかなりの速さで北西(セントローレンス湾から大西洋へ出る)方向に流されていたため、ケープブレトン島の西側にある我々の拠点から船で追いかけていては間に合いません。そこで、翌日の早朝に島の北端部の港まで車で3時間かけて移動し、現地で漁船をチャーターして出港、2時間あまりの捜索の後、タグが大西洋に出て行く直前になんとか回収することができました。残る2個体分も、チャーター船があまりに遅すぎて往復3時間以上も船上で過ごす羽目になったり(タグ自体は現場到着後すぐに見つかりましたが)、タグが近くに浮いているはずなのに信号が全く入らず2-3時間も現場で右往左往したりと、これまでに経験したことのない出来事の連続でした。フィールド調査では、現場の状況に応じた臨機応変さと、予期せぬ事態に出会っても動じない強い心が大事だと言われます。私自身、似たようなことを色々な人から聞かされていましたが、今回の体験を通じてこれらの言葉があらためて身にしみました。

結果として今回の調査では、タイセイヨウクロマグロ3個体から計78時間の行動データおよび計15時間の映像データを得ることができました。日本に帰国してすぐにおこなった予備的な解析では、直線的に移動していたマグロが時折、特定のごく狭いエリア内に留まってウロウロするような行動がみられたり、マグロ視点の水中映像に他個体が映り込んだりと、湾内での採餌行動に関連するとみられる興味深い結果が得られ始めています。今後はこれらのデータの詳細な解析を進め、マグロ研究の第一人者・バーバラとのディスカッションも深めながら、世界最大級のマグロの未知の行動・生態を明らかにできればと考えています。

来年のカレンダーできました

2023年11月10日(金)

佐藤克文(東京大学大気海洋研究所・教授)

バイオロギング研究会で毎年作っているカレンダーができあがりました。年1万円の継続会員の皆様および3万円以上をご寄付いただけた方にまもなくお送りいたします。

来年3月4日から8日にかけて、東京大学で第8回バイオロギング国際シンポジウムを開催いたします。9日には高校生・大学生向けの講演会も予定しております。

人工衛星発信器をつけたウミガメが旅立っていきました

2023年08月25日(金)

佐藤克文(東京大学大気海洋研究所・教授)

岩手県大槌町にある東京大学大気海洋研究所附属大槌沿岸センターでは、大学院生のウミガメ班が滞在し調査を続けています。多くの皆様から多大なご寄付をいただいたおかげもあり、今年は人工衛星発信器を10台用意することが出来ました。一覧表にある通り、計10頭のウミガメに発信器を取り付けて放流しました。

藻類をたべるために沿岸付近を回遊すると言われているアオウミガメ(839)が岸寄りを泳ぐのは予想どおりなのですが、例年に比べて今年はアカウミガメで沿岸付近をウロウロする個体が多い印象を受けます。そのせいかこれまで既に10頭の内2頭のアカウミガメが再び漁具によって捕獲され,残念ながら死亡してしまいました。クロウミガメ(840)はアオウミガメに似た動きをしているように見えますが、クロウミガメに発信器をつけたのは今回が初めてなので、今後の動きが気になります。

今年もウミガメ調査が始まりました

2023年07月07日(金)

佐藤克文(東京大学大気海洋研究所・教授)

暑い夏が始まりました。皆様は如何お過ごしでしょうか。私は岩手県大槌町にある東京大学大気海洋研究所附属大槌沿岸センターに7月3日から来ています。一足先に大槌入りした大学院生たちにより、毎年恒例のウミガメ調査が既に始まっています。私の大槌入りを歓迎するかの如く、早速今朝アカウミガメが一頭付近の定置網で捕獲されました。大学院生によって手際よく体長測定がなされ、標識が付けられました。

今日は調査に協力してくれている付近の定置網漁業者の方々に挨拶に行ってきました。今年の5月5日の朝日新聞の折々の言葉という欄で、「お酒もうれしいけど、俺たちが持ってきたカメで何がわかったのか知りたいなあ by 岩手県の一漁師」という言葉が紹介されました。これは、当研究室の卒業生である木下千尋さんが発信した情報が取り上げられたものです。木下さんはイラスト入りの本で動物たちの生態を紹介しています。今日は漁師さんにその本を手渡してきました。もちろん一升瓶も一緒に。

昨年までのウミガメたちの回遊経路をご紹介します。一昨年度(2021年)の夏に人工衛星発信器をつけて岩手から放流した395番(日本スピンドル2号)は、何と1年半も追いかけることができました。最後の通信日は2023年1月23日でした。高知から放流した1頭(398信ちゃん)は2022年12月19日が最後の受信となりました。この個体(398信ちゃん)は高知を出発した後、九州の西側の東シナ海に回遊し、そこで1年近く滞在して潜水を繰り返していました。よほど美味しいもの、おそらく大陸棚上の底生動物を食べていたものと想像されますが、それを検証するための実験を近い将来やりたいと思っています。

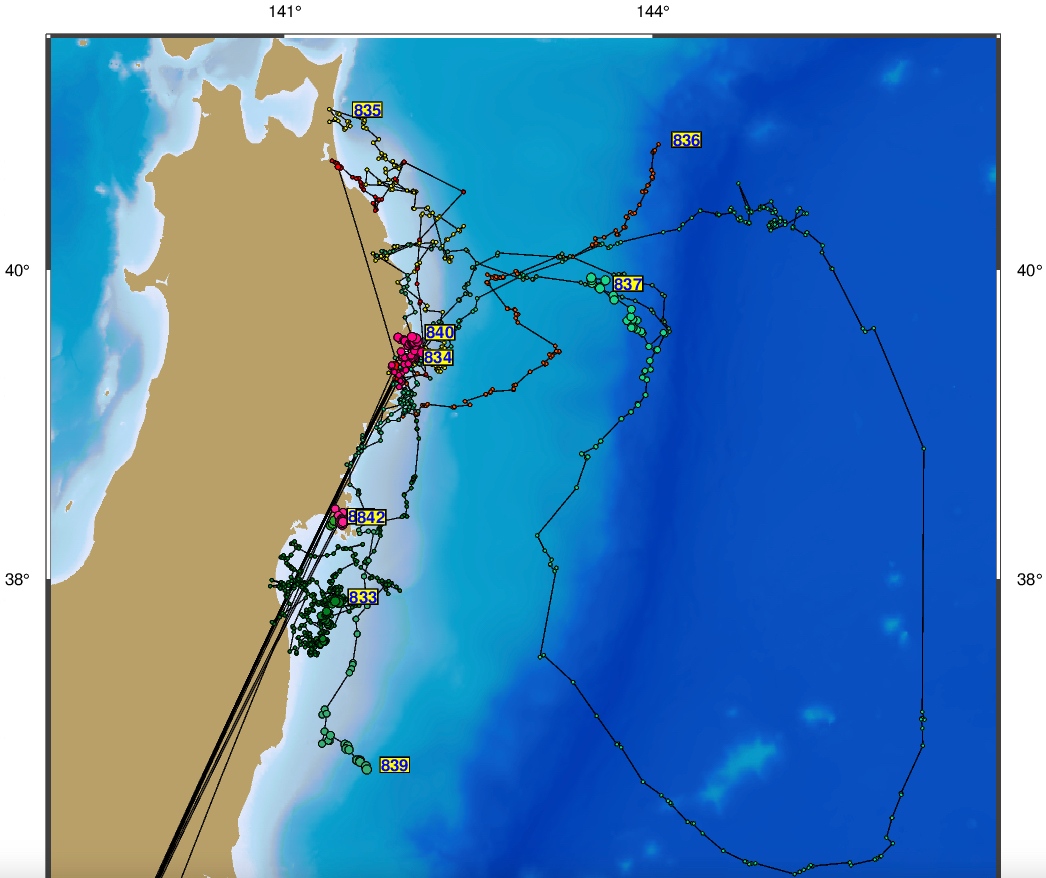

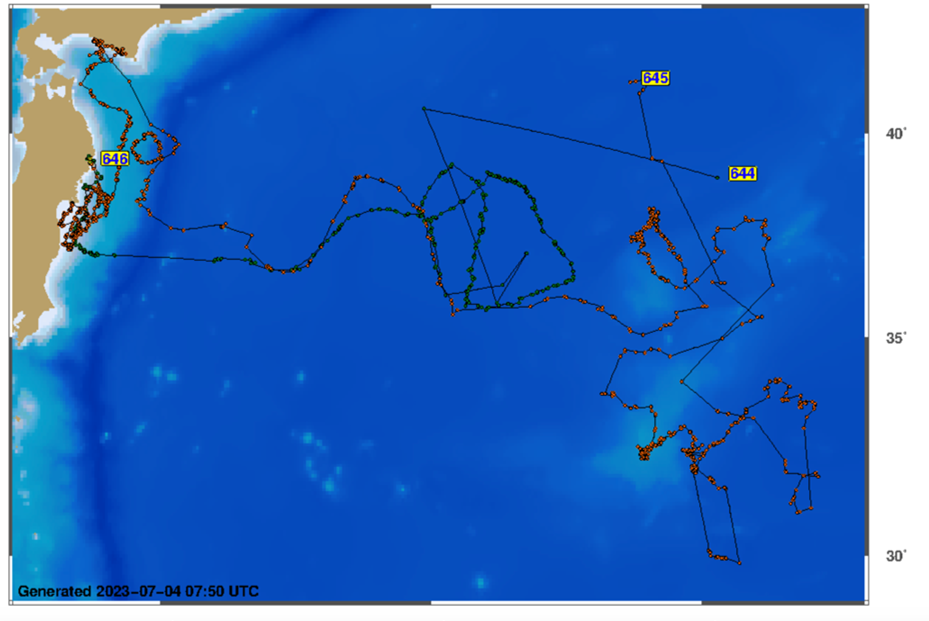

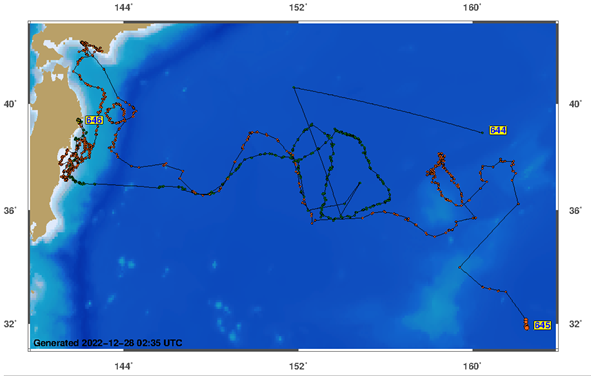

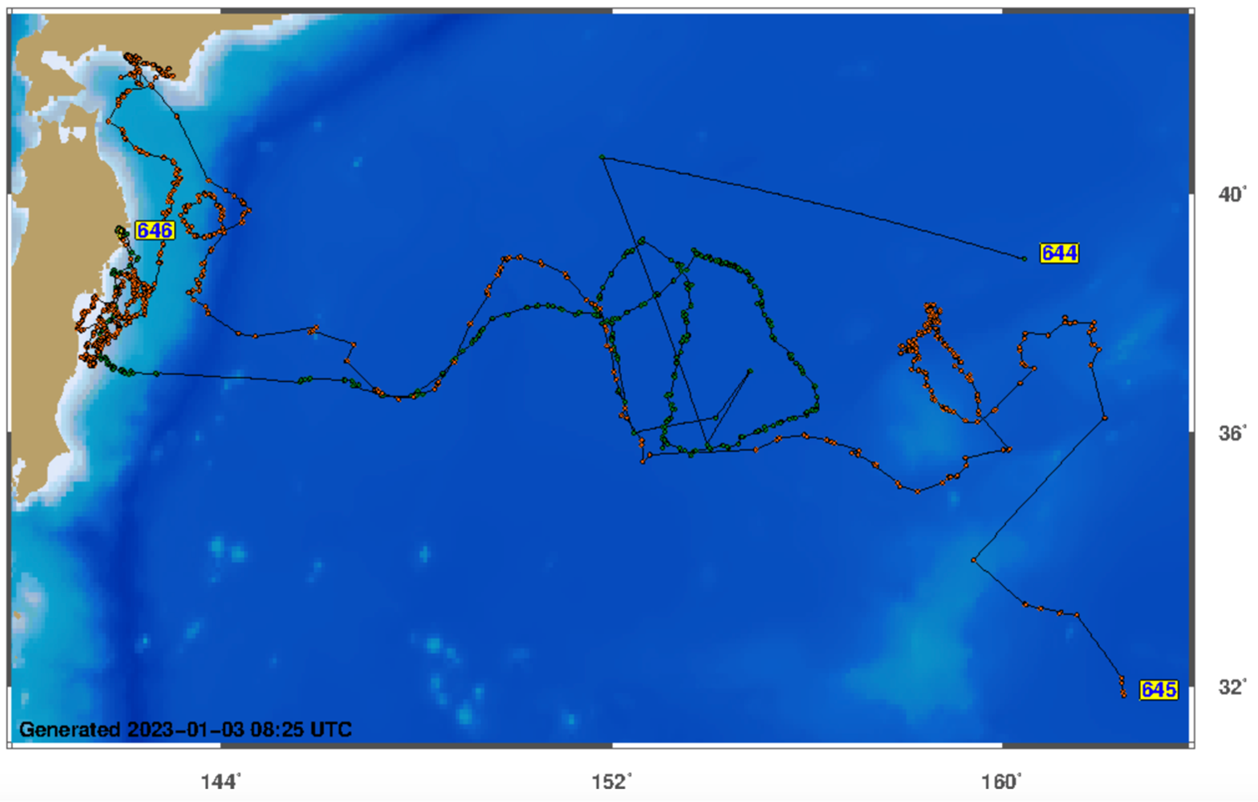

2022年の夏には3頭のアカウミガメ(644, 645, 646)に人工衛星発信器をつけて岩手から放流しました(下図)。内1頭(646)は放流直後に定置網に引っかかって死亡した模様で、通信が途絶えました。残る2頭は外洋に向かって泳いでいきました。1頭(644衣織ちゃん)は11月20日に最後の通信があった後、通信が途絶えています。電池寿命は1年間なので、電池がなくなるにしては早すぎます。もしかしたら、良くないことが起こったのかもしれません。もう1頭(645衣知花ちゃん)は2023年6月27日に最後の通信がありました。快調に大海原一人旅を続けている模様です。いったいどんな暮らしをしているのでしょう? 645衣知花ちゃんの潜水行動をみると、今年に入ってからは水面にいる時間が長いようですが、時々深度100mにまで潜っています。いったい何をしているのでしょう?電池寿命に達する2023年夏まで経路を追い続けます。

皆様のサポートのおかげもあり、今年度は合計10台の人工衛星発信器を用意することができています。発信器が取り付けられたウミガメたちがこれから続々と放流されます。是非とも皆様名前を付けてあげて下さい。

寝坊したら 200万円?!

2023年06月01日(木)

呂律(東京大学大学院新領域創成科学研究科自然環境学専攻・博士2年)

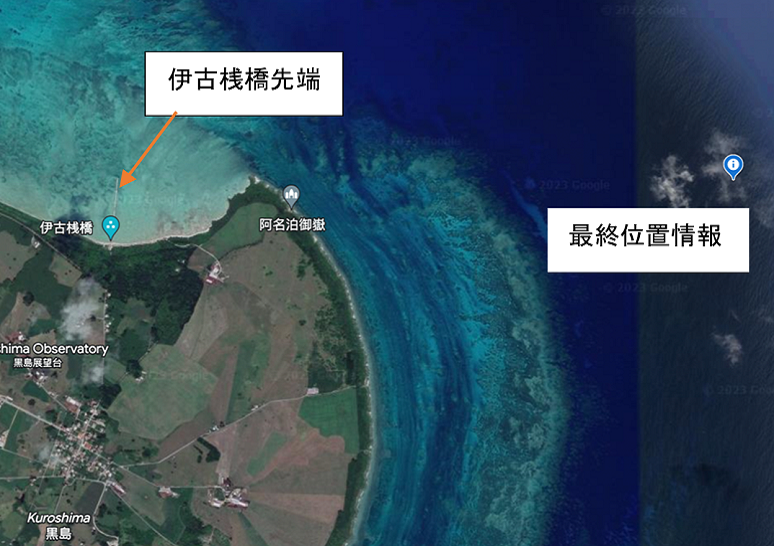

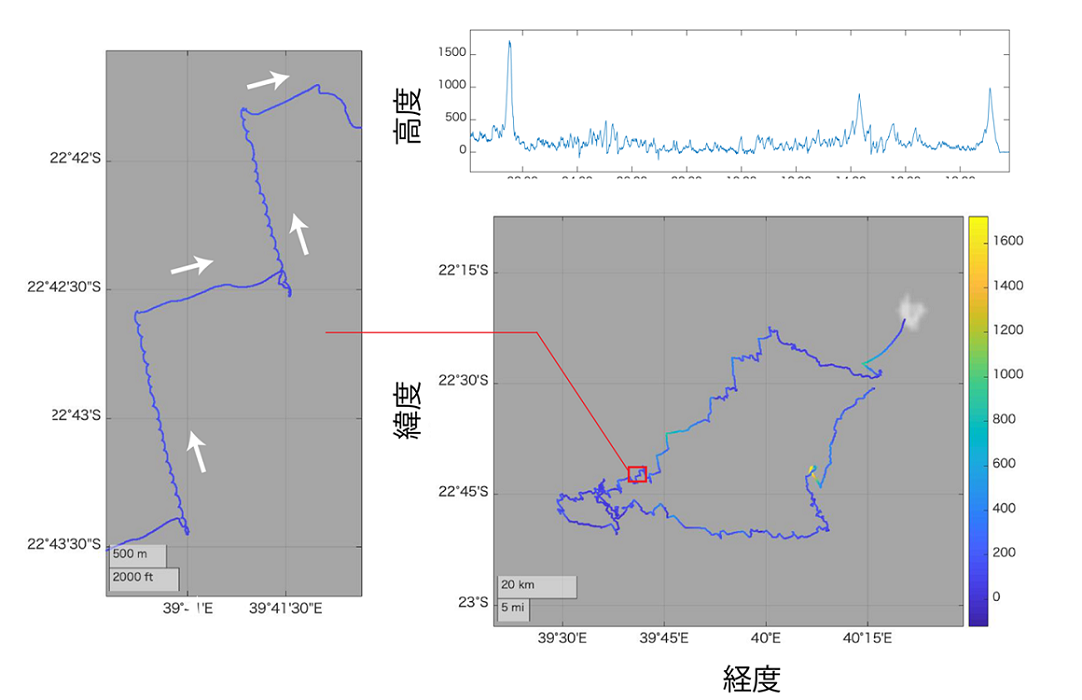

昨年夏に沖縄県黒島で行った調査によって得られたデータから興味深い行動が見つかり、同時に黒島研究所の研究員から「夏のウミガメはサンゴ礁内で生活しているけど、冬はサンゴ礁内の水温が下がるため、ウミガメはサンゴ礁の外に出る傾向がある」と聞きました。好奇心旺盛な私たちは、冬季に黒島周辺のウミガメから行動データを取ることを計画し、2023年の2月から3月にかけて、今年最初のフィールド調査として沖縄県黒島に行ってきました。

黒島は南国の島ですが、夏との違いがはっきり感じられました。草の丈は低く、たくさんの花が咲き、意外と低い気温、そしてかなり強い風が吹いていました。ダウンジャケットを持って行かなかったのは大失敗でした。現地入りしてから早速実験用のウミガメを捕獲しに行きました。刺し網を沿岸に設置した後、網に引っ掛かったウミガメが溺死しないようこまめにチェックするために海に入るので、冷たい海水と強い北風に耐えるのに、体力と気合いの両方が必要でした。2回刺し網を仕掛け、その間12回海にはいり、黒島研究所のスタッフにサポートしてもらいながら16個体を確保することができました。

昨年夏の放流経験を参考に、2頭のウミガメに浮力体(図1)を付けて放流し、2セットを同時回収する準備を進めました。しかし、効率良くデータを取りたいと願う私達に対して、厳しい現実が突きつけられました。2月11日朝7時に調査用浮力体がウミガメの甲羅から切り離されて海面に浮かぶように設定したのですが、浮力体につけた発信器からの信号は受信されず、半日経っても何も情報が得られません。1セットの浮力体には合計5つの記録計(ロガー)が装備されているので、合計10個のロガー(ほとんど持って行ったすべての実験装置)が最初の実験で失われたことになります。ウミガメが岩の間や洞窟の中に潜り込んで休んだために切り離し用のワイヤーが断線してしまったのか、タイマーが故障して機能しなかったのか、浮力体を甲羅に装着する際に気がつかぬまま何かミスをやらかしてしまったのかなど。ありとあらゆる原因が頭をよぎりましたが、2セット両方が浮かんで来ない状況では、失敗した理由を特定することはできませんでした。その時得た教訓は、上手くいった前回から何か少しでもやり方を変更する場合、予めテストするのはもちろん、最初は保守的に1頭から実験を始めた方が良いというものです(指導教員「はい、是非そうして下さい」)。調査が始まったばかりなのに、ロガーが無くなってしまい放流実験を継続できないという深刻な問題が発生し、諦めてデータゼロのまま柏に戻るか、リスクを冒して研究室に必要な機材を送ってもらって2回目の実験を行うかを判断せざるをえない状況になってしまいました。私は非常に楽観的な人間なので、何らかの理由でロストしたロガーはいつか回収されると信じていました。したがって、装置が浮かんでくるのを待ちながら、さらなる実験ができるように追加の機材を送ってもらうことを考えていました。私の極端な楽観的性格のおかげで、目の前の海の何処かに400万円と貴重なデータが漂っていることは分かっていたのですが、なぜだか平常心で過ごすことができました(指導教員「ひー、それを知っていたら私は平常心ではいられませんでした」)。

失敗した原因が分からないまま次の放流実験を強行するのはあまりに無鉄砲な行為だと思い、当初の予定通り柏に戻る航空券を予約しようとした19日のことです。朝起きてご飯を食べながら信号の受信チェックをwebサイトで行ったところ、黒島の北側に白い点が1つ増えているように見えました!(図2)。その瞬間、頭の中で花火が打ち上がりました。詳細を確認するためにその白い点をクリックしたら間違いない、まさしく私達が待ち続けていた浮力体からの信号でした。いつもの様に船で回収出来ると思ったのですが、海が荒れて船が出せません。なすすべもない8時間を過ごした後、とりあえず最終位置情報は島周辺の北東方向を示していましたので(図3青いマーク)島北部にある伊古桟橋に(300メートル海に延びる突堤)に行き、手持ちの受信機で探索してみることにしました。北風が吹いているから、もしかしたら浮力体が岸まで流されてくるかもしれないという可能性にかけたのです。桟橋の先端に行っても信号の受信状況は不安定で、なかなか発信器の方位を出すことができませんが 時々岸側から受信が来ました。あきらめて帰る前にダメもとで岸沿いに歩きはじめたところ、十何メートルの先にピンクの浮力体が横になっているではありませんか(図4)。とうとう21:13に装置を回収することができました。この経験を通して、重要な教訓を得ることができました。「簡単に諦めないこと。どんな不味い現状に置かれても、状況をふまえながら他の計画を準備すること。希望を持ち続けること。なぜなら人生は驚きや不思議に満ちているものだから」。

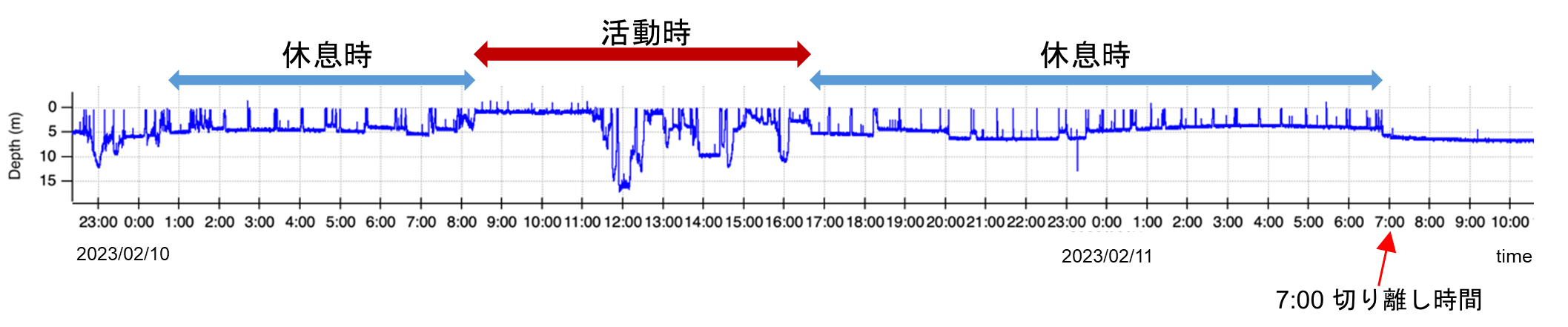

回収後検査したら浮力体やロガーに明らかな損傷はなく、予定通りタイマーは起動して装置はウミガメから切り離しされたことがわかりました。だとしたら「なぜ浮かんでこなかった?」のだろう。その原因はウミガメから得られた行動データの中に隠れていました。ウミガメは冬に寝坊をしていたのです。なんと面白く、驚くべきかつ合理的な理由でしょう。夏に得られたデータによると、ウミガメは朝6時頃から動き始める傾向がありました。ところが、図5を見て下さい。

冬には更に2〜3時間眠り、8時頃になってようやく起きて動き始めていたのです。夏に実験をした時は、朝7時にタイマーを起動させて装置をウミガメから切り離すことで、海面に浮かぶ装置を易々回収することができました。ところが、冬に7時にタイマーを設定してしまうと、ウミガメがまだサンゴや岩の下で眠っている時に装置が切り離されてしまうため、水面まで浮かぶことがなく、だから信号も受信できなかったのです。その後は、切り離し時間を9時に変更し、更にワイヤーの保護も強化したところ、残る4回の放流実験では、すべての装置をスムーズに回収することができました

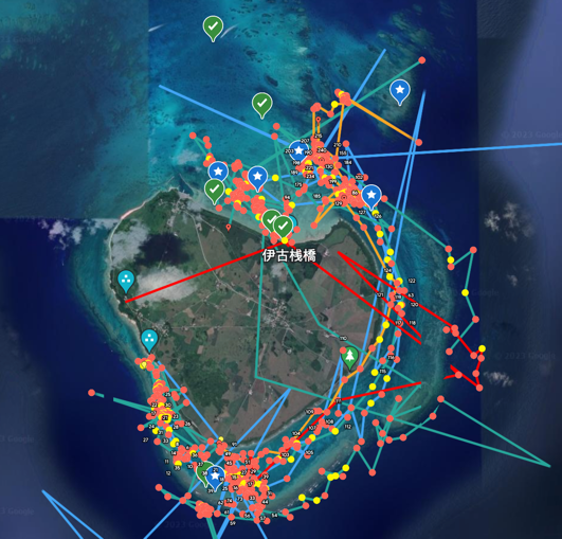

今回3個体から取れたデータをまとめて見たところ、目覚め時刻が夏よりも遅いということの他に、サンゴ礁内の自分の「なわばり」範囲内にとどまることがわかりました。今回、オクダ海域(図6赤い丸)で捕獲された3匹のウミガメから切り離された浮力体がオクダ海域に浮かんでいたのに対し(黄色のマーク、岸から徒歩で回収)、去年夏の2頭(オクダ海域)の浮力体は北に少し離れた沖のところに浮かんでいました(青いマーク、船で回収)。黒島周辺のアオウミガメが「なわばり」に戻ることが分かってきました。そこでどこまで自分のなわばりに固執するのかを調べるために北に捕獲したカメを南に、南で捕獲したカメを北に移送してから放流しました。その結果、興味深いことが下の図7から分かってきました。5個体のウミガメが泳いだ経路を表す線が常に島の東側にあるように見えます。つまり北から南へ戻るウミガメも、南から北へ戻るウミガメも、なぜか黒島の東側を好んで泳ぎ通って生息域に戻っていたのです。いったい何が、ウミガメの帰還行動に影響を与えるのでしょうか。2年間のデータだけでは本当にこういう傾向があるとは言い切れません。長期的なかつ継続的なモニタリングと実験をしないと、多くの神秘的な行動の裏にある興味深いメカニズムを明らかにすることはできません。

野外調査を実施するためには、好奇心、情熱、努力だけでなく、装置を購入する資金も必要です。このような素晴らしいフィールド調査をサポートして下さった全てのスポンサーの皆さんに心から深く感謝します。

初めて経験したウミガメ調査

2023年05月01日(月)

黒田健太(東京大学大学院農学生命科学研究科水圏生物科学専攻 修士2年)

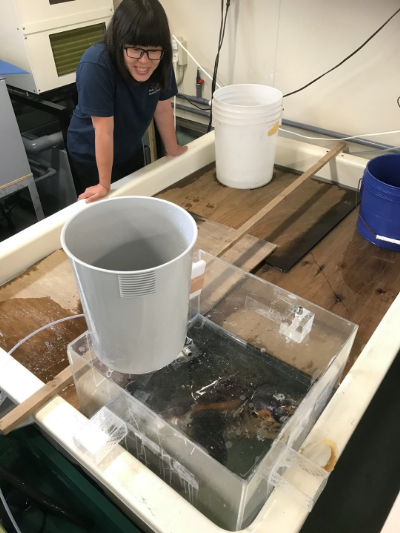

皆さん、こんにちは。大気海洋研究所 修士課程2年の黒田です。私は2022年の7~9月の間、岩手県大槌町にある東京大学大気海洋研究所付属の臨海施設で、ウミガメの調査を行いました。この調査は2005年以降、毎年夏に私が所属している研究室で継続してきたものです。目的は主に三つあり、①7~9月にかけて三陸沖で捕獲される野生のウミガメのモニタリング、②それら野生のウミガメを用いた水槽での実験、③それら野生のウミガメにロガー(小型記録計)を装着し野外放流する、というものです。

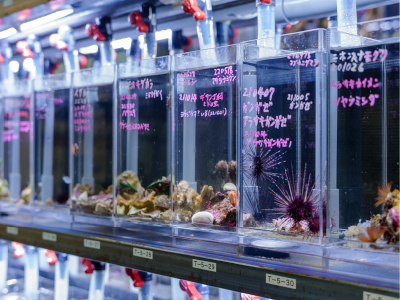

調査地には先輩学生と指導教員の自家用車2台で向かいました。私は関東以北に行ったことがなく、研究室がある千葉県を出発し、茨城県を過ぎてからは黒田の到達北限を更新しながら進んで行きました。そして次の日から、3ヶ月間のウミガメ共同生活が始まりました。我々三陸ウミガメ研究チームの一日は、地元の漁師さんたちのモーニングコールから始まります。我々は、地元の定置網漁場で魚と混ざって捕獲されたウミガメを、漁師さんたちから譲り受けて研究で使っています。あらかじめウミガメチームの代表学生の連絡先を漁師さんたちにお渡ししているので、ウミガメが混獲されていれば、朝早くに漁を終えた漁師さんたちから電話がかかってきます。ちなみに男女それぞれ1名の連絡先をお伝えしてあるのですが、必ず女性学生の携帯電話が鳴ります。そして軽トラを走らせ漁場に向かい、荷台にウミガメを乗せ臨海施設まで帰った後は、すぐにそれぞれの個体情報を記録し、モニタリングデータとしてアーカイブ化します。実は、私黒田は、今まで動物を飼ったり、世話をしたりしたことがなく(小学校の頃、ウサギ当番サボりの常習犯でした)、間近に感じる動物の息づかいに戸惑いと強い感動を覚えました。ウミガメの個体情報の記録が終わったら、ウミガメを臨海施設の水槽に入れ、飼育します(下図)。

実験設定に見合う個体がいれば、彼らの心拍数や呼気を測定したり、錘を取り付けたりなどの水槽実験を行いました(下図)。

2020年、2021年と2年連続でウミガメが少ししか捕れなかったのに対し、2022年は3ヶ月間で70匹程度捕獲され、多くのデータを集めることが出来ました。そして、我々バイオロギング研究従事者にとって最も重要な野外放流実験も複数回行いました。ウミガメに各種ロガーを取り付け海に放し、数時間~数日後に切り離されるロガーを船で回収する、あるいは数年かけてデータを集めモニタリングするという内容です。(黒田はこの時生まれて初めて船に乗りましたが、自分がとても船酔いしやすい体質だと分かりました。) 私も最新のロガーをウミガメに取り付け、数時間の放流実験を行いました。台風の影響で実験できるかどうかが危ぶまれましたが、実験日当日は天気も良く、先輩学生や共同研究者、船舶職員の方々の協力もあり、無事データを得ることが出来ました。調査生活はとても充実したものだったと思います。

また、長期調査の醍醐味は研究そのものだけではありません。休みの日には毎日釣りをして(下図)、釣った魚を自分で捌き、自分で食べる。三陸の豊かな海がもたらす新鮮で美味しい魚介類を毎日、自分たちで捌いて自炊をしていたため、料理と味利きのレベルが格段に上がりました。また普段は威厳のある教授陣たちも、晩酌時には下町のへべれけおじさんよろしく千鳥足で歩き、研究室にいる時とのギャップに大笑いしました。

調査地での3ヶ月間は、長くも短いもので、気付けばあっという間に最終日になっていました。最後は先輩学生の車で研究室のある千葉まで帰りました。車窓の中で、見慣れた漁港や岩手のローカルストアの並ぶ景色が後ろへ遠ざかっていくのを見て、少し寂しい気持ちになりました。この3ヶ月間は、私の人生の中でもひときわ楽しく刺激的で、そして自分を大きく成長させてくれるものでした。

A field trip to Taiji 和歌山県太地町への調査旅行

2023年04月20日(木)

呂孟樺(東京大学大学院新領域創成科学研究科自然環境専攻・修士2年)

It was a long trip from Kashiwa to Taiji. I woke up at 4 AM to catch the first train heading to the airport. The view changed suddenly from downtown to seaside at the moment I stepped out the airport. There were no tall buildings but the azure sky and distant sea level. On the way driving to our destination- Taiji whale museum- we passed through a local attraction called Hashigui-iwa Rock, a landscape formed by magma (Figure 1). The rocks were like a barrier, standing between me and the waves. The tide retreated. I bended down, staring at the rocky shore and a small tidal pool. The last time I saw such view was probably 3 years ago. I missed all of these, the salty breeze, the splashed waves, and the tiny world in the intertidal zone.

和歌山県太地町までは本当に長い旅でした。まず、空港に向かう始発電車に乗るために、午前4時に起きました。和歌山県の白浜空港を出たら、景色が都心から海へと一変してました。高い建物はなく、紺碧の空と遠くの海面だけがありました。目的地である太地くじら博物館に向かう途中、マグマによって形成された景観である橋杭岩と呼ばれる地元の名所を通過しました(図1)。岩は私と波の間に立ちはだかる障壁のようでした。潮が引いた後、私は腰をかがめ、岩場の小さな潮だまりを見つめました。このような景色を最後に見たのは、おそらく3年前のこと。潮風、波しぶき、潮間帯の小さな世界、これらすべてが恋しかったです。

That was a fresh start for this field trip, you may say, but it was certainly not compared to what has about to come next. A dozen of dolphin swim around the bay connected to the museum. They were the reason of this field research – we were going to measure their resting metabolic rate using a flow cup and a heart rate logger. After settling down the equipment and tomorrow’s schedule, I had a wonderful dinner and fell into a peaceful slumber quickly.

けれども、調査旅行の冒頭に経験した事は、その後に経験したものと比較すると、ほんの小さな出来事でした。博物館が面している湾には十数頭のイルカが泳いでいました。この調査の目的は、呼吸マスクと心拍数ロガーを使用して安静時代謝率を測定することでした。機材と明日の予定を決めたら、美味しい夕食を食べて、あっという間に安らかな眠りに落ちました。

The light-hearted mood lasted until the experiment. As an assistant of my mentor, my job was to observe and record details of the experiment setting, including but not limited to date, temperature, and start time, using whether pen or camera. Our research objects were two spotted dolphins called Rio and Lana. Everything seemed to be smooth at first. Dolphins were resting on the stretcher and the logger was attached properly. But when it came to the flow cup, Rio became reluctant and started to struggle. Although we managed to finish the experiment, Rio’s data was not that promising. Luckily, Lana was more cooperative and we had some valuable data.

お気楽な気分でいられたのは実験が始まるまででした。私の仕事は、メンターである青木先生のアシスタントとして、ペンやカメラを使って、日付、温度、開始時刻などの実験設定の詳細を観察し、記録することでした。私たちの研究対象は、リオとラナと呼ばれる2頭のマダライルカです。最初はすべてがスムーズに見えました。イルカは担架で休んでいて、ロガーをきちんと取り付けることができました。しかし、呼吸マスクをつけようとするとリオは嫌がり苦戦を強いられました。なんとか測定は終了しましたが、リオのデータはあまりうまくはとれませんでした。幸いなことに、もう一頭のラナは実験に協力的で、貴重なデータを得ることができました。

In the next day, we tried to remove the stretcher and let the trainers hold the dolphin as still as possible in the water. It did work well. It was a pity that I had to leave before the end of this research due to school affairs. Nevertheless, it was a valuable experience to me. It showed me the difficulties I might encounter in my future research, and most importantly the way to resolve them. No matter how well you prepare in advance, there would be always unforeseen circumstances and the research should be adjusted accordingly.

翌日、私たちは担架を外し、調教師に頼んで水中でイルカをできるだけ静止させようとしましたがうまくいきました。私自身は学事の都合で、この実験が終わる前に帰らなければならなかったのは残念でした。とはいえ、私にとっては貴重な体験でした。今後、研究を進めていく上で遭遇するであろういくつもの困難を経験し、それらをどうやって解決すればよいのかを知ることが出来ました。どんなに事前に準備をしていても、不測の事態は必ず発生するので、それに応じて調査を調整する必要があるということが分かりました。

On the way back to the housing, I noticed the painted tiles on the road with numerous cetacean species on them. Some were aged and weathered by the salty wind. Yet, the grass stretching out from the junction of tiles brought some liveness after all. It has always been good to go out.

家路の途中、太地町の道路のタイルに様々な鯨類が描かれているのに気づきました。いくつかは海風によって老化し、風化していました。それでも、タイルの接合部から伸びる雑草を見ていると、なぜだか元気が出てきました。コロナ禍でずっと外出が出来ませんでしたが、こうやって外出するのはやっぱり楽しいなあとおもった次第です。

Figure 3. The tiles painted with cetaceans in front of the museum

Figure 3. The tiles painted with cetaceans in front of the museum 図3 博物館前のタイルに描かれた鯨類たち

図3 博物館前のタイルに描かれた鯨類たち 2022年活動報告

-国内各所における野外調査を遂行-

2023年01月20日(金)

今年度、49件で総額816万8266円を寄付していただきました(2023年1月10日現在)。活動報告としてHP上にてお伝えしたとおり、昨年度から引き続きコロナ禍で様々な活動が滞りがちな中で、岩手県をはじめ、国内各所における野外調査を遂行することができました。皆様のサポートを受けて実施した野外調査の結果は、現在大学院生達がとりまとめ中です。今年度は計3名の修士課程修了者がいるため、2月上旬の発表会に向けて毎日夜遅くまで研究室は賑わっています。

2022年は計9本の原著論文を公表する事ができました。その中でも2018年3月に学位を取得し、現在名古屋大学で特任助教として活躍中の後藤佑介さんとの共同研究成果が5月にPNAS Nexusに公表されました。論文タイトルは“How did extinct giant birds and pterosaurs fly? A comprehensive modeling approach to evaluate soaring performance(絶滅した巨大鳥類と翼竜類はいかにして飛んでいたか?滑空能力を評価する包括的モデルによるアプローチ)”はYahooニュースをはじめとした国内外のマスメディアで大きな反響がありました。

また、昨年度本基金のサポートを受けていた木下千尋さんは、日本学術振興会特別研究員として名城大学に移籍しましたが、佐藤・木下による絵本「なぜ君たちはグルグル回るのか:海の動物たちの謎」が福音館書店より11月に出版されました。小学校高学年向けの内容ですが、大人からも大好評を博しています。絵本とバイオロギングカレンダーは、継続支援をして下さった方と3万円以上のご寄付をいただいた方へ年末にお送りしたところです。コロナ禍の収束がなかなか見えてこない状況ではありますが、来年度の各種野外調査を着実に遂行できるよう、今から準備を着々と進めています。

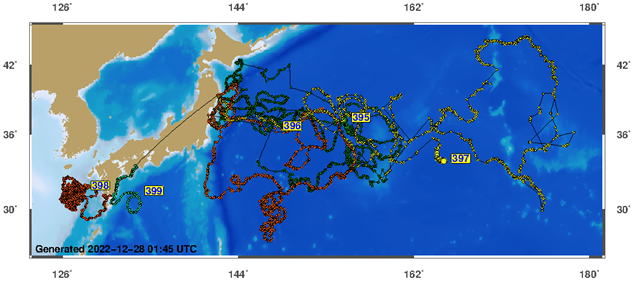

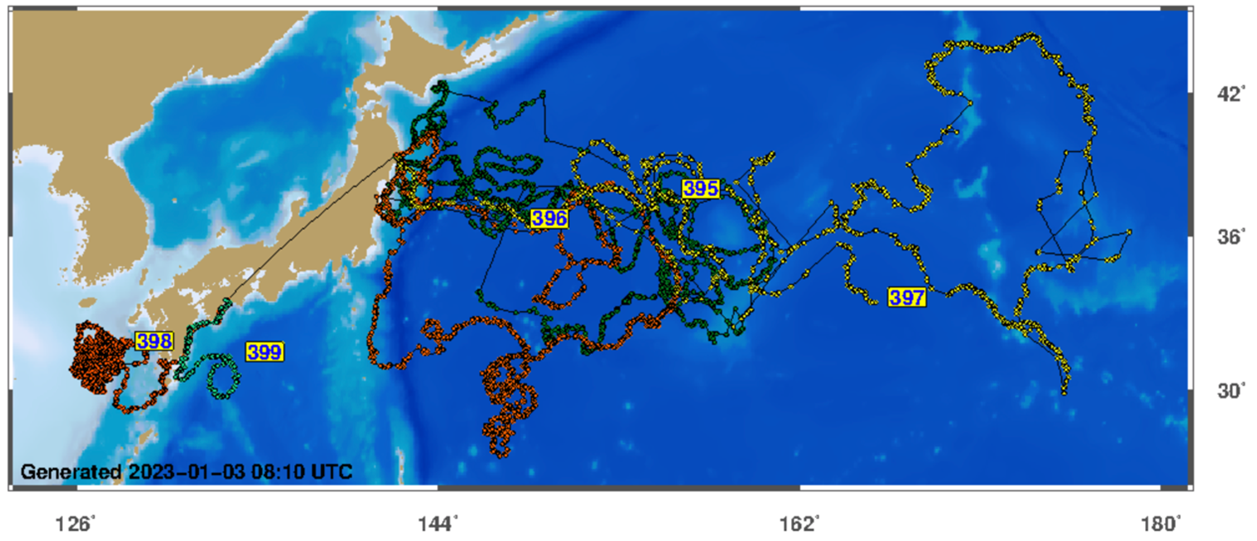

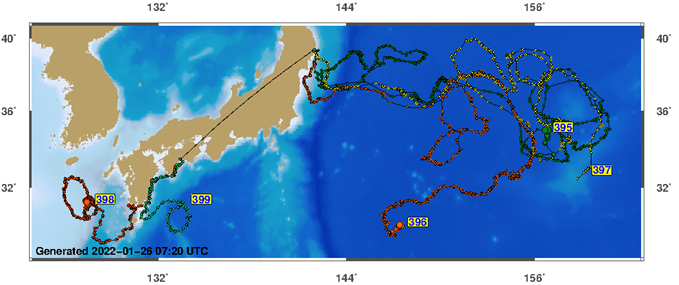

昨年度(2021年)の夏に人工衛星発信器をつけて放流したアカウミガメ5個体の内、2頭(396と399)は既に通信が途絶えていますが、岩手から放流した3頭の内2頭(395日本スピンドル2号と397)と、高知から放流した2頭の内1頭(398信ちゃん)はまだ受信が継続しています。装置の電池寿命は約1年なので、1年以上も長持ちしていることになります。

2022年の夏には岩手から3頭のアカウミガメに人工衛星発信器をつけて放流しました。内1頭(646)は放流直後に定置網に引っかかって死亡した模様で、通信が途絶えています。残る2頭は外洋に向かって泳いでいきました。1頭(644衣織ちゃん)は11月20日に最後の通信があった後、1ヶ月ほど途絶えています。電池寿命がなくなるにしては早すぎるのでもしかしたら良くないことが起こったのかもしれません。ただ、付着生物のせいなどで1〜2ヶ月通信が途絶えた後に再び復活することもありますので、もう少し経緯を見届けようと思います。もう1頭(645衣知花ちゃん)は通信が継続しています。電池寿命に達する2023年夏まで経路を追い続けたいところです。

■ご寄付の使途

いただいたご寄付は以下の目的のために、活用いたしました。

・バイオロギング装置回収用のVHF発信器

・ウミガメ装着用人工衛星電波発信器

・魚類装着用人工衛星電波発信器

・人工衛星電波受信料

温かいご支援を賜り、ありがとうございました。

ウミガメ達の今(&バイオロギングデータベースを作りました)

佐藤克文(東京大学大気海洋研究所・教授)

2023年01月05日(木)

昨年度(2021年)は人工衛星発信器をつけたアカウミガメ3頭(395, 396, 397)を岩手から、秋には高知から2頭(398, 399)を放流しました。岩手から放した396番は約1年後の2022年7月に東北沖で通信が途絶えました。発信器の電池寿命が約1年なので、おそらくバッテリー切れによる通信停止だと思われます。岩手から放流した残る2頭395番(日本スピンドル2号)と397番は、何と1年数ヶ月が経過した今でも(395: 2023年1月3日、397: 2022年12月30日)通信が継続しており、東北沖を自由に泳ぎ回っています。高知から放流した399番は、放流後間もない2021年11月に九州沖で通信が途絶えています。電池寿命にしては早すぎるので、おそらく漁業によって混獲されたなど、何か良くないことが起こったものと推察しています。高知から放流したもう1頭(398信ちゃん)は2022年12月19日に最後の受信があった後、しばらく通信が途絶えています。発信器に付着生物などがついたために一時的に通信が途絶えることは良くあることなので、もう少し様子を見たいところです。でも、この個体(398信ちゃん)は高知を出発した後、九州の西側の東シナ海に回遊し、そこで1年近く滞在しています。潜水行動の記録をみると、深度150mもの潜水をずっと繰り返しています。残念ながら何を食べているのかは分かりませんが、そこに長期間滞在して潜水を繰り返していることから、よほど美味しいもの、おそらく大陸棚上の底生動物を食べていたものと想像されます。

2022年の夏には3頭のアカウミガメ(644, 645, 646)に人工衛星発信器をつけて岩手から放流しました。内1頭(646)は放流直後に定置網に引っかかって死亡した模様で、通信が途絶えています。残る2頭は外洋に向かって泳いでいきました。1頭(644衣織ちゃん)は11月20日に最後の通信があった後、2ヶ月以上通信が途絶えています。電池寿命がなくなるにしては早すぎるのでもしかしたら良くないことが起こったのかもしれません。もう少し経緯を見届けようと思います。もう1頭(645衣知花ちゃん)は2022年12月27日に最後の通信がありました。電池寿命に達する2023年夏まで経路を追い続けたいところです。

今回は、これまで人工衛星をつけて放流したアカウミガメ8頭の経路について紹介しましたが、私達の研究室では、それ以外の種類のウミガメや、オオミズナギドリといった海鳥にも人工衛星発信器やGPSをつけて、位置データを取っています。日本バイオロギング研究会という組織があって、そこに所属する研究者は魚類・爬虫類・鳥類・哺乳類など、様々な動物のバイオロギング研究を進めています。貴重なデータをみんなで共有し、様々な目的に利用することを目指して、バイオロギングのデータベース、Biologging intelligent Platform、略してBiPを作りました(https://www.bip-earth.com)。誰でもそこに入って自分が気になる動物の回遊経路を眺めることが出来ます。ただ、現在は英語による表示が多く、研究者以外の人が使うにはあまり親切な設計になっていません。来年度はもっと分かり易い形に改造し、小学生にでも使えるようにしていきたいと思いますので、ご期待下さい。

経路の見方

1.トップページのViewDataボタンを押します。

2.Organism Speciesという欄には動物種の学名が記されています。例えばCalonectris leucomelasというのはオオミズナギドリという海鳥のこと。アカウミガメだったらCaretta carettaです。

3.表の右端のActionという欄の右端のマーク(Visualize location)を押してみると、その個体の経路を見る事が出来ます。

沖縄県黒島でウミガメの調査をしました!

2022年12月09日(金)

大気海洋研究所 行動生態計測分野 博士1年 河合 萌

沖縄県の八重山諸島にある黒島で、7月~9月の2カ月間ウミガメ調査を行いました。黒島は、人口約220人に対して牛が3000頭近くもいる、非常に自然が豊かな場所です。私たちは、NPO法人日本ウミガメ協議会が運営する黒島研究所との共同研究として、アオウミガメの野外での行動を明らかにするために、放流実験を行いました。アオウミガメ6頭にビデオカメラ、行動記録計、GPS記録計などを装着して、海へ放流しました(図1)。

ウミガメに取り付けたビデオカメラや記録計は、3~4日経過すると切り離し装置によって自動で海上に浮上します。浮上した機器類は、船やカヌーで探すことで無事回収することができました。ビデオ映像には、アオウミガメが海草を採餌している様子や他個体と遭遇している様子などが記録されていました(図2)。また不思議なことに、GPSデータを見ると、アオウミガメが捕獲された場所に対して島の反対側で放流をすると、再び捕獲した場所に戻る、という行動が見られました(図3)。数日以内になぜ元の場所へ戻るのか、どのようにして戻るのか、といった様々な疑問が出てきました。こうした疑問を解決できるよう、引き続き調査を続けていきたいと思います。

図4 装置を付けた後に放流した個体(日本スピンドル3号)の様子をドローンで撮影

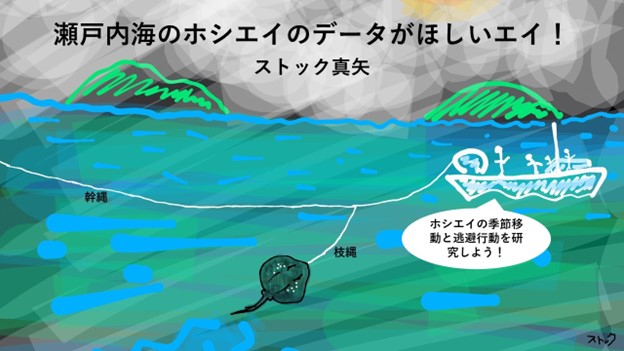

瀬戸内海のホシエイのデータがほしいエイ!

2022年10月31日(月)

Maya Stock (Master’s Student, Department of Natural Environmental Studies, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo)

マヤ・ストック(東京大学大学院新領域創成科学研究科自然環境学専攻・修士1年)

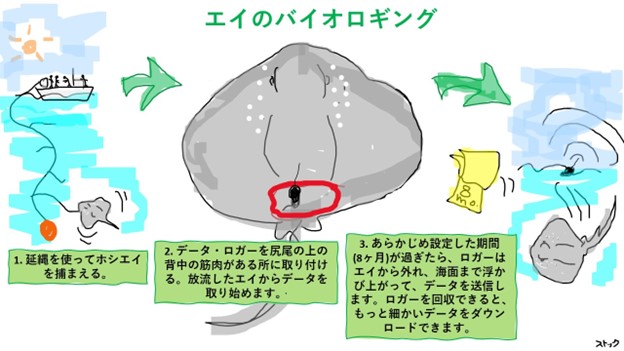

In the last week of September 2022, I headed to Kaminoseki to study pitted stingray (Bathytoshia brevicaudata) in the Seto Inland Sea. The goal for this trip was to attach MiniPAT tags to five rays, so that we can gain insights into their behavior and ecology in the region by collecting data such as location, temperature, depth, and 3-axis acceleration. We are specifically interested in how these rays might be moving seasonally, and where they go after longline capture and release. These are important questions, not only from an academic perspective, but also from a societal perspective, as these rays are known to take the fish caught by fishermen, and also damage nets. By conducting biologging research for this species, we hope to find ways to reduce the damage they are causing, while also learning more about the species’ swimming behavior and ecology. At the same time, we can also gain helpful experience on how to conduct biologging on these fish, since biologging on more coastal rays is currently still rather rare.

2022年9月の最終週、瀬戸内海のホシエイを研究するために山口県の上関に向かいました。今回の調査目的は、5匹のホシエイにMiniPATタグを付けて、位置・温度・深度・3軸加速度などのデータを収集することで、ホシエイの行動や生態を調べることでした。私たちは、エイが季節的にどのように移動するか、あるいは延縄により捕獲された個体が放流された後にどこに行くかに特に関心があります。ホシエイは漁師が獲った魚を捕らえたり、網を傷つけたりする被害が知られているため、今回の調査は学術的な観点だけでなく、社会的な観点からも重要です。バイオロギング研究を行うことで、ホシエイが引き起こしている被害を軽減する方法を見つけると同時に、ホシエイの遊泳行動や生態についてより多くのことを調べたいと考えています。同時に、沿岸性エイの生物学的記録は現在まだかなり稀であるため、調査手法の開発という意味においても貴重な経験となります。

Considering the relative rarity of literature on coastal stingray biologging techniques, I was uncertain about how well this field excursion would go. Furthermore, the only fishing experience I had prior to heading to Kaminoseki was one time many years ago at a summer camp in the U.S.A., where as a young girl I reeled in an unimpressively small trout—a very different experience from longline fishing for rays in the Seto Inland Sea. Thus, I was very nervous, and the excitement of my first visit to Kaminoseki did not sink in at first. However, once I started the final leg of the journey to Kaminoseki, I was able to get a good view of the Seto Inland Sea from the train window. Before coming to Japan as a research student this summer in preparation for beginning my master’s studies later in the fall, I had mostly grown up periodically visiting the West Coast of the U.S.A. with my family, where you can see the Pacific Ocean stretching out as far as the eye can see. The Seto Inland Sea, in comparison, felt much more sheltered and closed, with many small islands scattered throughout. “Do pitted stingrays stay mostly in the Seto Inland Sea, or do they move out to other areas—even the Pacific Ocean—depending on the season or if they are disturbed?” That was one of the many questions we had heading into the field study. From my train seat, as I clutched my hiking backpack and suitcase containing the five precious tags we hoped to deploy, I thought “We’re really, actually going to do ray research in the Seto Inland Sea”. As the reality finally began to hit me, my excitement and anticipation grew.

沿岸性エイの調査手法に関する文献が比較的少ないこともあり、私自身この野外調査がうまくいくかどうか今ひとつ自信がありませんでした。さらに、私が過去に経験した唯一の釣り体験は、だいぶ昔の幼少期にアメリカでのサマーキャンプで、ちっぽけなマスを釣り上げたくらいで、瀬戸内海で大きなエイを釣り上げるのは全く初めての体験でした。そのため、私は非常に緊張し、なかなか興奮が覚めませんでした。しかし、いよいよ上関が近づいてくると、車窓から瀬戸内海がよく見えました。この夏、研究生として来日し、秋から修士課程に入る準備をしていましたが、来日以前の私は家族と一緒にアメリカの西海岸を定期的に訪れていました。その時目にした太平洋に比べて、瀬戸内海は閉鎖されているように感じられ、多くの小さな島々が散らばっていました。「ホシエイは季節を通して主に瀬戸内海にとどまっているのか、それとも延縄にかかって放流された後は太平洋など他の海域に移動するのだろうか?」これは、フィールド調査に臨む私たちが抱いていた疑問でした。大切な5つのタグ(MiniPAT)が入ったリュックとスーツケースを手に電車の座席から立ち上がった時、「本当に瀬戸内海でエイの研究をするんだな」という実感が湧いてきて、私の興奮と期待は最大となりました。

After arriving in Kaminoseki in the evening of September 25th, we headed out in the morning of September 26th from Shirahama Port to put out the first longline. I was looking down a lot of the time while putting bait on the hooks, but still was able to take in the scenery of the coastline, emerald water, and islands in the distance. Once we returned to port, we waited for some hours, and then went out to sea again to check on the longline we had previously set. Unfortunately, the rays had evaded us this time, so we set out a fresh longline and then headed back to port.

9月25日夕方に上関に到着し、9月26日朝、白浜港から延縄を積んだ船で出港しました。私は釣り針に餌を付けながら下を向いていることが多かったのですが、それでも海岸線やエメラルド色の海、遠くに浮かぶ島々の景色を眺めることができました。港に戻って数時間後に、再び海に出て、設置した延縄を確認しました。残念ながらホシエイはかからなかったったので、新たに延縄を設置して帰港しました。

After another period of waiting, we headed out to sea once again, where we found that we had finally caught a pitted stingray. A buoy was first attached to the line leading to the fish so that we could keep track of where it was prior to deploying the tag. I could see the buoy bobbing up and down furiously, and almost being pulled under water. Although I could not yet see the actual ray, I thought that it must be extremely strong and large to be able to pull the large buoy with such force. Once the ray was brought to the surface, this guess was confirmed. It was a female pitted stingray measuring 156 cm across, and with tiny white spots like many stars on its back, just like its Japanese name suggests. We successfully attached a tag to the muscular region near the tail, where we hoped to avoid the vital organs and minimize negative impacts on the fish. After releasing the ray, we once again set out a longline and then returned to port. When we checked in the evening, we found a smaller male ray, which we also put a tag on and released. We then set out another longline, which we planned to keep in the water overnight, and then check in the morning.

しばらく待って再び海に出てみると、ようやくホシエイが釣れました。タグを装着する前に、まず幹縄からエイのついた枝縄を外し、エイを追跡できるように枝縄にブイを取り付けて放しました。ブイが猛烈に上下に揺れ、水中に引きずり込まれそうになっているのが見えました。まだエイの実物を見ることはできませんでしたが、これだけの力で大きなブイを引っ張れるのは、とても強くて大きいエイに違いないと思いました。エイが海表面に近づくと、この推測が当たっていたことがわかりました。体長156cmのホシエイのメスで、その名の通り背中に星のような小さな白い斑点がたくさんあります。内蔵を傷つけることによる魚への悪影響が無いように、尾の近くの筋肉組織に銛を打ち込み、タグを曳航させることに成功しました。エイを放した後、再び延縄を仕掛けてから帰港しました。夕方延縄を確認したところ、小さめのオスのホシエイが捕れたので、こちらもタグを付けて放流しました。それから、翌朝にチェックする予定の延縄を設置しました。

The morning of September 27th was stormy, so we waited indoors as the rain hammered down, hoping that after the storm passed, we would find more rays. We finally were able to head out around noon, and found three rays (two males and a female), all of which we attached tags to and released. Thus, we were able to successfully deploy all five of the tags we brought.

9月27日の朝は天気が悪く、ホシエイが取れることを願いつつ屋内で待ちました。お昼頃にようやく出航でき、ホシエイを3尾(オス2尾、メス1尾)捕まえられたので、タグを付けて放流しました。このように、持ってきた 5 つのタグすべてを装着することができました。

For the deployed tags, we are still eagerly waiting in anticipation for the arrival of information in hopefully about 8 months, when they are programmed to detach from the rays, float to the surface, and transmit collected data to us. If we are lucky, and can track down and actually retrieve the tags, we will be able to access more detailed data as well. Speaking of luck, we had both lucky and unlucky events happen shortly after deploying the five tags. The unlucky part was that we learned about a week after deployment that one of them had prematurely detached from its host ray and was drifting about in the Seto Inland Sea, and the lucky part was that we were able to retrieve it. After carefully watching the map tracking the path of the detached tag and considering the local fishermen collaborators’ expert advice regarding sea conditions, we hurriedly departed port from Kaminoseki several days later at around 2:00 when the sea conditions were supposed to be favorable, and used a Goniometer (a direction finder that detected signals from the tag and pointed us in that direction) to search the dark predawn waves for the tag. I mainly checked the Goniometer (my assigned role) and was nervous (not my assigned role), and thus was mostly staring at the direction finder screen’s arrow pointing us in the right direction. The actual spotting of the tag once the sun came up was done by the local fisherman collaborator who was part of the search party. He spotted the tag floating in the middle of some floating debris. Thanks to his and everyone else’s efforts, we fished the tag out of the water with a net and triumphantly headed back, arriving in port at about 6:00. Our approximately four-hour search was fruitful, as the data logger, when plugged into a laptop, was seen to contain recorded data, which we will be analyzing. Meanwhile, back out at sea, we hope that the other four data loggers are busily collecting information on the lives of their rays, so that we will be able to gather more long-term data.

装着されたタグは約8か月後にエイから切り離されるようプログラムされており、人工衛星経由で情報が得られる予定です。運良く脱落したタグを回収できれば、より詳細なデータも得られます。運といえば、5つのタグを装着してエイを放流した直後に、幸運と不運の両方のイベントが発生しました。運が悪い方のイベントとは、放流から約1週間後に、5尾うちの1尾からタグが切り離されてしまったということです。外れてしまったタグが瀬戸内海を漂流する軌跡を地図で確認しつつ、地元の漁師協力者の海況に関するアドバイスを考慮した後、海況が良くなると期待される日の2:00頃に上関を出港し、ゴニオメーター(タグからの信号を検出し、その方向を示す方向探知機)を使って夜明け前の暗い波間に漂うタグを探索します。私は主にゴニオメーターのチェックを担当し、緊張の時間を過ごしつつ、タグの方向を指し示す方向探知機画面の矢印を見つめていました。日が昇った後、捜索隊の一員であった地元の漁師が海面を漂う海ゴミの真ん中にタグが浮いているのを見つけました。みんなの努力の甲斐あって私たちは網でタグを水からすくい上げ、意気揚々と6:00頃に港に到着しました。タグをPCに接続すると、無事にデータが記録されていることがわかりました。私は現在そのデータを解析しています。その他4つのタグは、今も海でホシエイの生活に関する情報を記録してくれているはずで、より長期的なデータを収集できることを願っています。

Finally, although the majority of the data we hope to gather are yet to arrive, I have been able to make a couple of other preliminary conclusions from my first trips to Kaminoseki. First, fishing for rays in the Seto Inland Sea is indeed—unsurprisingly—very different from fishing for trout in a pond. The former is more challenging, but also much more intriguing, than the latter. Second, and more importantly, I am very fortunate to be able to conduct this interesting research, and as part of a team with many kind and knowledgeable people. I would like to extend a special thank you to all of the researchers and fishermen who are a part of this endeavor.

最後に、取りたいデータの大部分はまだ得られていませんが、上関で行った最初の調査旅行から、いくつかの予備的な結論を出すことができました。まず、瀬戸内海でのホシエイ釣りは、当然のことながら、池でのマス釣りとは大きく異なります。前者は後者よりも挑戦的で、はるかに興味をそそられます。第二に、そしてもっと重要なことに、私はこの興味深い研究を行うことができて、そして多くの親切で知識豊富な人々とのチームの一員になることができて非常に幸運です。この困難な試みに共に挑んでくれたすべての研究者と漁師に特別な感謝の意を表したいと思います。

2022年 バイオロギングの絵本出版

佐藤克文(東京大学大気海洋研究所・教授)

2022年10月14日(金)

唐突ですがバイオロギングの絵本が出版されました。私がストーリーと文章を担当し、私の研究室で学位を取得し、現在博士研究員であると同時にイラストレーターとしても大活躍中の木下千尋さんが絵を描きました。

小学生高学年を対象とした絵本ですが、これまでに公表した学術論文5本分くらいの高度な研究成果をかみ砕いて紹介しています。研究成果もさることながら、私達が伝えたかったのは研究する過程です。絵本では老教授となった私が大学院生と一緒にフィールドに出向いたりして、楽しそうに調査や研究を進めています。そこに描かれている逸話は、実際に大学院生達が経験した実話です。

巻末の「作者のことば」も気合いを入れて書きました。毎年多くの大学生が大学院進学を念頭に研究室見学にやってきますが、そんな人達に是非伝えたいことを記しました。

詳しくはこちら

今年度に入り、既に何人もの方からご寄付をいただいております。誠に有り難うございます。毎年1万円以上の継続的なご支援をして下さっている方、および一括3万円以上のご寄付を下さった方には特製カレンダーをお送りしていますが、今年はこの絵本もあわせてお送りします。是非ともご支援をお願いいたします。

2022年ウミガメ調査開始

2022年07月06日(水)

暑い夏が続きますが、皆さん如何お過ごしでしょうか。2005年から継続して行ってきた岩手県大槌町周辺海域におけるウミガメ調査がまた今年も始まりました。7月1日に大槌入りしてまず最初に驚いたのは涼しさです。我々が普段暮らす柏市では連日30℃台後半だったのですが、こちらは25℃前後です。日差しは強いのですが、日陰に入っていると何とも心地よい風が吹いています。

最初に地元の関係者に挨拶に行きました。混獲されるウミガメを港まで持ってきてくださる定置網漁業者の皆様、我々が取りに行くまで水槽に入れておいといてくださる魚市場の方々に今シーズンも協力をお願いし、快諾していただけました。そして7月5日に早速アカウミガメが1頭捕獲されました。いつものように体サイズ測定や標識装着などを行ってから水槽に運び入れました。

昨年放流した5頭のウミガメの現時点までの回遊経路を以下に示します。高知県で放流した399番は、理由不明のまま2021年11月20日に通信が途絶えています。しかし、残る4頭はまだ回遊を続けています。高知県から放流したもう1頭の398番は東シナ海がお気に入りとみえて、ずっと同じ場所に留まりながら深度50〜100mの潜水を繰り返しています。岩手から放流した3頭は、未だに沿岸から沖合をフラフラと泳ぎ回っています。397番は、アカウミガメとしては過去最高記録に近い深度440mの潜水を1回行っていました。水温6℃にもなるそんな深いところでいったい何をしていたのでしょうか。

今年度に入り、既に何人もの方からご寄付をいただいております。誠に有り難うございます。寄付のシステムが昨年度から変更され、グッズや御礼状の送付が滞っておりますが、今しばらくお待ちください。

コロナの影響がウミガメに?!

2022年03月03日(木)

当研究室で学位を取得し、現在東京農工大学の博士研究員である福岡拓也さんが、昨年夏に岩手県大槌町の東京大学大気海洋研究所国際沿岸研究センターにおいて、アオウミガメの糞からマスクが発見されたことを論文にして公表してくれました。

東京農工大学と東京大学大気海洋研究所からプレスリリースがなされました。

・新型コロナウイルス感染拡大に由来するとみられるプラスチックゴミをウミガメが摂食していることを確認しました。

https://www.tuat.ac.jp/outline/disclosure/pressrelease/2021/20220210_01.html(東京農工大学)

https://www.aori.u-tokyo.ac.jp/research/news/2022/20220210.html(東京大学大気海洋研究所)

論文内容は各種新聞紙面で紹介されたほかに、テレビのニュース番組でも取り上げられています。

・ポイ捨てマスクの“誤飲”増加 散歩中の犬やウミガメにも…

https://news.ntv.co.jp/category/society/0e3da31ef43e42b28654a7f9ca060df5

2021年活動報告

-ウミガメやクジラ、ウミドリ、カジキ等の生態調査を進めています!-

2022年01月28日(金)

今年度、42件で総額388万7千円を寄付していただきました。活動報告として毎月HP上にてお伝えしたとおり、昨年度から引き続きコロナ禍で様々な活動が滞りがちな中で、岩手県をはじめ、国内各所における野外調査を遂行することができました。

海外においても、研究室から旅立っていった博士研究員の後藤佑介さんがフランス留学中にインド洋に浮かぶエウロパ島へ赴き、グンカンドリの調査を行うことができました。皆様のサポートを受けて実施した野外調査の結果は、現在大学院生達がとりまとめ中です。今年度は計8名もの修士課程修了者がいるため、現在2月上旬の発表会に向けて毎日夜遅くまで研究室は賑わっています。他にも、今年度は2名が博士号を取得予定です。

2021年は計15本の原著論文を公表する事ができました。その中でも2021年3月に研究室を旅立ち、4月に名城大学に助教として着任した楢崎友子さんが5月にiScienceに公表した論文 “Similar circling movements observed across marine megafauna taxa(複数の海洋大型動物にみられた共通の旋回行動)”は国内外で大きな反響がありました。本基金のサポートを受けている特任研究員の木下千尋さんは、論文をイラストで紹介する海洋生物研究者として、2021年6月15日付けの朝日新聞朝刊「ひと」欄で紹介されました。

バイオロギングカレンダーは、継続支援をして下さった方と3万円以上のご寄付をいただいた方へ年末にお送りしたところです。コロナ禍の収束がなかなか見えてこない状況ではありますが、来年度の各種野外調査も着実に実行できるよう、今から準備を着々と進めています。

上の画像は昨年夏に人工衛星発信器をつけて岩手から放流した3頭と、高知から放流した2頭の回遊経路です。ご支援をいただいた方に「日本スピンドル2号」と命名していただいた395番の個体と、「所さん」と名付けた396番の個体を含む岩手発の3頭は太平洋を優雅に航海しています。高知から放流した2頭のうち、399番の個体は理由はわからないのですが、2021年11月20日を最後に通信が途絶えています。もう一頭の398番は東シナ海で深度150mの潜水を繰り返しています。

インド洋のエウロパ島で行ったグンカンドリ調査

2022年01月05日(水)

私は佐藤研究室で学位を取り、現在フランスでポスドクをしています。今回は日本とフランスの共同研究で、2021年9月から10月下旬までグンカンドリという鳥の調査に行ってきました。場所はマダカスカル島とアフリカ大陸の間にあるエウロパ島です。大きさは直径約6km、周囲をサンゴ礁に囲まれています。本土からは離れていますがフランス領です。島に住んでいる人間は島の警備を行うフランス陸軍15名、自然保護員2名、そして島に45日間短期滞在する私と共同研究者のシャーリー・ボスト(フランス国立科学研究センター)さんだけです。この島は有数のアオウミガメの産卵地、また今回の調査対象であるオオグンカンドリの一大繁殖地として知られています。